I learned how to cook the day I opened my first issue of Cook’s Illustrated. Phrases like Maillard reaction and gluten development and Best Blueberry Pancakes flowed across pages adorned with desaturated sketches, drawing me in with their simplicity and forthrightness. This is the best way to grill salmon or make pie crust, the articles said–and here are three pages of reasons why.

CI brought the scientific method to cooking: Take a hypothesis, test it, see if it comes out like you expect, and learn from it, improving your method next time. If a recipe doesn’t work, adjust it. And don’t worry about buying artisan bread and hand-cutting your hydrangeas to fit individual bud vases–that’s pretentious. Compared to other glossy food magazines, this was a revelation.

This excellent, recent New York Times profile of editor Christopher Kimball–a must-read for CI fans–will give any reader some insight into their methods. For most Americans, cooking is not about art, but about dinner, Kimball firmly believes. Sustenance. Success is often hard-won, dependent on, yes, some flair and some skill, but also on some basic knowledge of what heat and force can do to edible things. Now Kimball and his staff have distilled 50 of these basic rules into a new cookbook, “The Science of Good Cooking.” I think this is a great idea. Like knowledge of baking ratios, understanding the science behind cooking will free you from following recipes and allow you to be creative.

To be clear, Modernist Cuisine it is not–this book contains several very basic concepts and no liquid nitrogen. But if, like me, you are curious about chemistry and protein denaturation but have no idea how to achieve whirled peas, you’ll enjoy it.

To test its kitchen utility, I made three things that I already make (occasionally using variations on existing CI methodology), but I made them according to this new cookbook’s strictures, keeping their intended lessons in mind. Here’s how they turned out.

Scrambled Eggs

Lesson: Fat Keeps Denatured Proteins Together

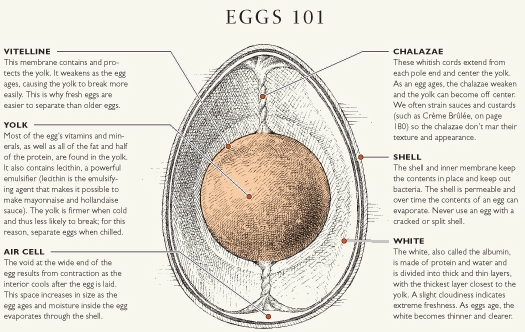

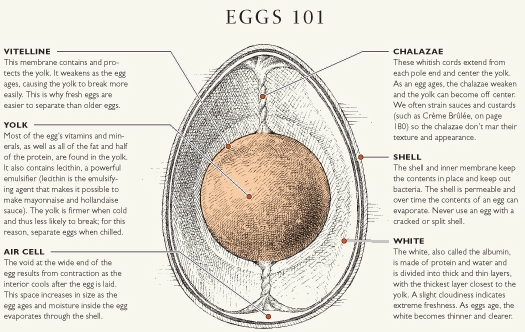

Scrambled eggs are arguably one of the easiest things to truly cook, if you use that definition to mean changing the structure of a food. You can scramble eggs in the microwave! (But you shouldn’t.) Yet there is a technique behind truly great scrambled eggs.

The America’s Test Kitchen method: Along with gentle beating and pre-salting, use extra fat. The book recommends adding an extra yolk, which adds an extra helping of lipids to your mixture. Then add half and half, not milk, for the same reason–the fat in the milk coats the proteins in the egg white and yolk, preventing the loss of too much liquid and yielding light, fluffy eggs. Also, cooking over low heat is key.

To make one serving, I beat two large eggs plus one yolk with a tablespoon of half and half, and a pinch of salt and pepper. I melted a quarter tablespoon of butter in a medium-high skillet and added the eggs, swirling them in the pan for about 90 seconds.

Did it work?

The eggs were tender and silken, a lovely goldenrod mass glistening with butter. It looked and tasted great–but it was ultimately too heavy for my taste. I think of scrambled eggs as a fairly healthy breakfast, but this adulteration made it seem like a sin, like it coated my insides for a day. I don’t think I would add the extra yolk again. But the half and half … probably.

Banana Bread

Lesson: Minimize Gluten And Up the Banana Flavor

Quick breads like banana bread and muffins are supposed to be tender and cakey but not chewy, which requires minimizing the development of gluten. Fats and sugars prevent gluten formation by interfering with protein folding. But you create it when you mix the batter, a necessary step to combine wet and dry ingredients. As the book puts it, it’s more what you don’t do that matters.

Even with a gentle touch, though, banana bread can be way too dense, a function of the relatively large amount of bananas you need to achieve great banana-y flavor. I usually smash bananas with a fork, stir them with the eggs and fat, and then add them to the dry ingredients. ATK has you do far more work–you have to microwave the bananas so they release their liquid, strain them for 15 minutes, then reduce the liquid in a saucepan until you have 1/4 cup of super-concentrated banana juice. This is added to the banana pulp, melted butter, brown sugar and eggs, keeping the liquid ratio correct, then it’s mashed with a potato masher.

Did it work?

Yes! This was far better banana bread than my usual, which includes some vegetable oil and white sugar instead of only butter and brown sugar. That alone was an improvement. But zapping the bananas in the microwave, something I would never have thought to do, yielded a dramatic difference. The loaf had more banana flavor, yet it wasn’t dense; it was still cake-like and fluffy. I would definitely make this again.

Flank Steak

Lesson: Give All Meat a Rest

A lean, thin slab of flank steak is supposedly one of the humbler cuts of beef, lacking the marbling and texture of a strip or any number of more expensive cuts. But it can still be juicy and tender when handled properly. I almost always marinate a flank steak, which improves it in two ways: Marinades inject their own flavors, and salting the meat (and the marinade) changes the muscle proteins, tenderizing them and drawing out moisture.

The recipe I wanted to test called for no marinade at all, no scoring and no brining. The entire success of the dish relied upon a lengthy rest once it came off the grill. I used cumin, chili powder, coriander, red pepper flakes, salt and pepper and a secret ingredient–cinnamon–and rubbed it all over the 2-lb steak. I preheated the grill for 15 minutes, like the recipe said, and threw the steak on for five minutes on one side, and three on the other. Then I brought it inside and ignored it for 10 minutes before slicing against the grain.

Did it work?

I think my grill was too hot, and the steak cooked more quickly than it should have–the edges were too dry after a short cooking time. But the center was still a dark pink, and the crust was delicious. I’d probably make it again, if only because I usually forget to marinate steak and don’t feel like waiting–and this is a very tasty, easy alternative.

Bottom Line: Trust Science

I’m clearly a fan of Cook’s Illustrated, so perhaps you should take all of the above with a fat grain of kosher salt. But forget about your favorite cooking style or celebrity chefs or foodie fads, and we can agree that cooking really is a science, with predictable outcomes based on initial conditions. Understanding the rules underlying those outcomes–which this book does very well–will make you a better cook.