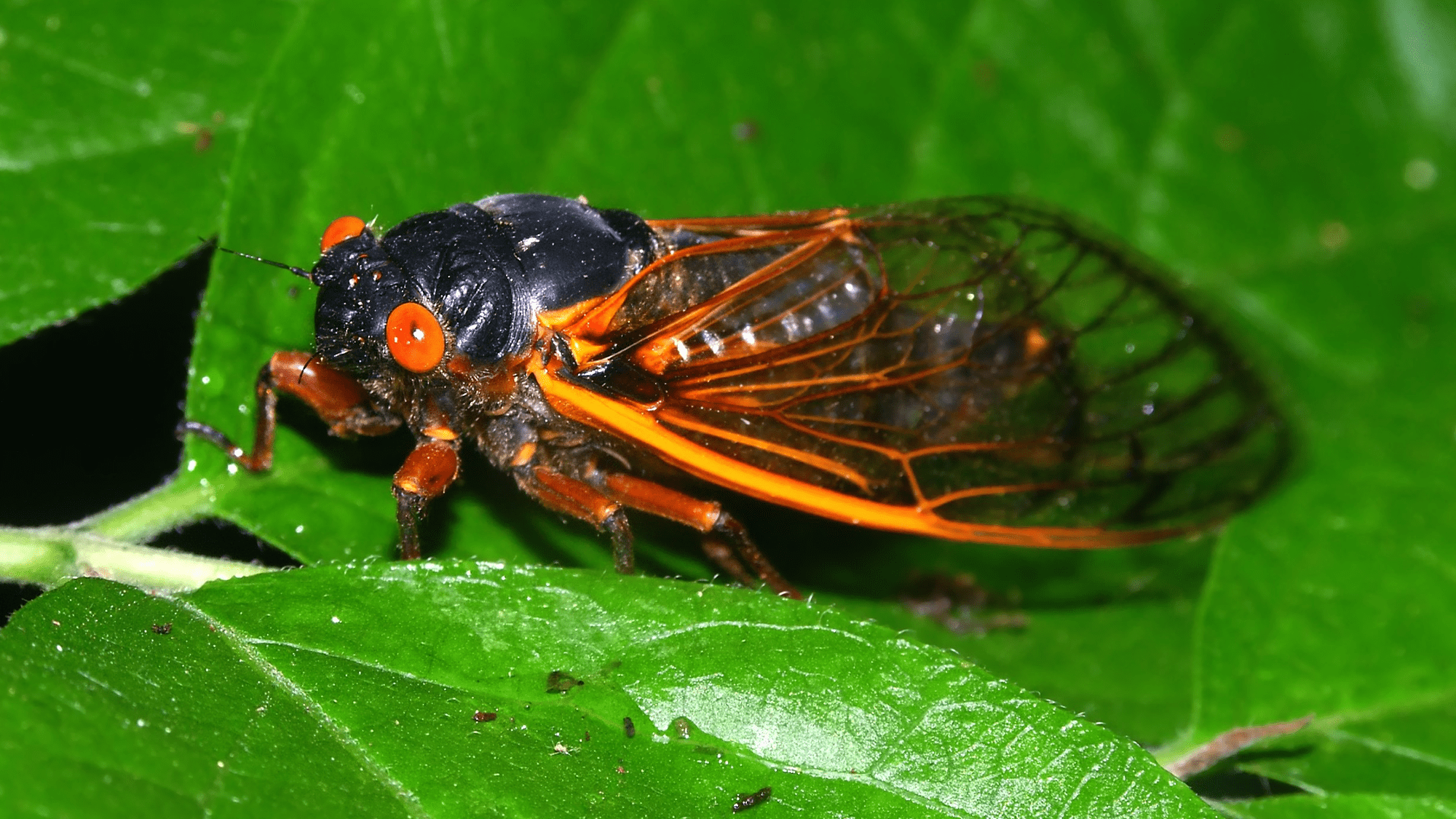

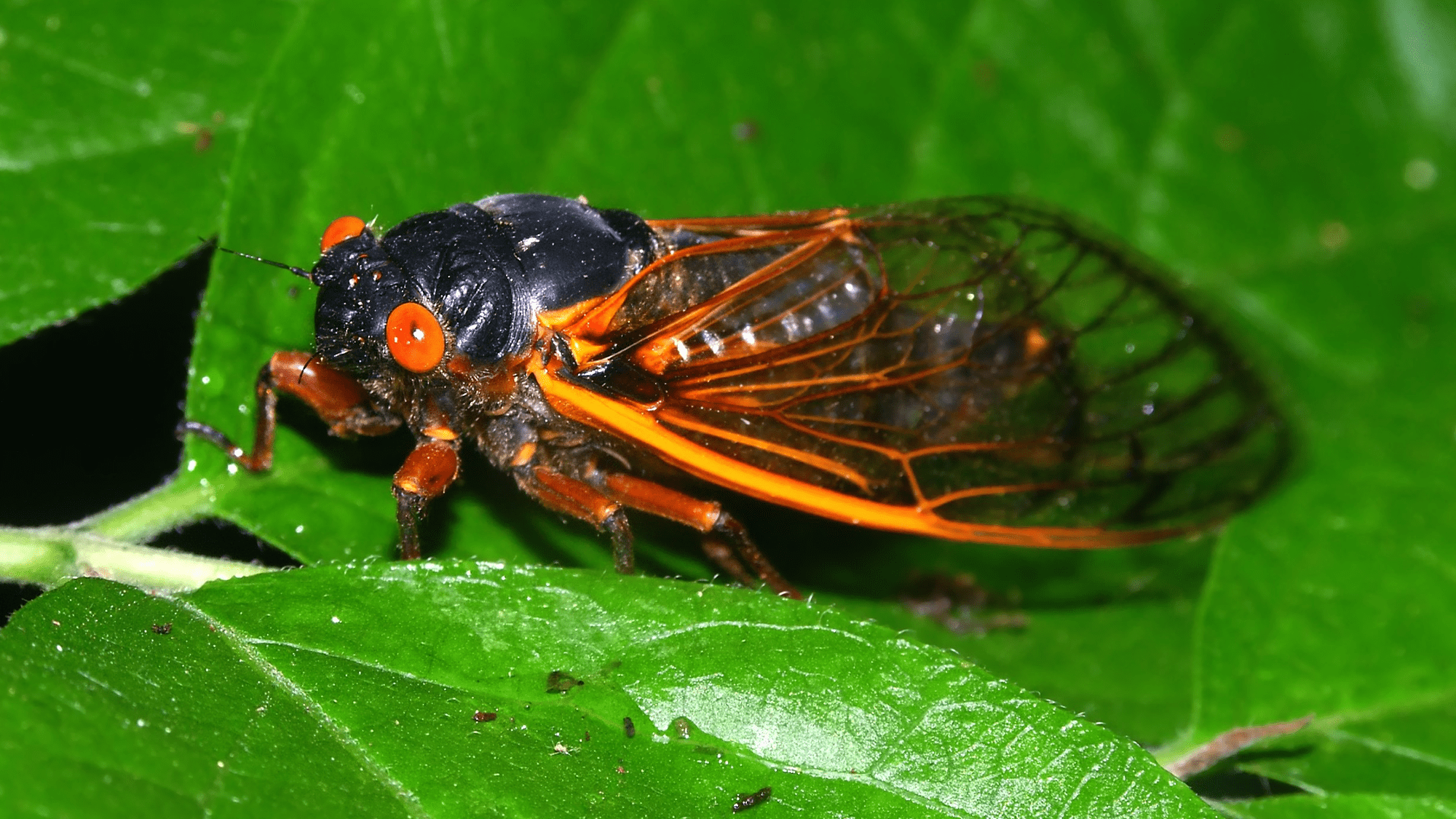

Every 13 or 17 years, the buzzy mating call of billions of cicadas is the soundtrack of the summer in some parts of the United States. Their clicky noises are so loud that they could potentially be detected by the same fiber optic cables that help deliver high-speed internet. A proof-of-concept study published November 30 in the Entomological Society of America’s Journal of Insect Science describes how this technology could help track the these loud and fleeting insects

[Related: The Brood X cicadas are coming, and you should eat them. Here’s how.]

