Scrolling through Twitter on Wednesday evening, I came across a Reuters article about a Parisian zoo’s mysterious new resident: A mysterious “blob” with 720 sexes that “looks like a fungus but acts like an animal.” I was confused, because the blob was not at all mysterious. The photo clearly showed a slime mold. In fact, the photo caption even said it was Physarum polycephalum. That’s not even a new slime mold. It’s actually, like, the most pedestrian of all the slime molds.

I’m not the first person to point this out (you can literally just Google the species name to read all about it, so the barrier to entry on this one is pretty low) but I may be the most offended. That is why I, Rachel Feltman, lover of sexually-confused blobs and protist enthusiast extraordinaire, have logged on to give this organism the introduction it deserves.

What the heck is a slime mold?

Once considered part of the fungal kingdom, slime molds have slithered into the realm of Protista, which is kind of a kingdom of convenience—the group includes any eukaryotic organism (read: not bacteria or archaea) that’s not an animal, plant, or fungus. This motley crew of weirdos don’t share a common ancestor, and the slime mold’s placement there is a testament to its weirdness.

A mold, of course, is a fungi. But a slime mold is not a mold, and it’s most decidedly not fungal (though it was once mistakenly lumped in with the shrooms, hence its name). Unlike fungi, slime molds can move (yes, really—more on that later) and they don’t have chitin in their cell walls. They also hunt down and ingest food in the form of yeast, bacteria, dead plants, and fungi, whereas fungal organisms essentially use enzymes to digest things down into chemicals that they then absorb.

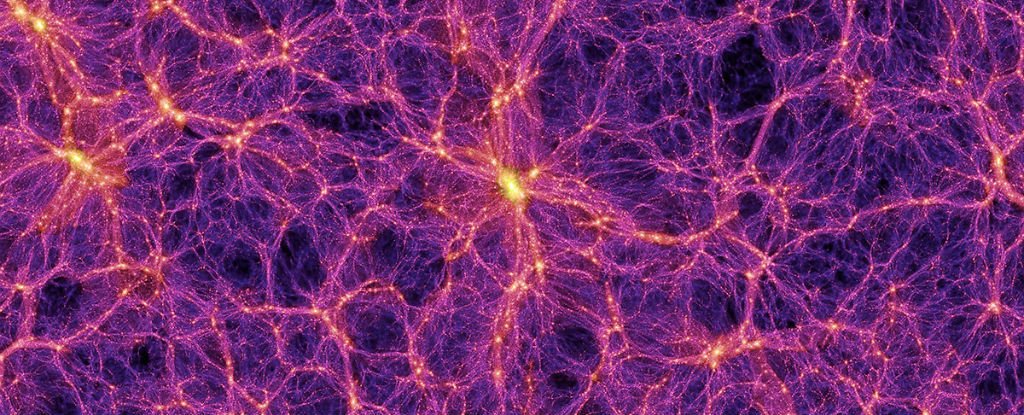

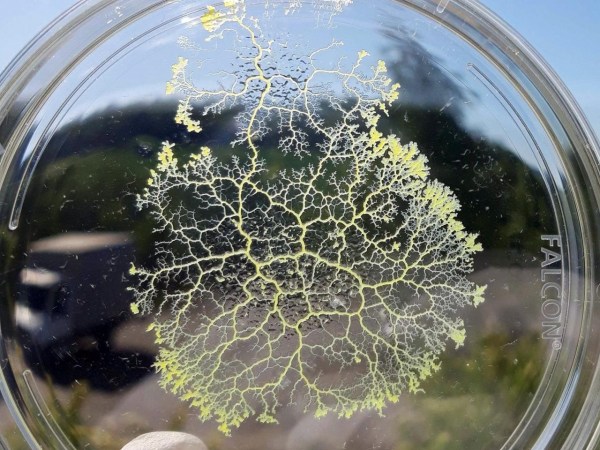

Slime molds are single-celled organisms, but some of them can mate and form structures called plasmodia—that’s what we’re seeing when we look at the giant yellow blob in question. Intriguingly, these large structures are still technically just individual cells. They form many nuclei, but they’re all just floating in the same intracellular matrix, and they divide in perfect synchronization. It’s kind of beautiful, if you like self-propagating blobs of yellow slime.

