If you give a lab mouse the mouse version of Ebola, it will die. But not in the same way humans with Ebola do. Lab mice infected with Ebola don’t get hemorrhagic fever. They don’t form tiny clots in their blood, like human Ebola sufferers do, even though the genetic sequence of the mouse Ebolavirus differs from human Ebolavirus in only 13 out of its nearly 19,000 genetic letters.

Now, however, a team of U.S. biologists has bred mice that–unlike most lab mice–can get Ebola. Like people, the newly minted mice don’t all react the same to an Ebola infection. Some die with internal bleeding, swollen spleens, and damaged livers. Some lose weight after getting infected, but eventually recover with no lasting damage. Others suffer symptoms somewhere between those two extremes.

The situation is analogous to what happens in humans. Some proportion of people who get Ebola infections die, while others recover. Even those proportions are roughly the same in people and in the new mice, says Angela Rasmussen, a biologist at the University of Washington who worked on breeding the mice. Depending on the outbreak, about half of people who contract Ebola die. Eighty percent of Rasmussen’s mice are susceptible to severe Ebola symptoms, and a little more than half of those mice die from their infections.

Outside of the quality of medical care they get, it’s unclear why some folks are spared. The mice point to one possible reason. They are genetically diverse, but those with more similar genetics seemed to react similarly to Ebola infections. That suggests victims’ DNA play a role in how their bodies react to Ebola.

“They do represent a genetically diverse population that’s analogous to humans.”

In fact, Rasmussen thinks the varying genes within the population of mice she made is the reason they get human-like Ebola symptoms, whereas previous generations of lab mice didn’t. “Most classical laboratory strains are really only representing 10 percent of the potential genetic diversity over the entire mouse species,” she tells Popular Science. Those mostly uniform lab mice just happened not to be vulnerable to getting Ebola symptoms. The new lab mouse population, on the other hand, “covers about 90 percent of the genetic diversity across the entire mouse species,” she says.

Their genetic differences makes them a better reflection of people, too, Rasmussen thinks. “They do represent a genetically diverse population that’s analogous to humans.”

