The future of breweries looked dim on January 16, 1919, when the Eighteenth Amendment and the accompanying Volstead Act banned the manufacture, sale, and transportation of intoxicating beverages. Unsurprisingly, the black market was more than happy to help people drink without getting caught.

Popular Science had some ideas too.

Click to launch the photo gallery.

Despite the Progressives’ intention to improve society by banning liquor, Prohibition became an era characterized by seedy glamor and organized crime. Between 1920 and 1933, we filled our pages with panicked headlines: “Poisons….Lurk in Bootleg Booze,” so naturally, “Millions of Americans Are Committing Slow Suicide.”

We weren’t exaggerating — thanks to the carelessness of bootleggers, thousands of people died after drinking liquor that contained traces of wood alcohol. Still, while the moonshine market certainly enabled social corruption, we’d argue that it also contributed to science by producing an unlikely breed of chemists and inventors.

Contrary to its depiction in pop culture, smuggling wasn’t just about joining the Mafia or running down Prohibition agents. Over time, bootlegging groups mastered formulas for manufacturing large (toxin-free) quantities of raw alcohol, while people running booze between Canada and Detroit invented contraptions that let them transport cases of the stuff undetected. Even certified scientists had fun getting around the law: noting that the amendment banned alcoholic drinks, but not solids, Dr. John C. Olsen, a Brooklyn chemist, cooked up “jellied cocktails” in his lab.

On the less illicit side of things, home-brewing became a popular pastime after the government permitted people to brew beverages measuring 0.5 percent alcohol. After examining the era through the lens of our archives, we’re proud to report that Popular Science taught readers how to appease their vices without dying or getting arrested.

Click through our gallery to learn more about the science of bootlegging and home brews.

The Future of Breweries: February 1919

At the dawn of the Prohibition, brewers were faced with the uneasy task of transitioning into new enterprises. “Machinery costing millions will have to go to the scrap-heap unless ingenuity, guided by the expert advice of the industrial chemist, can find a way out,” we wrote, just one month after the Eighteenth Amendment’s ratification. The task was daunting and expensive, but not impossible. With the help of chemists, and the purchase of mechanisms such as vacuum pans, breweries could modify their beer cookers into equipment used to convert barley into malt sugar. Beer-brewing machines were also perfect for manufacturing soft drinks, which surged in popularity after the Prohibition went into effect in 1920. Read the full story in “What Will Breweries Do?”

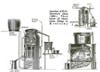

Do-It-Yourself Distilleries: February 1920

Right after the Amendment went into effect, we published a short history of homemade distilleries with the disclaimer that copying these machines would get readers into trouble. “With the orchestra playing soft, soft music, turn back through these pages, look for the past time at all the pretty stills, and–forget stills; forget them for good. It’s all they’ll let you do.” While machines like the ones pictured left hardly counted as a fully-operating distillery, the law prohibited people from even owning a experimental stills. Of course, thirsty inventors saw the Prohibition as an opportunity for innovation. Moonshiners cobbled together tomato cans, funnels, and tea-kettles in order to get their fix. We can only guess whether these diagrams inadvertently helped readers follow suit. Read the full story in “Within the Law”

How to Get Buzzed Without Booze: June 1920

The Prohibition marked a heightened interest in novelty, non-alcoholic drinks: with the aid of refurbished breweries, manufacturers produced ginger ale and soft drinks en masse. Since carbonation couldn’t quite replicate the buzz of alcohol, one inventor went a step further and experimented with sending gentle electric currents through water. To feel the charge, people would drink from a metal cup connected to an electrical coil with a wire. Touching a kitchen stove with their feet would complete the circuit and unleash the “kick.” Curiously enough, this trendy Prohibition drink didn’t hold up over time. Read the full story in “A Glass of Water with a Kick”

PopSci’s Guide to Home-Brewing: January 1921

The Volstead Act defined “intoxicating liquors” as beverages containing more than 0.5 percent alcohol. While people were banned from manufacturing hard liquor, Section 29 of the Act permitted them to make wine and other fruit ciders at home. As you can imagine, brewing permissibly alcoholic drinks at home become one of the era’s most popular pastimes. We recommended a Balling saccharimeter, like the one pictured left, which read alcoholic content by measuring how much sugar was converted in the brewing process. Meanwhile, chemists devised new methods and developed more sophisticated instruments, like an easy-to-use ebulliometer, for testing “near-beers.” For people who weren’t so savvy with lab instruments, we suggested the following on-the-go method: Pour twenty-five drops of Tabasco sauce into a glass of near-beer, drink up, and send a thank-you note to our editor. Read the full story in “Measuring the Home-Brew Kick: Various methods of keeping within the Eighteenth Amendment”

The Secret Equipment of Rum Smugglers: November 1926

During the Prohibition, the once-innocuous areas between Cape May, N.J., Cape Cod, M.A., and the Gulf Ports became hot spots for smuggling. To evade the Coast Guard, bootleggers developed all kinds of gadgets for transporting their wares across “Rum Row.” Dummy smokestacks would hide liquor on otherwise legitimate vessels. Speedboats would tug strings of alcohol-filled tanks into secret coves, while fishing schooners used nets to lug around gallons of booze. Read the full story in “Amazing Tricks of Rum-Runners”