What’s so creepy about the slime mold blob?

The pun is absolutely intended.

Physarum polycephalum translates to “many-headed slime” (which I find deeply relatable), referring to the behavior of the plasmodiums described above. If you physically separate that single cell into distinct pieces, the nuclei within will endeavor to reconnect—sort of like how, if you get a big gash in your skin, your body isn’t just, like, “oh okay I guess our skin has a big gap there now.” Really, though, this super-quick healing ability is less like healing and more like being able to drop your arm and then pick it back up and pop it on, Mr. Potato-Head-style.

But none of this would be possible if slime molds stayed stationary. Fungi can sort of move by growing out massive, branching pathways of mycelium and sprouting new fruiting bodies (aka mushrooms) in new locations, and plants can bend to and fro in response to stimuli like light or touch. Slime molds are in a league of their own.

Physarum polycephalum moves around by pulsating, circulating water through its one enormous cell to push calcium back and forth through the organism. That calcium triggers contractions in the outer cell walls, perpetuating a cycle of pulsing and squeezing referred to as shuttle streaming. It’s a slower process than walking, but the shape-shifting goo moves quickly enough that you’ll see it happen if you watch closely for a few minutes (or in a high-speed video like the one above). And unlike true fungi, they don’t sit idly waiting for food to come to them. They “forage” by branching out in fractal patterns, using their undulating little arms to find and surround any digestibles.

Are slime molds intelligent?

Don’t expect the blob to take over your local zoo and demand fealty, but these organisms do show evidence of the kind of abilities we recognize as intelligence in insects. For starters, they’re great at certain kinds of math problems: You can put them in a maze, and they’ll find the shortest path to food. Similarly, they’ll shape their movement around obstacles (like salt, which they don’t like) to favor efficient paths to tasty treets.

But it gets weirder: According to some recent research, Physarum polycephalum can learn. In one set of experiments, researchers kept placing slime molds next to food blocked by bitter but harmless substances; after a few days, they’d figured out they could shuttle right over streams of caffeine they’d once refused to cross, and they recalled this new trick even after several days without practice. The researchers even saw them retaining similar knowledge after a hibernation period they spent dried up and inactive, and it’s possible they can “teach” what they’ve learned to other chunks of slime. They’re also great at urban planning and matters of foreign policy.

It’s not clear how this works without anything we’d recognize as a nervous system, so slime mold research is really booming.

It’s not clear how this works without anything we’d recognize as a nervous system, so slime mold research is really booming.

Does the slime mold really have 720 sexes?

Well, this slime mold definitely has more than two sexes, and it may have several hundred. But that’s not at all surprising!

First, consider what we mean when we say “sex”: While the term has gotten tangled up in a lot of cultural nonsense and is further complicated by how little we actually know about sexual reproduction, an organism is one sex or another depending on what sex cells they produce. Organisms that produce sex cells do so in order to combine them with ones from other individuals so the resulting mix will have a new cocktail of genes. This isn’t always the best way to reproduce, but it does mean that there’s more genetic diversity in the species, which makes it more resilient to diseases or environmental changes that might knock out individuals with (or without) particular genes.

In humans, sex is roughly divided in two; most people have bodies designed to either produce and ejaculate sperm cells, or to produce and gestate egg cells. Other species get a lot more options on the drop-down menu of life.

Slime molds, for example, grow stalks and release spores packed with sex cells carrying three variable genes. So they have three sexes, right? Nope! Every sexually mature slime carries two copies of each gene, and each one of those genes can come in a variety of slightly-different flavors. All of the possible combinations add up to hundreds and hundreds of possible sexes. Just like in humans, slime molds have to do the deed (read: drop spores) on an organism that has different variants than their own, so the distinction does matter—but in a much more complex and interesting way than “males” only being able to make babies with “females.”

If you think that’s impressive, check out this mushroom with more than 23,000 possible sexes.