Popular Science’s series, The Builders, takes you behind the construction tape to reveal the individuals responsible for history’s greatest architectural works.

In November 1958, local politicians and angry mothers gathered in New York City’s Washington Square Park for a ribbon-tying ceremony. The activists arranged the photo-op—a sly inversion of a ribbon-cutting —as a cheeky victory lap.

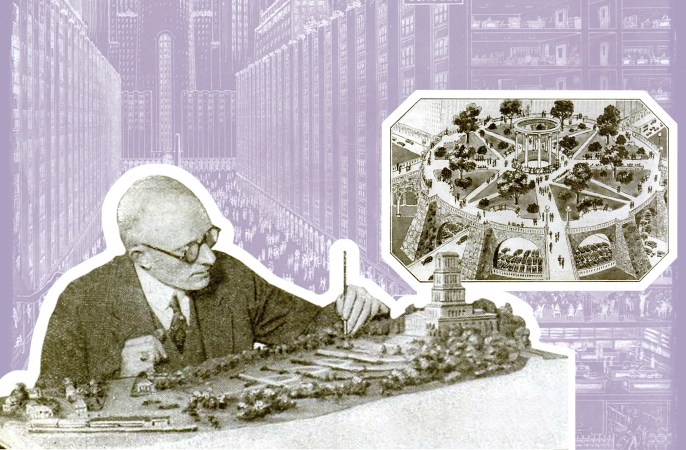

The crew had spent the better part of three years in a bureaucratic street fight with the city’s master builder, Robert Moses, who, in 1955, renewed his longstanding call to extend the four lanes of Fifth Avenue through the park’s iconic arch. The women of Greenwich Village refused to stand by as urban planners ripped their greenspace in half. The activism of the “militant dames,” as one male architect labeled them, ensured that the downtown landmark would remain forever closed to automobiles.

Many figures played a role in the victory. Shirley Hayes, a mother of four, created a committee to save the park. Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, once a resident of Manhattan’s Upper East Side, joined the masses at City Hall to support the cause. But preeminent among them was Jane Jacobs, a writer and city planning activist raising a family on nearby Hudson Street.

A tall woman with a wispy white bob, Jacobs wrote fiercely for publications like Architectural Forum about what defines a good cityscape. She favored a hodge-podge of old and new structures, an engaged community of people who watched out for each other, and buildings that combined commercial and residential space. Her forward-thinking books, particularly the 1961 classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities, challenged conventional practice on urban planning, which favored centralized design and control. Her writings made Jacobs a controversial figure, but also one who established new rules that municipalities follow today. Where Moses and other “master builders” preferred razing old homes and paving new streets, she called for preserving the “weird wisdom” of communities. She was the unbuilder.

Jacobs’s work built on a long tradition of architectural activism. “The impulse to save things and preserve them is actually quite old,” says Tom Mayes, vice president and senior counsel for the National Trust for Historic Preservation; such endeavors date at least to the effort by imperial Romans to safeguard a hut believed to be the birthplace of Romulus, the city-state’s first king. In the U.S., the movement started in the 1850s when the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association raised $200,000 (almost $6 million today) to buy and restore George Washington’s plantation home.

Still, the efforts did not coalesce into a national movement until the middle of the 20th century, when municipal governments began replacing communities with city-run housing developments. In New York City, officials pushed more than 250,000 residents from their homes in a process they called “slum clearance.” Such projects disproportionately affected people of color, leading novelist and playwright James Baldwin-whose work often explored racism-to say that “urban renewal is negro removal.”

It wasn’t just homes and corner shops: Developers mowed down historic structures in cities nationwide during the 1960s and ’70s. Detroit’s City Hall in 1961. New York City’s Penn Station in 1964. The Chicago Federal Building in 1965, followed by Louis Sullivan‘s Chicago Stock Exchange in 1972.

Preservationists learned from such losses. In Charleston, South Carolina, local activist Frances Edmunds directed the Historic Charleston Foundation to create a fund buy old homes to save them from destruction in 1957. In Denver, an effort by architecture conservationist Dana Hudkins Crawford to save Larimer Square, the city’s founding neighborhood, culminated in it being named the burg’s first historic district in 1971. In New York, former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis lent the Municipal Arts Society her celebrity and political contacts to help save Grand Central Terminal from demolition in 1978.

Jacobs also continued to take her beliefs to the streets-literally. In the late 1960s, she once again squared off against Moses to stop construction of the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have sacrificed the Lower East Side and SoHo neighborhoods to connect Brooklyn to New Jersey. Again, she won.

Jacobs was a staunch advocate of such efforts, but held bigger ambitions. She wanted to protect the integrity of blocks, neighborhoods, districts, and even whole cities.