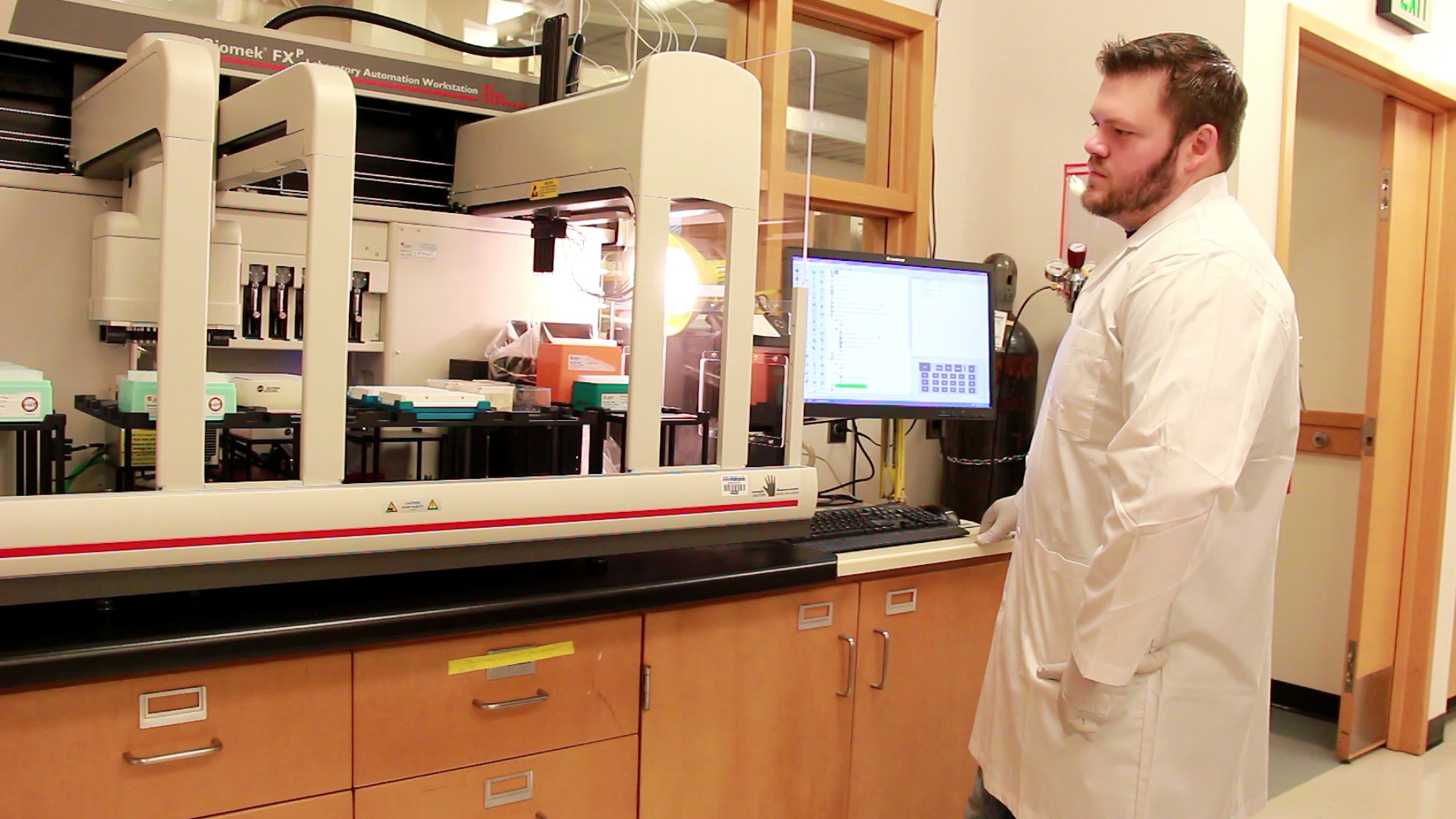

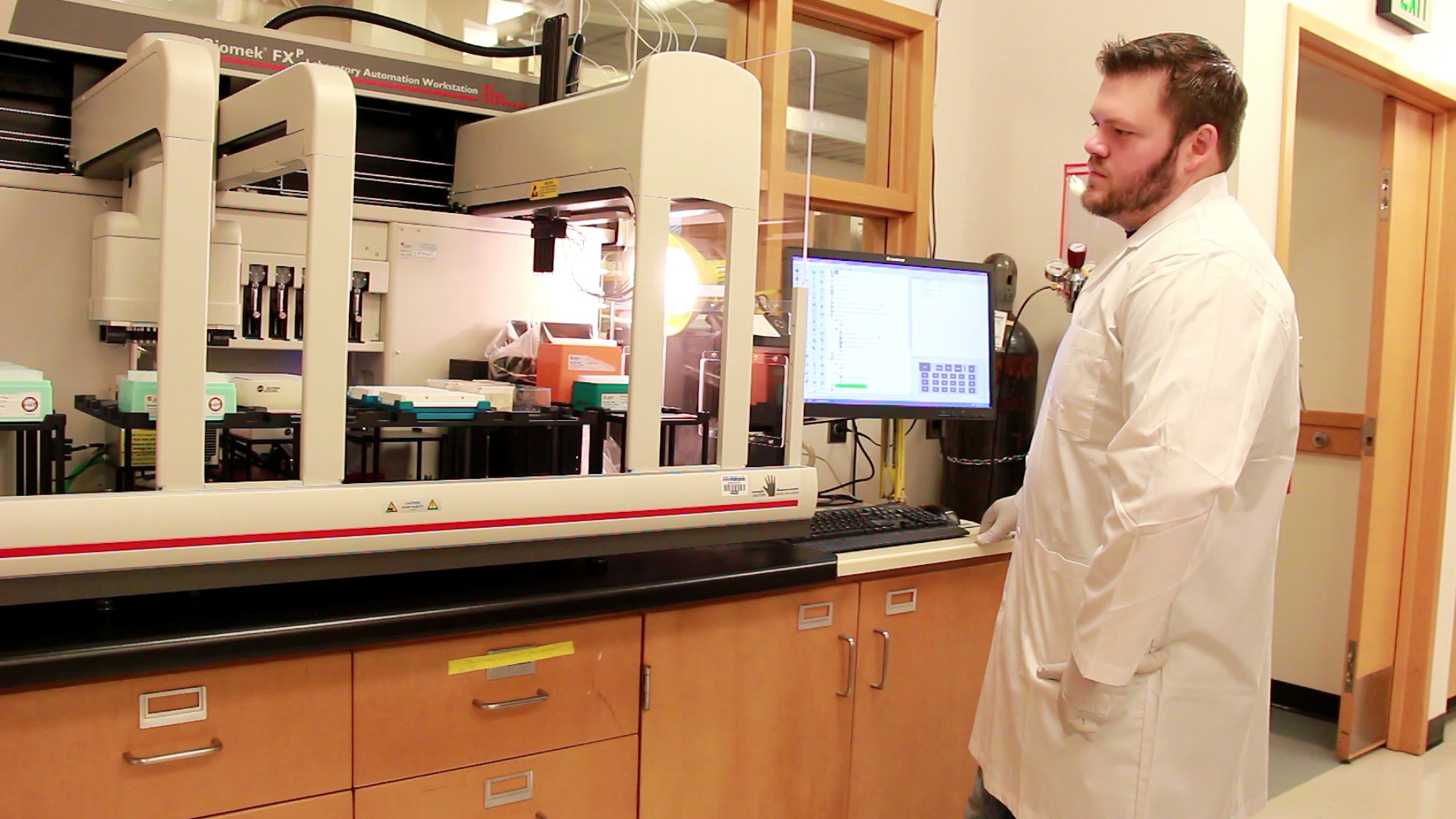

Rasmussen and her colleagues—a team including biologists from various university and government labs in the U.S.—are now examining their mice to see which genes are associated with recovering from Ebola, and which are associated with dying from it. At the same time, the researchers are making the Ebola-infectable mice available for other researchers to order and use in their own experiments on Ebola. They’re hoping the diverse mice will make Ebola research a bit easier on their peers.

Not being able to do studies in mice is like not being able to get a smartphone that’s an iPhone or Android. Another phone might work perfectly well, but you won’t be able to get as many apps.

Right now, researchers perform Ebola experiments on guinea pigs, hamsters, and monkeys. Experimental drugs and vaccines for Ebola will always have to be tested in monkeys before they’re tested in people because monkeys are so much more like people, biologically, than other animals are. Before they make it to monkeys, however, it would help if researchers could test Ebola treatments in mice instead of guinea pigs and hamsters.

Outside of Ebola research, lab mice are much more popular in experiments than hamsters and guinea pigs, which means scientists know more about how mice biology works. The entire mouse genome has been sequenced. People have developed genetic and other biology tools that work specifically in mice. Not being able to do studies in mice is like not being able to get a smartphone that’s an iPhone or Android. Another phone might work perfectly fine, but you won’t be able to get as many apps.

These mice likely won’t directly contribute to controlling the outbreak that’s ongoing in West Africa, says Michael Katze, a biologist at the University of Washington who worked with Rasmussen on the mouse-making team. Mouse experiments are for early-stage treatments and basic science, stuff that’s too near the start of the pipeline to make a difference for years yet. Still, the team hopes its work will help us toward a deeper understanding of Ebola in the future.

Rasmussen, Katze, and their colleagues published their work today in the journal Science.