The modern Olympics have been running for 116 years, but many events remain unsafe and difficult to score. We propose ideas that might help solve some of the toughest problems.

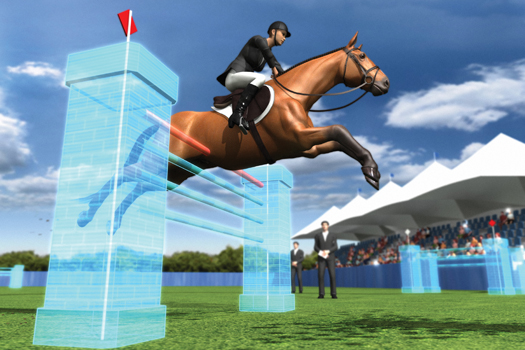

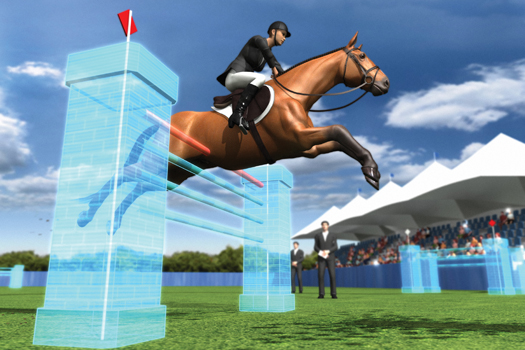

HOLOGRAPHIC OBSTACLES

About 100 riders are injured in eventing falls every year, and when a multimillion-dollar horse goes down, even a minor injury like a twisted ankle can end its career. Computerized bases on the ground could project holographic obstacles, such as four-foot fences and 15-foot-wide pools, in place of dangerous physical objects. Line-of-sight infrared beams could monitor the edges of the obstacles; if the horse breaks the beam, the system would instantly alert the judges—and the crowd—to the fault.

SMART LANDING PADS

Scoring the exact length of a long or triple jump can be imprecise and time-consuming. Athletes land in a sand pit, where they make several marks; officials must locate the mark closest to the takeoff line before they can measure. Researchers at Arizona State University have developed a 2,016-pressure-sensor array to map where an athlete hits the ground. Placed underneath the sand in the landing pit, a dozen or so of the mats could record the exact point of touchdown, and a computer could automatically calculate the length of the jump.

HEAD-UP GOGGLES

Swimmers are often unaware of their standing in a race until it’s over. Goggles with an integrated head-up display could broadcast a live view of the competition and help racers to better pace themselves. Waterproofed with an invisible layer of hydrophobic nanoparticles, a technique currently used on cellphones and other gadgets, a small computer tucked in the lower right-hand corner of the goggles would gather position information from other wired racers over Bluetooth and display it on a quarter-inch LCD.

AUTOMATIC GOAL KEEPER

In a low-scoring game like soccer, one bad goal call can do a lot of damage. A reversed call in a match against Germany, for example, cost the U.K. a potentially pivotal goal in the 2010 World Cup. To help refs, who may not always have a clear view of both the ball and net, German research institution Fraunhofer has developed an automated goal-tracking system. Actuators around the net generate a magnetic field across the face of the goal. When the ball passes through that field, a chip embedded in the ball sends a signal to the ref’s watch within one tenth of a second.

RETRACTABLE DIVING BOARD

On a good day, a diver’s head misses the board by a couple of inches. On a bad day, the two collide, as happened to American Chelsea Davis in the 2005 World Championships (she suffered a broken nose and needed several stitches) and, most famously, Greg Louganis in the 1988 Olympics. A hydraulic springboard could make diving safer. In the one second a typical diver is airborne above the plane of the board, it could retract as much as three feet. An accelerometer would sense each takeoff and initiate the movement.

John Brenkus is the host of ESPN Sport Science and the author of The Perfection Point. He lives in Los Angeles.