Duolingo, the popular language-learning app, is adding Haitian Creole as a new course on Feb. 22. To accompany the launch, the tech platform is also partnering with Haitian-run restaurants across the US to promote the course.

“Haitian Creole is here in the US. It’s this huge language. It’s the third most spoken language in Miami after English and Spanish,” says Cindy Blanco, senior learning scientist at Duolingo. “We’re encouraging learners to use Haitian Creole in those restaurants. Part of this motivation is to make sure that we’re connecting language with culture and with community.”

Duolingo, created by computer scientists at Carnegie Mellon University, combines language learning with technology, incorporating techniques like machine learning, for example. The Pittsburgh-based tech unicorn (a name given to startup companies valued at more than $1 billion) was first launched in 2012 and went public in 2021. Known in pop culture for its slightly unhinged mascot, Duolingo, along with several other language learning apps, saw a huge surge in downloads during the pandemic.

To develop the content for the lessons, Duolingo worked with linguists like Nicolas André from Florida International University.

“Our Haitian Creole team decides on the vocabulary that we need to teach in a lesson, the grammar that you’ll need,” says Blanco. “Then they come up with the phrases and words and sentences to do that teaching.”

Unique challenges came with this, because Haitian Creole is historically a spoken language with few explicit writing, spelling, and grammar rules.

“There was a lot of figuring out what we want to present to our learners when actually Haitian Creole speakers themselves may not all feel the same way about what is the accepted spelling, what actually is the best way to say this sentence or this idea,” Blanco says. “For many languages like Spanish and French there are actually formal organizations that do this. There’s now one for Haitian Creole as well, so our team relied a lot on these developing standards for the language.”

Haitian Creole is the first of several new languages that Duolingo is planning to add this year. Currently, they have over 104 courses in 41 languages.

“It’s never enough for us. There are over 7,000 languages around the world and we’re at 41. There’s a lot more,” says Blanco. “We wish we could teach them all.”

How Duolingo creates a language experience

To carve out the language experiences on the app, Blanco, who has a background in teaching languages, is tasked with figuring out how to combine what the team knows about language learning and language teaching with what they know about how people interact with and navigate apps and mobile technology.

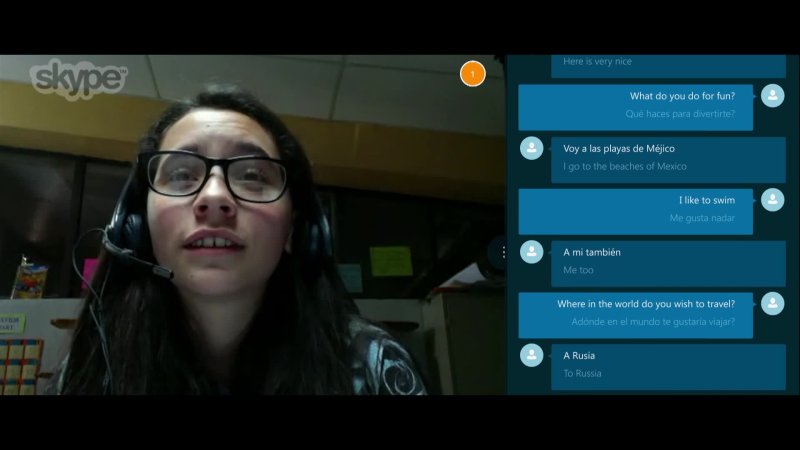

Although a language learning app doesn’t provide the same experience as becoming immersed in a foreign country, Duolingo has tried to make its interface fun and interactive, so users are likely to return to it, where they’ll be able to pick up where they left off. On the home tab, there’s a series of skill quizzes that users can progress through, and there are also tabs for audio lessons, stories for reading and listening comprehension, and a scoreboard to compare your progress with those of other users.

“The tech we have is actually really flexible. As long as we give the right information, it can pull from our lessons, sentences and vocabulary and things to create a lesson,” says Blanco. The machine learning algorithm they have can also track the content and exercises users are processing through to tweak what they see next. For example, if a user is doing particularly well with a concept, the algorithm might trigger more difficult exercises earlier.

In general, the designs of different language courses share common structures. “If you’re a very beginner learner, what do we want you to be able to do with this language after finishing this unit? And that may be things like describing yourself, talking about your family, asking for directions, ordering in a restaurant,” says Blanco. “We start with those communication goals, and often, those will be the same across languages.”

For each of these goals, the team thinks about the vocabulary and grammar that’s needed to get that goal accomplished. And that’s where things can diverge. “Maybe there’s some structure that you’ll encounter much earlier in a Spanish course than in a French course, depending on how difficult the grammar is or what order you want to put these communicative goals,” Blanco explains. “The exact vocab and grammar could vary a whole lot. It’s really a matter of puzzling out what order we teach in to hit all of these communication goals.”

How language learning factors in

The way learning works on the app is both similar and different to how children pick up new languages. One of the similarities is the idea of exposure and input. “You need lots of experience in doing things with the language,” Blanco says. This is easy for kids who hear how the language is used at home and at school by adults, family, and friends.

“It is really hard for grownups. That’s also motivated some of the development of the app,” she notes. “We know exposure and input is really important. So we’ve tried to make it really fun and easy to get back into the language so you can do it for 5 minutes on your commute, you can do it just before going to bed, you don’t need to block out this hour of classroom time.”

In addition to exposure, Duolingo will also start users on “receptive” exercises, where users are receiving the new language, but don’t have to respond yet. And as they continue to work through the lessons, they’ll get more “productive” exercises where they have to write out translations and responses or speak the words.

The tech not only grades users but can rate how difficult different exercises are and use that to determine the order of lessons throughout the experience.

“There’s some general things we know about difficulty that are true across the board. Receptive [exercises], translating to English, that’s going to be easier for everybody,” Blanco says. “But based on your personal pattern of mistakes and errors, it figures out what exercises have been tricky for you, what vocabulary and grammar you have more difficulty with, and we can personalize based on your particular learning pattern.”

Another characteristic they borrowed from how kids learn is something they call implicit teaching. This is the idea that not every single word in a sentence needs to be translated and memorized, and that as users engage with the content, and the lessons, they will start to notice the order of words in the sentences and deduce how the grammar works in each context.

[Related: MIT scientists taught robots how to sabotage each other]

“There’s just no way we can make the adult experience as efficient as it is for kids. Kids have no jobs, they have tons of time, they have lots and lots of people around them,” says Blanco. “For adults, we’ll never be able to create that experience. But there are things we can do to speed it up.”

That’s by pairing implicit learning with more explicit instructions, corrections, or feedback. “In our bigger courses, like the French course, you’ll get more tips and information about different kinds of mistakes,” Blanco says. “We know implicit gets you to learn more types of information, but we know that we need to supplement.” The algorithm helps set how often these explicit comments appear, and on which errors. For example, it can discern between a simple typo with a bigger grammar issue.

What Duolingo is working on

Blanco thinks that a lot of new tech developments have made challenges like speech recognition easier. But the model they use is different from a typical language model. “Part of it is because our use case is really different from technology that might be used in customer service chat apps,” she says, since Duolingo’s users are inherently not proficient native speakers of the languages they’re choosing to learn. “Customer service chats are looking for particular keywords, but they’re also expecting certain kinds of phrasing and grammar.” Their algorithm expects certain types of errors.

It’s a work in progress. The team is experimenting with moving the tech away from just translating, even though that’s more easy computationally to do.

“I feel the next frontier for us in effective language teaching is what we do with open ended speech and open ended questions,” she says.