Ernest Hemingway’s Florida home is ready to withstand its 168th hurricane season

Since its construction in 1851, the limestone structure has stayed remarkably "high and dry."

With Hurricane Irma bearing down on Florida, the team at the Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum in Key West had an important decision to make: What should be done to protect the 54 historic cats that live on the property, many of which are descended from the author’s very own felines? One option was to launch an evacuation, packing the cats in crates, and driving their way to the mainland. The other was to shelter in place, trusting the 167-year-old house to keep the staff and their prized 6-toed pets safe, even as a category 4 storm raged nearby.

To the surprise of many media outlets, Dave Gonzales, the museum’s executive director, chose the latter option. Several staff members decided to remain in the historic home with the cats—and a bevy of emergency supplies, from veterinary medicine to bulk Gatorade. While Gonzales stresses that his decision should not be a model for others (no one should follow the Hemingway House’s lead and shelter in place if evacuating is a safer choice for them), the staff seems to have had a nice time, all things considering. “Besides the downed trees we were having to carve around us, and picking up the debris around us, we were living and eating normally,” he says.

The reasons for this normalcy are up for debate. Some attributed it to Hurricane Irma’s last minute deviation from its projected course, which ravaged the middle Keys, but left Key West and many of its historic homes relatively unscathed. Others, more critical of the decision to shelter in place and ignore the government-mandated evacuation, called it sheer dumb luck. But Gonzales says it was the Hemingway Home’s unique architectural qualities that kept his crew safe. (Well, that and a priest’s blessing, bestowed on the iconic cats and their human keepers shortly before the storm hit.)

“We have probably the strongest fortress on the island that is not only a safe structure, but has been there since 1851 with zero structural damage,” Gonzales says. While climatological records remained spotty until the late 19th century, this means the house has successfully weathered approximately 20 hurricanes and tropical storms that have historically pummeled Key West—and the corresponding onslaught of wind and water. In a climate changed era, where once-rare storms seem increasingly common and resilient engineering is on the mind of many architects and city officials, one has to wonder, what is this house doing right?

Southern Florida was originally inhabited by Native Americans. But the recorded history of the region string of islands today known as the Florida Keys begins with the Spanish, who colonized the area in the 16th century. The conquistador Juan Ponce de León initially named the archipelago the “Los Martires” islands, which is Spanish for “the martyrs.” Five hundred years later, his reasoning remains unclear, but the name is fittingly foreboding.

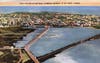

Like a broken necklace, the Key’s countless specks of limestone and coral curve west around the tip of Florida. Until 1912, when a railroad was erected, one could only reach Key West, the farthest island in the chain and the location of the Hemingway Home, by boat. Today, the Overseas Highway and its 42 bridges do the job, but only if one deems Margaritaville worth the 113-mile-long drive. Naturally, the narrow passageway generates gridlock even on the laziest afternoons. In the midst of an evacuation, which are called every few summers as mighty Atlantic hurricanes swirl around the exposed islands, traffic grinds to a complete halt.

Despite de León’s early warning, sun-seekers and shipwreck salvagers eventually populated the Keys. In 1850, when construction on Asa Tift’s mansion at 907 Whitehead Street was nearing completion, the census tallied 2,367 residents living on Key West alone. Among them was Tift, who’d made a small fortune recovering the many marine vessels—and their corresponding cargo—shipwrecked off the coast. He decided to use that money to build a tropical palace, across the street from the soaring Key West lighthouse.

Today, Tift’s stately home still has pride of place on the island. It’s painted avocado and key lime, draped in palms, and boasts a lush green lawn. Each year, it’s visited by thousands of tourists and is a destination for dozens of weddings and other events. But the visitors aren’t there to learn more about Tift (though the avowed Confederate is immortalized in the Key West Shipwreck Museum at the end of Whitehead Street). Rather, the masses assemble for Nobel Prize-winning novelist Ernest Hemingway, who lived in the house from 1931 to 1939. In his backyard studio, Hemingway wrote such acclaimed short stories as “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” and tended to his cat, Snow White, whose world-famous polydactyl descendants live on the property to this day.

But it was Tift who built the house. And, Gonzales says, it was Tift who built it right.

From President Harry S. Truman’s “Little White House” on Front Street to Shel Silverstein’s house on William Street, which was completely crushed by a felled ficus Irma uprooted, the architecture of Key West is wood, through and through. That’s how Old Town, the historic heart of the island, earned the distinction of having the highest concentration of wooden structures of any district listed on the federal government’s National Register of Historic Places. But Tift took another route, building his home from 18-inch thick limestone blocks, dug up from the bedrock beneath the construction site. In doing so, Gonzales says Tift created something akin to “a vault or Fort Knox”—not a bad idea when you’re smack in the middle of hurricane alley.

Tift had another storm-proofing trick up his sleeve: His breezy abode is built on the second-highest point in Key West, some 16 feet above sea level. Only the Key West Cemetery is on higher ground, which sits 18 feet above sea level. When Hurricane Wilma hit the island in what the National Weather Service deemed the “hyperactive 2005 season”, it brought with it one of the highest storm surges ever seen in the Keys. But even then, Gonzales reports, “We were high and dry. No water accumulation whatsoever.”

Careful preparation, such as stockpiling necessities, securing the storm shutters, and covering windows with plywood, is imperative. But Gonzales says it’s these two structural features—what the Huffington Post termed a “limestone fortress,” and some serious elevation—that have kept the structure standing even as neighboring homes faltered.

