Over the past few decades, researchers have spent a lot of time discovering the genetic roots of a number of conditions. Some of these diseases, such as Huntington’s, sickle cell, and cystic fibrosis, are controlled by a single gene. These are called Mendelian diseases. If a patient has a certain mutation on that one gene, it’s always been considered a guarantee that he will have the disease in question, and though treatment can often lengthen a patient’s lifespan, it can’t cure the disease.

In a new study, researchers discovered a handful of individuals who had the mutation but didn’t display signs of the disease. Understanding what makes them different might help researchers better treat or even prevent these conditions. The researchers published their study today in Nature Biotechnology.

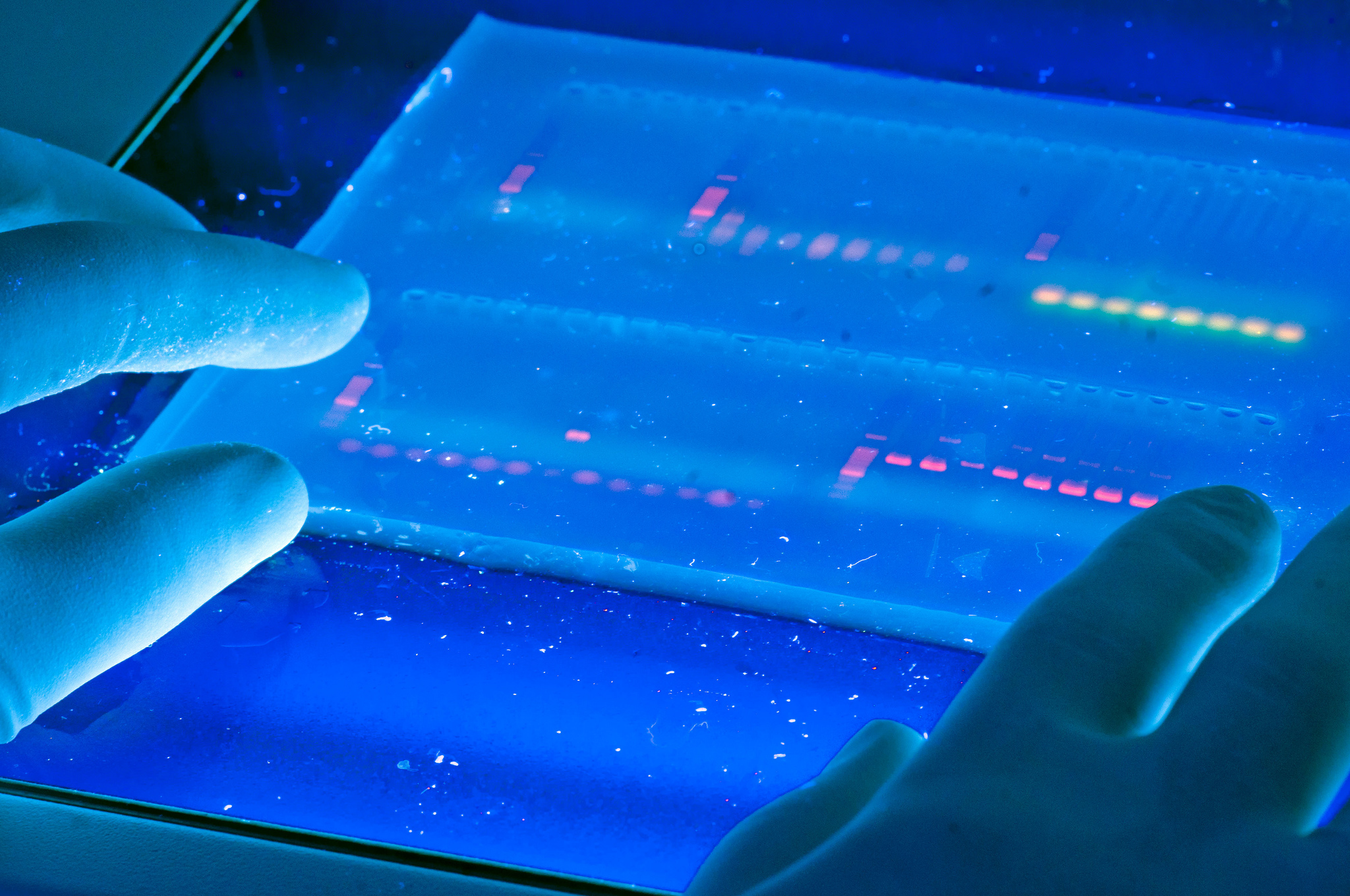

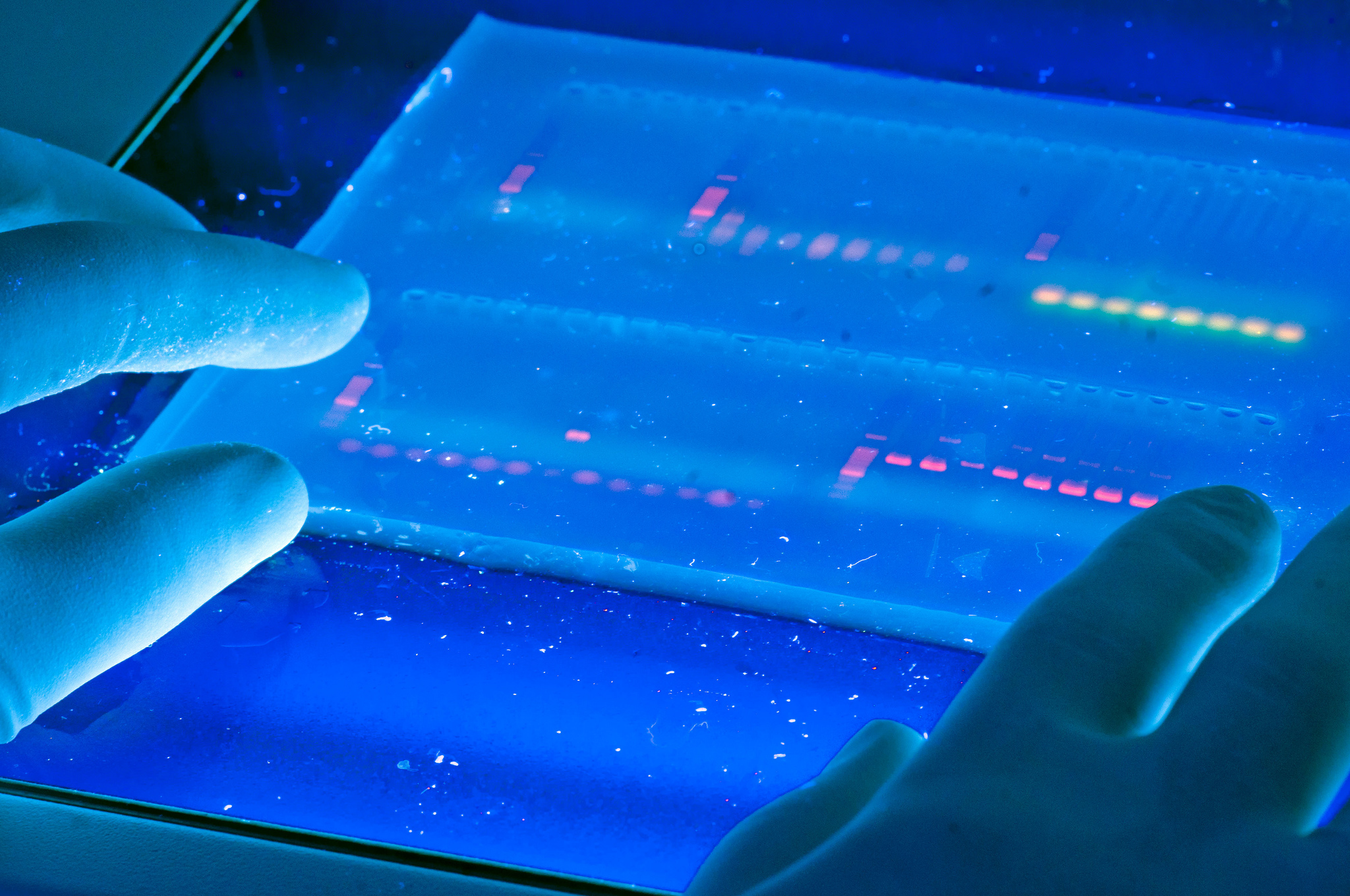

In the study, the researchers analyzed the genetic data from 589,306 patients from all over the world (about 68 percent of those records were supplied by personal genomics company 23andMe). They looked at 874 genes to look for 584 Mendelian conditions that set in during a patient’s childhood, and compared that data to information about the patient’s health. Out of these half a million patients, the researchers discovered 13 individuals that contained a mutation that would typically indicate a Mendelian disorder, but didn’t show any signs of disease.

Understanding what makes those individuals different might lead to better treatments or even a cure.

“This work that we started a few years ago was based on the idea that if you want to find clues to prevention, what you should do is instead of looking at people who are with disease, you would want to look at people who should have gotten sick,” Stephen Friend, the senior author of the study and the president of Sage Bionetworks in Seattle said in a press conference.

The analysis into the 13 individuals was limited, and so far there’s nothing apparent that they have in common. The researchers would need data on patient’s entire genomes to start to understand that, and the researchers couldn’t contact any of these individuals because of the agreement in their initial consent form.

“The purpose of the study was to see if the technology is ready, if it’s something worth directing efforts towards. The answer is yes,” Friend added.

Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine in New York, who also collaborated on the research, plan to do another study. Researchers looking for those rare protected individuals might target families in which several family members express a Mendelian disease, but a few do not.

Identifying the differences in their genes might help researchers someday find a way to cure them. “Most of the public probably thinks that mutations are bad or a risk,” said Friend. “There’s evidence here that changes how we think of what we carry in ourselves.”