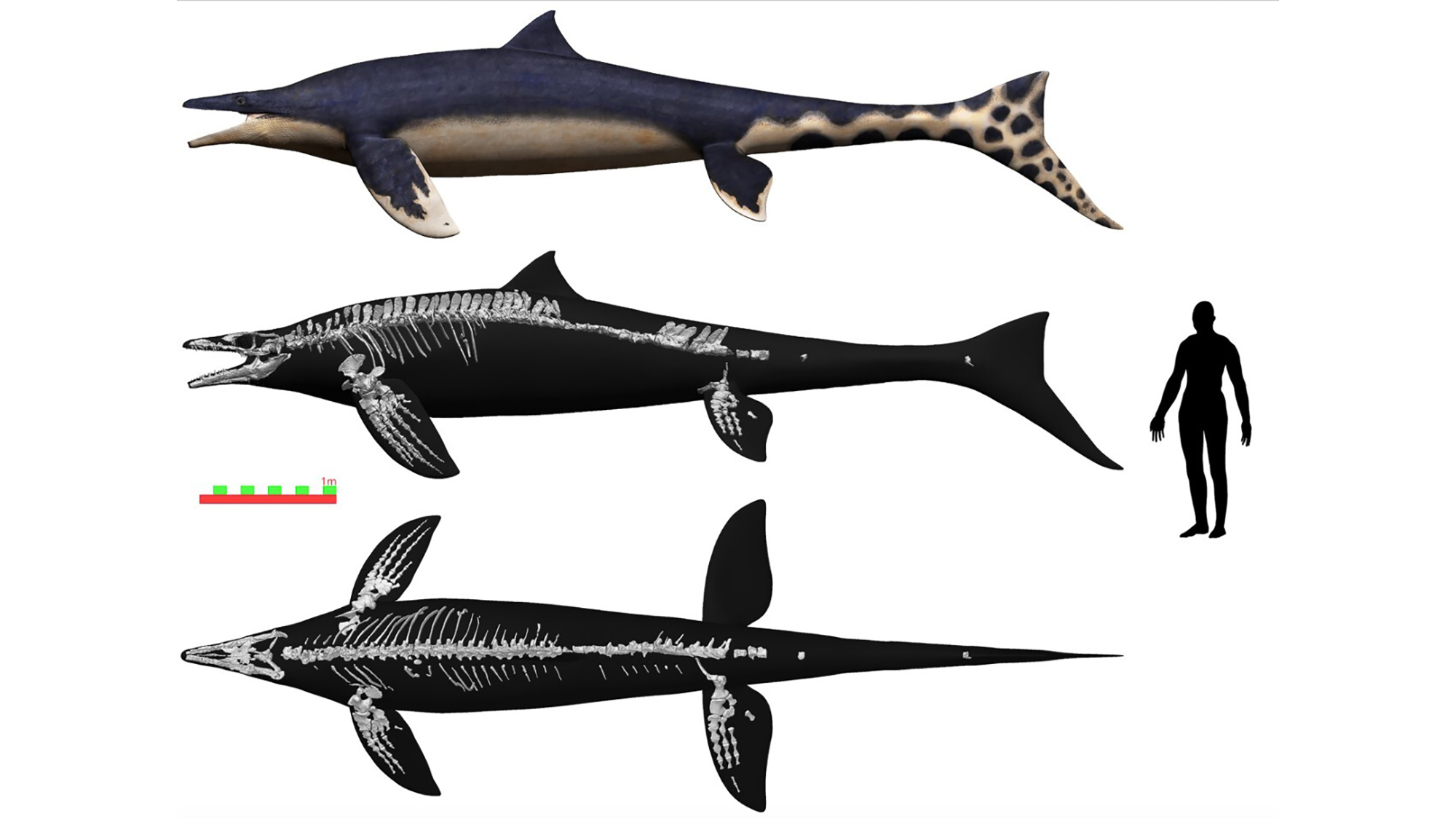

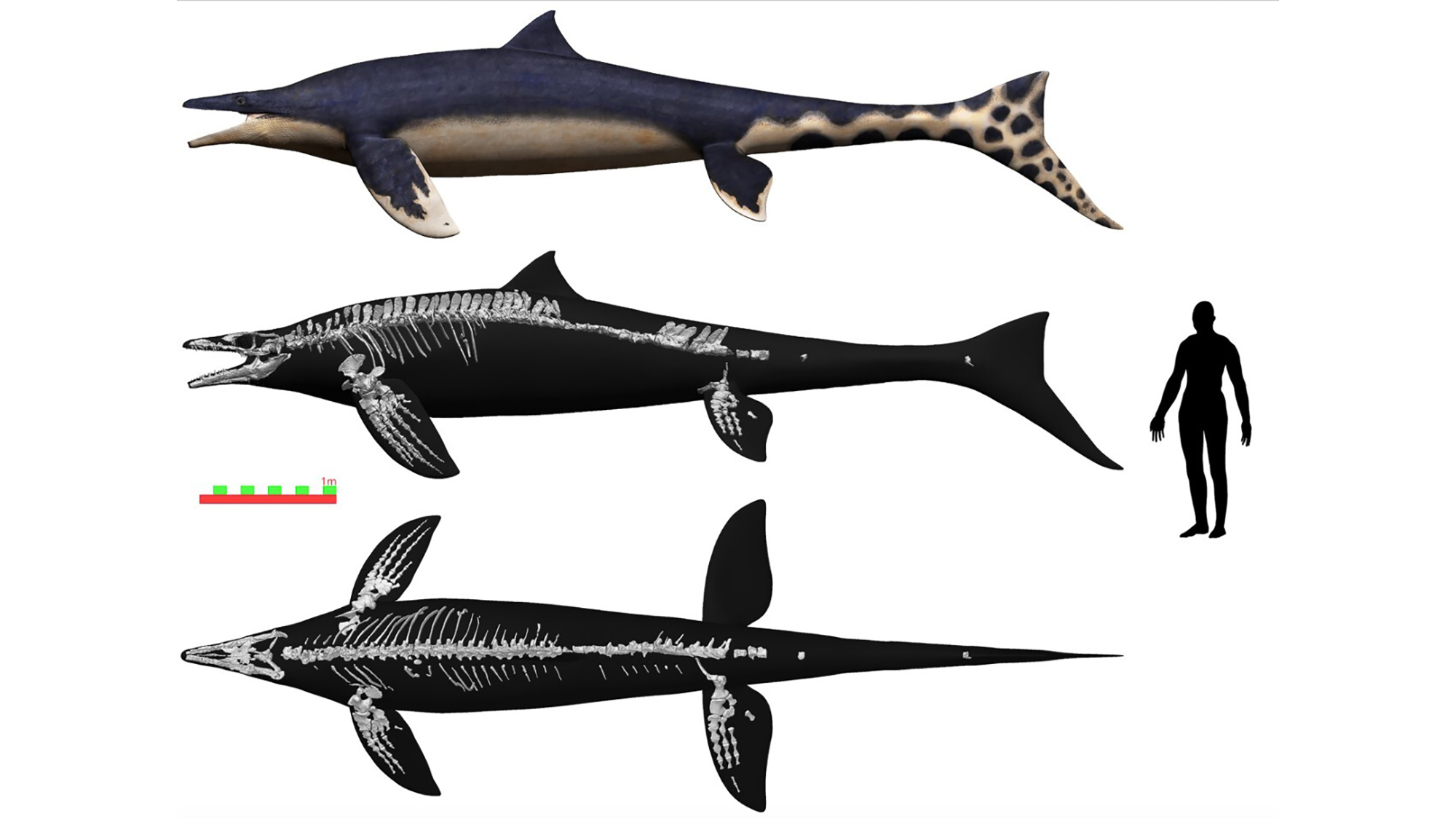

About 72 million years ago, a mosasaur the size of a modern great white shark terrorized the Pacific Ocean. Nicknamed Wakayama Soryu or “blue dragon,” the large extinct marine reptile was propelled by extra-long rear flippers and a long finned tail. Wakayama Soryu also had a unique dorsal fin like a shark or dolphin. This back fin would have helped it turn very quickly and precisely in the water, making Wakayama Soryu a formidable foe. This newly described reptile is detailed in a study published on December 11 in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

[Related: Newfound mosasaur was like a giant Komodo dragon with flippers.]

Mosasaurs were marine apex predators that lived when Tyrannosaurus rex and other late Cretaceous dinosaurs dominated life on land. They ate cephalopods, fish, sharks, birds, and were even known to munch on other mosasaurs. Mosasaurs died off during the same mass extinction event that killed almost all of the dinosaurs about 66 million years ago. Mosasaur specimens have been uncovered all over the world, including in North Dakota, The Netherlands, and Morocco.

Wakayama Soryu was found along the Aridagawa River in Wakayama Prefecture along the central coast of Japan. Its dragon nickname is a reference to Japanese folklore.

“In China, dragons make thunder and live in the sky. They became aquatic in Japanese mythology,” study co-author and University of Cincinnati vertebrate paleontologist Takuya Konishi said in a statement.

