For most of human history, cosmic events weren’t understood to be the simple result of physics—instead, they were messages from the divine or omens regarding the future. This is especially true for a total solar eclipse, where the moon entirely obscures the sun, bringing nighttime for a few bizarre minutes during the day.

An event as unmissable and odd as a total solar eclipse was, quite reasonably, something our ancestors considered worthy of recording. The earliest recorded solar eclipse took place in 1223 BCE, etched into an ancient Mesopotamian clay tablet. In the millennia since that initial recording, cultures across the globe have documented and interpreted solar eclipses in many different ways—and those historical records are even helping solar scientists better understand the sun in the modern age.

Nowadays, we understand a solar eclipse as the coincidental (but predictable) alignment of the Earth, moon, and sun, such that the moon blocks out the sun as seen from our perspective. Although other planets quite likely experience partial eclipses, our moon is uniquely situated such that its apparent size precisely matches up to that of the sun, fully blocking out its bright light.

Some of the oldest eclipse records are found in literature, such as the History of the Peloponnesian War by ancient Greek scholar Thucydides: “In first days of the next summer there was an eclipse of the sun at the time of new moon.” Petroglyphs in Ireland and the American Southwest also hint at long ago eclipse observations, with spirals and other symbols corresponding to the Earth, moon, and Sun in their celestial dance. Some ancient Chinese records also describe when “the sun has been eaten”—even including a gruesome note that two of the emperor’s advisors were killed for failing to successfully predict the eclipse. An ancient Hindu text called the Rig Veda told how the sun disappeared around 4000 BCE, until it was liberated by the religious figure Rishi Atri.

Although some texts weren’t written until many years after an eclipse actually occurred, “astronomical stories generally sustain well in people’s memory because the sky repeats itself every year, even if events like eclipses are rare,” explains University of Mumbai astronomer Mayank Vahia. “We have seen this in stories of tribes in India who can remember events that were 3000 years old, woven into a nice mythical story about Ursa Major.”

Eclipses could represent misfortune or a great destiny, depending on who you ask. Kings and emperors from nations like ancient Mesopotamia often saw an eclipse as a sure sign of their downfall. King Henry I solidified the European superstition of ill omen eclipses, as he died shortly after an eclipse and rumors spread wildly after that coincidence, but some major civilizations like the Aztec didn’t seem to care much at all. Indigenous people of North America had quite different perspectives on eclipses, too; the Southern Paiute saw the eclipse as a time for reflection, love, and giving, while others like the Ho-Chunk and Crow treat them as a time for new beginnings.

