1. The baby girl was cured with standard anti-retroviral drugs.

When the baby was born in a Mississippi hospital in 2010, pediatric specialist Hannah Gay began treating her with three anti-retroviral drugs just 31 hours after she was born. This combination treatment has been around since the mid-1990s, and remains the biggest breakthrough in the fight against a disease that has claimed tens of millions of lives over the past few decades. As long as people keep taking the treatment cocktail, the virus remains virtually undetectable (a level of about 50 copies of the virus in a milliliter of blood).

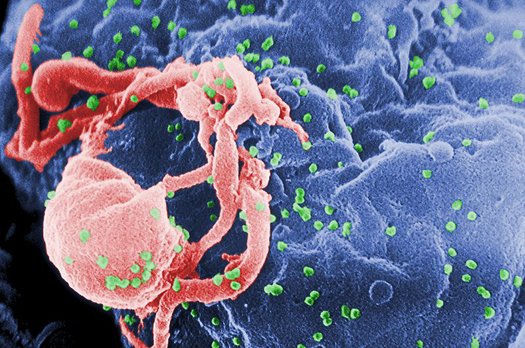

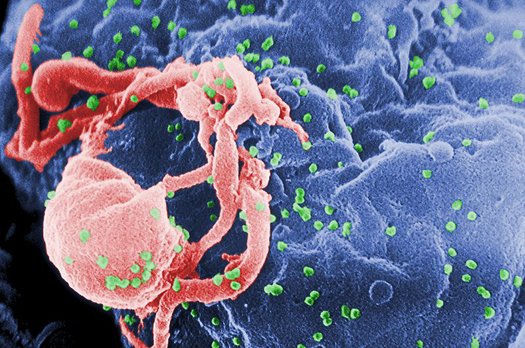

But one of the things that makes HIV so heinous is that the virus can remain dormant in a person’s DNA indefinitely. It insinuates itself in the body’s immune cells and then lurks there silently until some stress on the body–a minor cold, a long week at work–calls the immune cells up to active duty. Then the virus springs back into action, replicating and evolving and infecting other cells. Usually, when an infected individual stops taking the combination drug therapy, their so-called viral load rebounds with a vengeance.

This little girl is the only known exception to that rule: her mother stopped taking her to the pediatrician eighteen months after she was born, and when Gay caught back up with the family, the mother said she hadn’t given the medication to her daughter for six or seven months. Astoundingly, when Gay tested the little girl, she found no trace of the virus. Further tests by doctors all over the country have confirmed those results.

2. Doctors are calling this a “functional cure” rather than a complete cure.

Though the little girl’s viral load has remained undetectable, a couple of tests have turned up fragments of the HIV in her blood. Since the virus does not appear to be replicating, but hasn’t been completely eradicated, researchers refer to the case as a “functional cure.”

3. The newly-reported case is potentially game-changing for treating babies born with HIV.

In the U.S., HIV is rarely transmitted between a woman and her baby. That’s because, when an HIV-infected woman becomes pregnant, her doctors make sure she takes anti-retroviral drugs throughout her pregnancy, and the baby is delivered by caesarean section (in this case, the mother did not seek pre-natal care, and wasn’t taking the medication during the early stages of her pregnancy).

But in the developing world, where access to medical care and expensive drug therapies is limited, some 330,000 babies are born with HIV each year. If researchers can prove that early treatment can provide the same level of cure to other babies, it will be a major step toward reducing the levels of HIV and AIDS in children in other parts of the world.

4. Anti-retroviral drugs are unlikely to provide a functional cure for individuals infected later in life.

Researchers don’t understand exactly why the standard drug treatment worked as well as it did for this little girl, but they suspect it has something to do with how immediately she was treated–that is, after all, the only apparent difference between her case and the millions of other HIV patients currently taking anti-retroviral medications. If that’s true, researchers don’t expect this case to provide many clues for curing HIV/AIDS in individuals who contract the disease later in life.

5. The only other known case of a person being cured of HIV was very different from this one.

In 2007, a man named Timothy Brown–and famously known as the “Berlin patient”–was cured of HIV after receiving a bone marrow transplant that replaced his immune stem cells with cells from a compatible donor who carried a natural resistance to HIV. The new immune cells fought off and killed the virus in his body without becoming infected.

Though the treatment worked, bone marrow transplants are much too risky for most HIV patients to undergo–there’s a fairly high chance the body will reject the donated blood marrow and begin waging an all-out war against its own transplanted immune system. Brown’s doctors took that risk only because Brown needed a blood marrow transplant anyway–he was fighting a losing battle against leukemia, and the doctor’s best hope was to kill off Brown’s cancerous immune cells with chemotherapy before transplanting new immune stem cells from a healthy donor.

The result was a “sterilizing cure”: doctors have not been able to find a single trace of the virus in Brown’s blood since a few months after the operation. Though the blood marrow transplant is too dangerous to provide a feasible cure for others, researchers are investigating ways of engineering a person’s own immune cells to make them resistant to HIV.