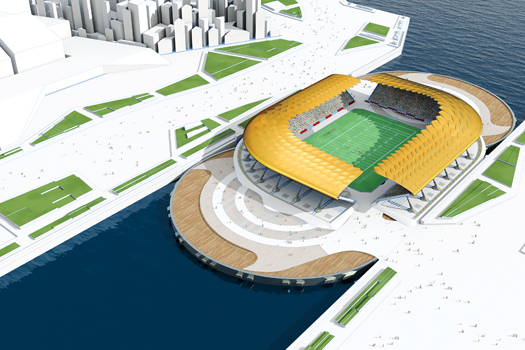

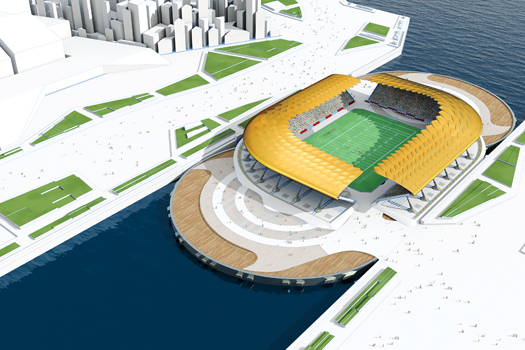

Almost as soon as RFK Stadium opened in 1961, it became clear that the stadium was a dud. Football fans complained that the low seating made it difficult to see the entire field. Baseball fans complained that they had to twist in their seats to see the action at home plate. By trying to accommodate two sports, the stadium failed at both. All dozen of the combination football-baseball stadiums built in the U.S. since then have garnered similar complaints. The only one still in use as a dual-sport venue, the Oakland Coliseum, consistently ranks among fans as one of the worst sports arenas on the continent. Yet despite this dismal record, some architects are considering multi-sport venues again. PopSci asked Greg Sherlock, an architect at Kansas City–based Populous, the world’s leading stadium-design firm, to give us a look at the future. His concept: a truly transformable stadium, whose modular parts snap together like Legos in custom configurations.

TRAVELING VENUES

Building new stadiums for one-time sporting events like the Olympics is almost always a waste of resources. The event spaces China built when it hosted the Summer Games in 2008, for example, now mostly sit empty. Sherlock’s floating stadium could be towed to any city with a waterfront, installed for the event and shipped away afterward.

SWAPPABLE SECTIONS

Stadium managers could use modular seating sections of different shapes to provide the best seating configuration for any event. The seats for football and soccer games would line up along the sidelines and ends of the field, and seats for baseball games would be angled to face the pitcher’s mound.

SEE-THROUGH ROOF

To preserve the outdoor ambience while still protecting fans from inclement weather, a translucent roof made from a type of plastic called ETFE would open in sections. Individual panels would block wind and rain, while louvers would twist to diffuse a blinding sunset or to create better acoustics for a concert.

SUSTAINABLE POWER

Many of today’s stadiums, including the Washington Redskins’ FedEx Field, run partially on electricity generated by photovoltaics, wind or biodiesel (or plan to). But a floating stadium has an additional source of clean energy: underwater turbines or buoys, which would transform the kinetic energy of the tides, river current or waves into electricity.

SELF-CONTAINED TOILETS

Rather than running pipes between barge sections—the pipe interconnects could leak—separate, self-contained barges carrying toilets and other facilities would dock at several locations around the stadium.

MODULAR PLAYING SURFACES

The playing surfaces—a six-inch layer of soil topped with turf for sports such as football and soccer or with a baseball infield, tennis court or other playing field—sit on barges. Movable turf plates aren’t unheard of: The entire football field at the University of Phoenix stadium in Glendale, Arizona, rolls in and out of the arena in one piece.

SEAMLESS JOINTS

Magnetic interlocks could hold the floating panels together within two or three millimeters of each other. To prevent players from tripping on the seam between sections of the field, each plate would be framed with a pressurized silicone gasket that would press up against the neighboring sections and fill the void. Extra soil could then be piled on top for a gapless playing surface.

ELEVATED STANDS

The driving principle behind stadium-seating design is to get spectators as close to the ball as possible. For a big crowd at a football game, a shallow bowl works well, but for a small tennis match, the nosebleed seats should be pulled in closer. Each row of seats rests on standard, lightweight hydraulic lifts that can make entire sections steeper or shallower with the push of a button.