When hung on a utility pole, fiber optic cables can be used as a sensor to detect changes in temperature, vibrations, and very loud noises. This emerging technology is called distributed fiber optic sensing and it was tested in the study.

“I was surprised and excited to learn how much information about the calls was gathered, despite it being located near a busy section of Middlesex County in New Jersey,” study co-author and entomologist Jessica Ware said in a statement. Ware is the associate curator and chair of the Division of Invertebrate Zoology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Measuring ‘backscatter’

According to the team, distributed fiber optic sensing is based on finding and analyzing the backscatter when an optical pulse is sent through a fiber cable. Backscatter occurs when small imperfections or disturbances in the cable cause a tiny amount of the signal to bounce back to the source. Technicians can time the arrival of the backscattered light to calculate exactly where along the cable the light bounced back. Monitoring how backscatter varies over time creates a signature of the disturbance. In acoustic sensing, this signature can indicate the frequency of the sound and volume in the cable.

One sensor can also be deployed on a large segment of cable. According to the study, a 31-mile-long cable with a sensor can detect the location of disturbances at a scale as precise as 3.2 feet. The authors report that this is identical to installing 50,000 acoustic sensors in a tested region that not only synchronized, but don’t require an onsite power supply.

However, according to co-author and NEC Labs America photonics researcher Sarper Ozharar, acoustic sensing in fiber optic cables “is limited to only nearby sound sources or very loud events, such as emergency vehicles, car alarms, or cicada emergences.”

Return of Brood X

In 2021, the Brood X population of cicadas emerged from the ground in at least 15 states. Brood X is the largest of several populations of cicadas that emerge on 17-year cycles. Ozharar, Ware, and colleagues from NEC Laboratories America, Inc. took this opportunity to use the lab’s fiber-sensing test apparatus to see if they could pick up the Brood X cicadas buzzing in trees. The cable was cable strung on three 35-foot utility poles in Princeton, New Jersey between June 9 and June 24, 2021.

[Related: The world’s internet traffic flows beneath the oceans—here’s how.]

The cable picked up the insects’ sounds. The buzzing appeared as a strong signal at 1.33 kilohertz (kHz) via the fiber optic sensing. This matched the frequency of the cicadas’ call when it was measured with a traditional audio sensor in the same location.

The team also saw the cicadas’ peak frequency varying between 1.2 kHz and 1.5 kHz. This pattern appeared to follow changes in air temperature. The fiber optic sensing also showed the overall intensity of the bugs’ noise over the course of the testing period. The signal decreased over time, as the cicadas’ sounds peaked and then faded as they approached the conclusion of their reproductive period.

“We think it is really exciting and interesting that this new technology, designed and optimized for other applications and seemingly unrelated to entomology, can support entomological studies,” said Ozharar.

Fiber optic sensors are multifunctional, so they can be installed and used for any number of purposes, detecting cicadas one day and some other disturbance the next. They could also be used to detect a variety of different insects, according to Ware.

“Periodical cicadas were a noisy cohort that was picked up by these systems, but it will be interesting to see if annual measurements of insect soundscapes and vibrations could be useful in monitoring insect abundance in an area across seasons and years,” said Ware.

Brood X cicadas are back underground and will not emerge until 2038. The long gap between their appearances does allow entomologists to make technological leaps in the interim. Using a mobile smartphone or an app was not feasible when Brood X last emerged in 2004, but both technologies heavily documented the 2021 emergence. Fiber optic cables could lead to a similar technological leap in cicada chorus study.