The specimen was first discovered in 2006 along by study co-author Akihiro Misaki from the Kitakyushu Museum of Natural History & Human History. Misaki was searching for ammonite fossils when he spotted an interesting dark fossil in the sandstone. A closer look at the dark stone revealed that it was a back bone and part of the most mosasaur skeleton ever found in Japan of the northwestern Pacific.

“In this case, it was nearly the entire specimen, which was astounding,” Konishi said.

Konishi has spent decades studying ancient marine reptiles, but this new specimen had some features that defied simple classification. The rear flippers are longer than the front flippers and are even longer than its head.

“I thought I knew them quite well by now,” Konishi said. “Immediately it was something I had never seen before.”

The Wakayama Soryu has some features that are similar to mosasaurs found in New Zealand and is fairly comparable to a mosasaur specimen found in California. Konishi said it also had nearly binocular vision that would have made it a deadly hunter.

The team categorized the new specimen in the subfamily Mosasaurinae and gave it the scientific name Megapterygius wakayamaensis, to recognize where it was discovered. Megapterygius means “large winged” in keeping with the mosasaur’s enormous flippers. The paddle-shaped flippers were potentially used for locomotion. Another prehistoric marine reptile called the plesiosaur used paddle fins for propulsion, but it was not equipped with a rudder-like tail the way Wakayama Soryu does.

[Related: Megalodon’s warm-blooded relatives are still circling the oceans today.]

“We lack any modern analog that has this kind of body morphology—from fish to penguins to sea turtles,” Konishi said. “None has four large flippers they use in conjunction with a tail fin.”

The team believes that these large front fins might have helped with rapid moving, while the rear fins would have given pitch to dive down or surface. Like other mosasaurus, the tail would have generated powerful and fast acceleration during hunting.

“It’s a question just how all five of these hydrodynamic surfaces were used. Which were for steering? Which for propulsion?” said Konishi. “It opens a whole can of worms that challenges our understanding of how mosasaurs swim.”

The orientation of the neural spines along the Wakayama Soryu’s vertebrae indicate that it had a dorsal fin, unlike other mosasaurs. The neural spines are arranged in a way that is similar to present-day harbor porpoises, which also have a prominent dorsal fin.

“It’s still hypothetical and speculative to some extent, but that distinct change in neural spine orientation behind a presumed center of gravity is consistent with today’s toothed whales that have dorsal fins, like dolphins and porpoises,” Konishi said.