Born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1916, Jacobs moved to New York City with her sister in 1935. She left Columbia University’s School of General Studies after two years to pursue journalism. Jacobs was an intrepid—and opinionated—reporter with a knack for complex topics, including women’s right to equal pay and the importance of union organizing. In 1952, she joined Architectural Forum, and focused on city planning. She lectured at Harvard on the devastating effects of urban renewal on Harlem. She joined the committee to save Washington Square Park. And she launched the project, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, that would become her most significant work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

Urban planning students have read the 1961 monograph for almost 60 years. Jacobs spent three years visiting Philadelphia, Boston, New York, and other cities to observe how people used their streets and neighborhoods. She distilled her findings into several core requirements of good planning. Streets must be lively, with people coming and going at all hours. Roadways must also serve as a continuous connection between residents. Where there was an obstruction, such as highways without pedestrian crossings, there should be a developer ready to remove it. And instead of designing a centralized, modernist city like the Brazilian capital of Brasilia—which divided work, living, and recreation into discrete zones—Jacobs argued for mixed-use communities, where parks, public buildings, homes, and offices mingled.

Jacobs also believed each community should possess its own identity. Emily Talen, in her book Neighborhood, which frequently cites Jacobs, says this shared sensibility can be the product of exclusion, typically around ethnic, racial, or class distinctions. These days, though, developers tend to use branding to encourage social cohesion: They name an area (Wicker Park in Chicago, for example, or Capitol Hill in Seattle), establish clear boundaries, and erect corresponding signage. But as Jacobs warned, what worked in one place wouldn’t necessarily work in another. To successfully forge a shared identity—as the hip nightlife area, say, or the art district—each neighborhood must start doing so from its beginning.

This was how cities historically grew: spontaneous development, orchestrated—and occasionally improvised—by residents. You see this in eclectic neighborhoods like Greenwich Village, which emerged centuries before the rest of Manhattan and doesn’t follow the city’s grid layout, or in industrial zones rehabilitated by artists. This contrasted with the approach of master builders like Moses, who considered the city from a bird’s-eye view. Modernists like him looked to maps, aerial surveys, and abstract theory instead of the natural ebb and flow of activities on the street. That placed the fate of a community in the hands of people who systematically minimized, if not ignored, the experiences of those who lived there.

Jacobs sought to better articulate and amplify the knowledge of neighborhood residents. She found abundant evidence of the average person’s ability to shape a community: In one chapter of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs famously concluded that safety was the result of “eyes on the street,” a term she coined for citizens watching over things from stoops or windows and intervening when they saw something amiss.

This cooperative approach contrasted with the planning theory of the day, which considered safety a function of design. Many low-income residents saw their homes levelled and replaced by city-run housing. The buildings were orderly, clean, and arranged in large complexes drawn back from the street—all attempts to foster community and security. But people who once knew and cared for their neighbors found themselves adrift among strangers. The enormous structures featured concealed stairways and long corridors that prevented residents from interacting with each other. People’s sense of involvement in, and responsibility over, their spaces eroded. Without eyes on the street, crime increased.

Jacobs wasn’t anti-development, but she favored mixed-use projects—typically buildings with businesses on the first floor and apartments above. In every city she visited, she found that thriving neighborhoods saw round-the-clock use. In the morning and evening, residents made their way to and from work. At night, they gathered at bars and restaurants. There were always people on the streets, ensuring not just safety, but also interpersonal connection and a healthy local economy.

Prominent figures in architecture lambasted Jacobs’ book. For many, the criticism was almost as bad as the fact that it came from a woman. In his New Yorker essay “Mother Jacobs’ Home Remedies,” literary critic Lewis Mumford said the book had “a mingling of sense and sentimentality, of mature judgments and schoolgirl howlers.” But over time, Jacobs’ ideas seeped into school curricula, and eventually into cities themselves.

In 1986, Toronto—where Jacobs and her family moved during the Vietnam War—became one of the earliest cities in North America to adopt mixed-use zoning. By the early 1990s, developers were experimenting with the approach in cities like Portland, Oregon, and Berkeley, California. Municipal governments across the nation have since revised zoning laws to embrace such multipurpose design.

Nowadays, you’d be hard-pressed to find a redevelopment project that doesn’t feature restaurants, tap rooms, bookstores and other retail establishments at street level, and homes up top. This maximizes space and makes the neighborhood more “walkable,” meaning residents can find many points of interest in a small area—and access them via safe, well-maintained sidewalks and paths. Advocates of this layer-cake strategy say it reduces noise and air pollution, creates more affordable housing, and helps each community forge a unique identity.

Critics often note that Jacobs’ ideals frequently lead to gentrification. She loved old buildings because they were cheap to rent at the time. These days, they’re typically the most coveted, and therefore priciest, homes on the block. Jacobs’s naysayers also say she failed to anticipate the resurgence of the American city. She wrote in a time of “white flight,” when wealthy white residents left for the suburbs, decimating tax bases. When those residents returned, they put pressure on the existing building stock she so prized, making large-scale development inevitable.

Today, Washington Square Park looks much like it did in the 1989 film When Harry Met Sally or the 1967 movie adaptation of Barefoot in the Park— timeless. The marble triumphal arch frames the glassy One World Trade Center skyscraper, but remains unchanged since 1892. American elms, driven to extinction in most of the country by a voracious beetle, stand tall. Students, tourists, and parents with stroller-bound children mosey around the central fountain, unharried by cars.

It’s a classic New York City scene, but you’ll find Jacobs’ most lasting legacy in every neighborhood that retains its unique flavor. Where new buildings co-exist with, rather than replace, old ones. And, most important, where people have a say in how their community grows and changes. “Mother Jacobs” stood up to the giants of urban planning and pointed the way toward a more collaborative vision of the future city.