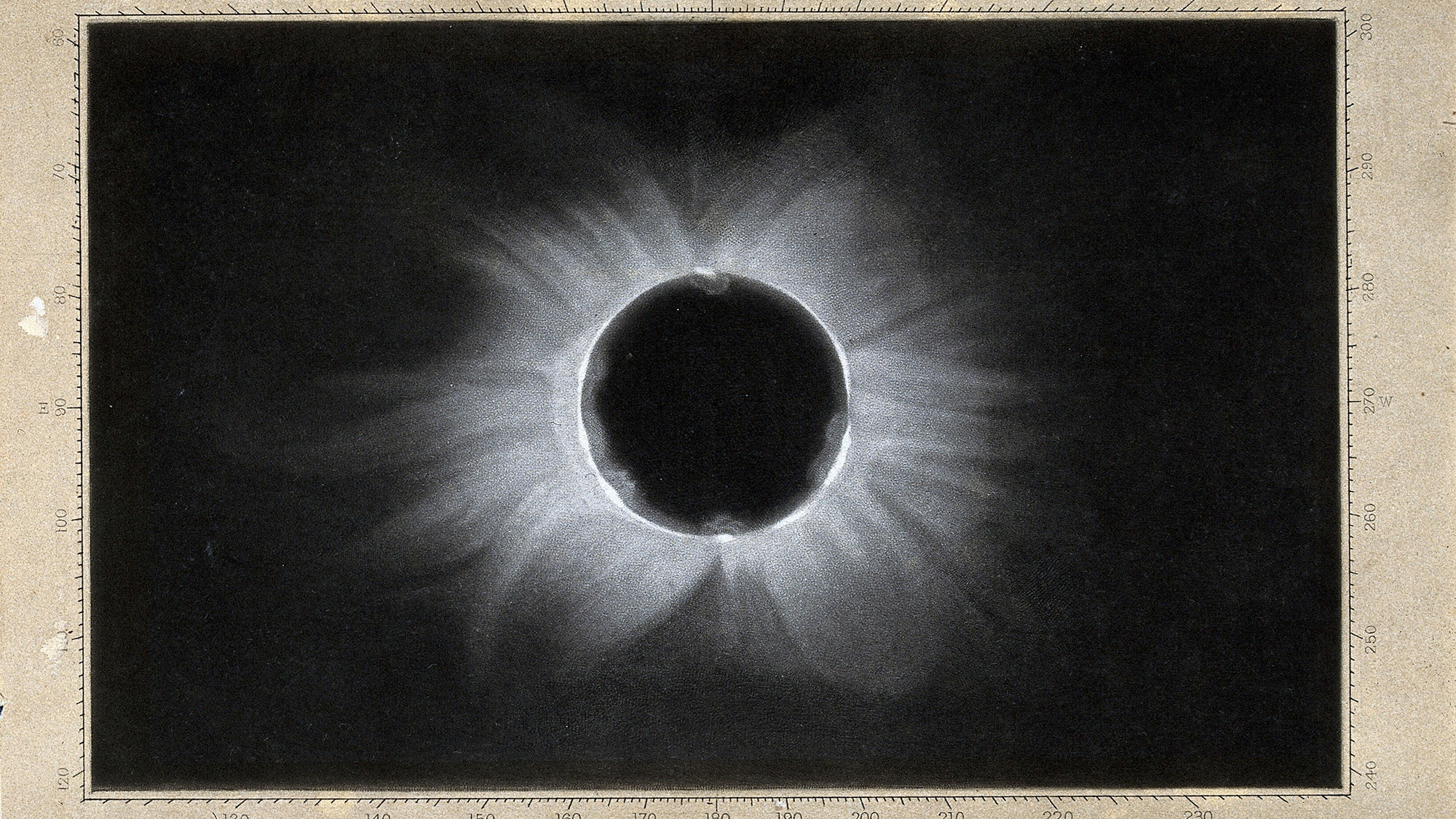

Around the 1600s, solar science as we know it today came into being. Famous astronomer Johannes Kepler suggested the corona—a ring of filaments and tenuous light that becomes visible around the sun during an eclipse—was actually a part of the sun, which we now know to be true. In the 1800s, people took the first photographs of a solar eclipse, and today people across the globe take selfies as an eclipse sweeps through their part of the world.

The history of eclipses not only connects us with humans across time—sharing that sense of wonder at our place in the cosmos—but also sheds light on the subtle motions in our solar system. For example, eclipse records suggest that Earth rotates at just about the same rate as it did 3,000 years ago and allow us to track changes in the planet’s motions. “The movement of the earth is gradually slowing down but occasionally there are sudden changes due to geological events,” adds Vahia. “Records of ancient eclipses, especially Solar Eclipses, are important in providing high-quality data to validate our calculations.” Plus, eclipses have been responsible for some major scientific breakthroughs, like the discovery of the element helium and tests of Einstein’s famous general relativity theory.

If you missed the most recent total solar eclipse earlier in 2024, the next total solar eclipse for the continental U.S isn’t until 2045—but you can see one before then if you’re willing to do a bit of travel. Whenever you get a chance, it’s worth it to witness a cosmic event so rare and weird that our ancestors have been talking about it for thousands of years.