Craig Fugate knows a thing or two about natural disasters—especially those that regularly threaten his home state. Before he served as the administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, from 2009 to 2017, he was the director for emergency management for the state of Florida. In that role, Fugate oversaw the response to the “Big 4 of ‘04,” when Hurricanes Charley, Frances, Ivan, and Jeanne pummeled the panhandle state in short order. In the process, he witnessed firsthand how evidence-based construction and rigorous enforcement of building standards could minimize the misfortune wrought by a storm.

Retired from FEMA and back in Florida, Fugate described a street walk he did with then-President George W. Bush and his brother, then-Florida Governor Jeb Bush shortly after a serious storm had subsided. As the politicians and press ambled through the disaster area, talking with homeowners and surveying the damage, people began to remark on the difference in how local homes were affected. On the same block, ranch homes from the 1960s and 70s were blown to smithereens, while more recent construction, built after Florida began to enforce the nation’s most stringent structural safety rules, looked good as new. “Bush turned to his brother and basically said, ‘What gives?'” Fugate recalls. “And Jeb just said, ‘Building codes.'”

New construction in Florida must now meet a few key requirements. For one, exterior glass surfaces like windows and sliding doors need to be reinforced with storm shutters or reinforced glass, lest they shatter in the face of flying debris or fearsome winds. Roofs must also be fortified; fortunately, a relatively inexpensive shift from smooth standard nails to the toothy ring shank nails increases durability dramatically. Most importantly, homes in the path of potential destruction need hurricane clips, also called hurricane ties. The small steel devices, each of which costs under a dollar, firmly connects a building’s rafters with its walls, dramatically increasing the amount of uplift (that is, wind pressure) a structure can cope with before lifting off.

Together these wind-proofing methods can help to preserve the outer shell of a structure and, in the process, keep a storm’s other worst side effect—water damage—at bay. After a roof is torn off or windows are busted open, Fugate says it’s easy for rain and storm surges to fill the house, causing walls to degrade and allowing mold spores to thrive, among other problems. “If you started seeing the roof fail, it was likely the rest of the house would follow,” he says. “Protecting the envelope of the home was protecting the rest of the house.”

In our wide-ranging phone conversation, Fugate provided anecdote after anecdote of his disaster relief work around the state of Florida, all illustrating that the date of construction was the biggest predictor of a house’s performance in a given storm. (“It was almost Goldilocks and the Three Bears,” he said of another streetwalk in the middle Keys. “The three houses: One destroyed, one beat up, one salvaged.”) So what to make of that 157-year-old structure, down in Key West?

Fugate says many of the Hemingway Home and Museum’s key features are surprisingly strategic, especially considering its age. “That kind of construction, the heavy masonry construction, is great to brace against wind,” he says of the limestone. And elevation, which the Key West facility has in spades, is an even bigger boon, according to Fugate. What the house has naturally—16 feet between its hardwood floors and sea level—is something people up and down the east coast are paying tens of thousands of dollars to get artificially, in the form of homes raised up on stilts, away from the hungry ocean and its rising tide.

Not everyone is so convinced. Illya Azaroff is the founder of the American Institute of Architects’ Design for Risk and Reconstruction Committee and an expert in resilient buildings. He says that the benefits of limestone construction aren’t so clear cut. “I would question if it’s better than any other material,” he says. Still, Azaroff acknowledges the naturally high elevation of the site is undeniably advantageous, as are many of the smaller livability features. “There’s a natural alignment to the vernacular of the environment,” he says of the house. In architecture, vernacular is a shorthand for buildings, typically constructed in a hyperlocal style, that prioritize function over everything else. “It’s orientation to the sun, it’s orientation to the wind, cross-breezes through the house—that’s [also] about resilience,” he says.

For all the time and money being poured into resilient design, Fugate, Azaroff, and many of their colleagues agree there will never be a totally disaster-proof home. The Hemingway House has made it this far, but there’s nothing to say the next storm won’t strike the museum a major blow. The same is true even for houses built with tougher nails and lifted on stilts. These features keep the wind and water out of many Floridian homes right now, but a time may come when it just doesn’t make sense to live in the Keys—or any number of other vulnerable places—anymore.

We can and should work to design hardier structures, but hurricanes will always be stronger than humans, according to Azaroff. And, he notes, even if there was a perfectly weatherproof home, it wouldn’t really matter if you were completely disconnected from the outside world. No matter how big your stockpile is, you’d eventually require more food, gas, or emergency services like an ambulance or firetruck, only to find those services have been suspended. “I have to consider that infrastructure I use to support my community and my house,” he says. Otherwise, “I’m putting others at risk.” That’s why, even if your home meets all the latest codes, evacuation orders should be heeded. It’s also why the places humans choose to settle could soon look a little different. “The traditional patterns of living in the United States… may not work in the future,” Azaroff says.

Walking the grounds of Hemingway’s house, visitors can stop and photograph any number of eccentric features. There’s the cat’s elaborate outdoor water bowl, which legend has it was fashioned from a urinal Hemingway stole from his favorite local bar, Sloppy Joe’s. There are typewriters, movie posters, and books. Animals are mounted on the walls and elaborate gardens bloom outside. There’s even a cat cemetery, where Bubba, Tigger, and their kin have been laid to rest. But for those in the know, the most compelling feature of the Hemingway Home and Museum may just be what you don’t see: damage from more than a century’s worth of storms.