Menacing Moonshine: April 1927

Since prohibition laws were weakly enforced, people could easily acquire bootleg alcohol, which often contained hidden poisons. With the help of chemists and medical professionals, our investigation highlighted the careless process by which untrained chemists created drinkable gin. To curb the distribution of alcohol, the government would poison industrial alcohol with wood alcohol. Bootleggers would then re-distill and redistribute the substance as hooch, but more often than not, traces of poison would cause blindness, nausea, and muscular problems in unassuming customers. Once death by denatured alcohol became common knowledge, however, people accused the government of using illnesses to enforce abstinence. Faced with the increasing discontentment with Prohibition, Government chemists struggled to create a safer, yet equally effective formula for denaturing alcohol. Read the full story in “The Truth About Poison Liquor”

A New Use for X-Rays: August 1927

Bootleggers weren’t the only ones with tricks up their sleeves. George Contreras, Chief Prohibition Agent of LA County, used a portable X-ray machine to detect bottles of whiskey disguised as bales of hay. This photo depicts one man holding the the equipment, which was made specifically for Contreras by an X-ray specialist, while another agent inspects their discovery on a fluoroscope screen. Read the full story in “X-Rays Ferret Out Rum”

The Doctors Debate: August 1927

Eight years into the Prohibition, we still weren’t sure whether the movement actually improved people’s well-being, so we invited a pair of reputable doctors to write for and against the consumption of alcohol. Dr. Haven Emerson, former Health Commissioner of New York City, argued that alcohol is totally unnecessary for human development and can cause brain injuries. Dr. Charles A.L. Reed, former president of the American Medical Association, claimed that moderate quantities of alcohol facilitated tissue formation, and that banning alcohol inadvertently caused the deaths of 65,000 people who drank poisoned liquor. The futures that both men foresaw as a consequence of Prohibition appear above their names. On a more hopeful note, Professor Donald C. Stockberger of M.I.T. is also pictured demonstrating his “spectroscopic apparatus,” which used ultraviolet rays to test liquor for poison. Read the full story in “Prohibition – Is It Good for Us?”

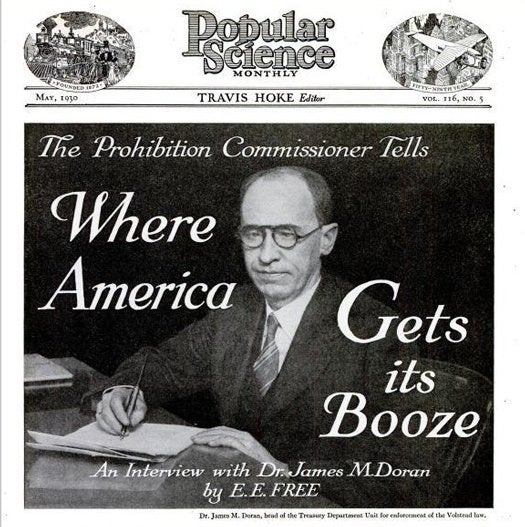

Where America Gets Its Booze: May 1930

After ten years of Prohibition, the bootlegging business entered a new stage of enterprise. Dr. James Doran, head of the Treasury Department Unit for enforcement of the Volstead law, insisted that bootleggers had transited from reconditioning denatured alcohol into fermenting sugar with yeast, and then distilling the substance, to create raw liquor. The previous method, while quick, was so expensive that bootleggers learned to ferment vast amounts of sugar, potatoes, fruits and grains by themselves. Flavoring the raw, diluted alcohol with chemicals and plant extracts made the final product taste like Scotch or absinthe. While the previous era of smuggling was dominated by “rum runners,” by 1930, bootlegging had become much more organized, and could thus hire the best specialists in chemistry, distillation, and machinery to keep business booming. Read the full story in “Where America Gets Its Booze”

Liquor Lurks Beneath the Detroit River: March 1932

Thanks to its shared border with Canada, the Detroit River was notoriously hard to control. Historians estimate that up to 75 percent of the alcohol consumed in the United States during the Prohibition was transported by ordinary people (not just gangsters!) between Windsor, Canada, and Detroit. One of the more elaborate bootlegging devices was an cable tunnel that ferried submarine “torpedoes” filled with alcohol across the river. While customs guards focused on people smuggling alcohol under their clothes, this ingenious contraption quietly reeled in forty cases of liquor an hour. Read the full story in “Underwater Cable Brings in Booze”

The Magic of Beer-Making: June 1933

After seeing how Prohibition contributed to the rise of organized crime and government spending, people were eager to see the amendment repealed. In 1933, the dream came true, breweries sprang back into business and American lager took over the beer market. After thirteen years of explaining how to brew or enhance near-beer, we were more than happy to show our readers how (now legitimate) manufacturers were able to concoct the beverage they loved, missed, and secretly squirreled away over the past decade. Read the full story in “Beer Making Is Marvel of Industrial Chemistry”