_

Click to launch the photo gallery_

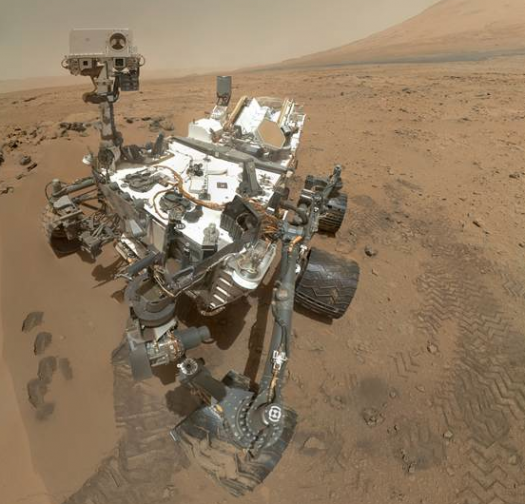

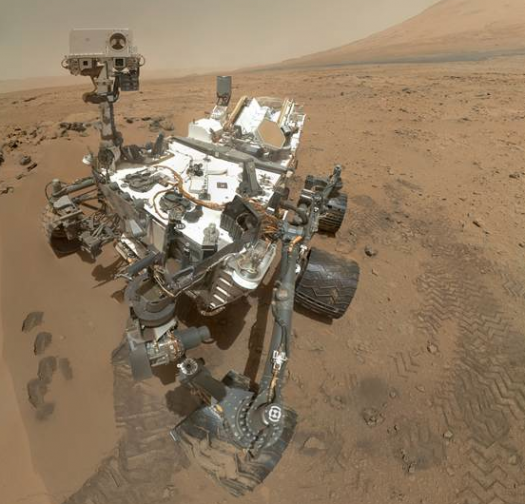

We are bidding farewell to an epic year for space explorers, who for the past 12 months have been graced with some of the best images and best science ever to come down from another planet. With no slight to Cassini, Voyager or the others, which are also still sending many happy returns, 2012 was all about Mars.

Many of you were glued to your livestreams and Twitter feeds in August–and through the onset of winter–for the touchdown and first rolls of the Mars rover Curiosity. Its intrepid sibling, Opportunity, also made some crazy new finds this year. There is a lot more to come in 2013, of course. But click through our gallery to see some of the best highlights from the Year In Mars.