Aiming laser light at the portion of the brain associated with impulse control could ease cocaine addiction, according to a new study in rats.

“When we turn on a laser light in the prelimbic region of the prefrontal cortex, the compulsive cocaine seeking is gone,” researcher Antonello Bonci says in a press release.

It may sound strange–and many experimental treatments that have worked in mice and rats don’t work in humans–but scientists are working on the critical next step to find whether this could work for people, too.

Previous research had suggested that that problems in the prefrontal cortex are linked to compulsive drug use, but hadn’t demonstrated that they caused drug addiction.

In the new study, researchers from institutions in Maryland and California offered rats levers that, when pressed, would give them infusions of cocaine. After more than eight weeks of the free coke, however, the researchers starting giving the rats a shock in the foot alongside the drug. For some rats, the shock made them reduce their lever-pressing. Others soldiered on, however, in spite of the consequences.

The researchers found that prelimbic cortex neurons in the consequences-be-damned rats were less responsive than the corresponding neurons in shock-fearing rats and in rats who had never had cocaine. The cocaine-taking, shock-fearing rats had some impairments, too, but not as much. These findings showed that cocaine use caused reduced responsiveness in the prelimbic cortex, the researchers wrote in a paper published today in the journal Nature.

The researchers then began stimulating shock-resistant rats’ brains with laser light. (Brain cells don’t normally fire in response to lasers, but researchers genetically engineered these rats’ brains to do so.) The laser treatment reduced how often the rats pressed their cocaine levers.

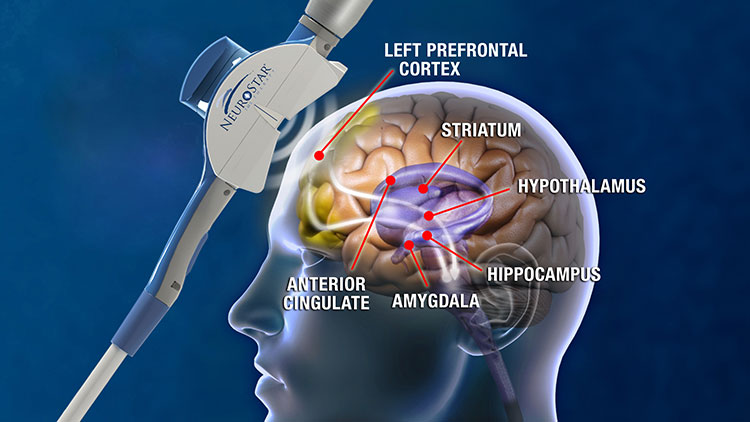

The same research team is now planning a clinical trial on humans, using a related technique. A search of the National Institutes of Health’s ClinicalTrials.gov database reveals that it is one of two apparently active, mid- and early-stage clinical trials of the related technique, called transcranial magnetic stimulation, for cocaine craving and dependence.

Doctors cannot aim lasers in human patients’ brains–nor can they genetically engineer us to respond to lasers–so transcranial magnetic stimulation works on the brain using tools placed outside of the scalp that stimulate activity in the prelimbic region of the prefrontal cortex. Transcranial magnetic stimulation currently used as a treatment for depression that doesn’t respond to drugs or therapy, according to the Mayo Clinic.