An artificial, working brain smaller than a grain of rice, a heart on a stick the size of a micro SD card, and many more “organ chips” could help doctors peer into the inner workings of the human body. Today DARPA and the FDA announced a new $70 million program called Tissue Chip for Drug Testing, aiming to study the micro-environments of various human organs without ever using a scalpel.

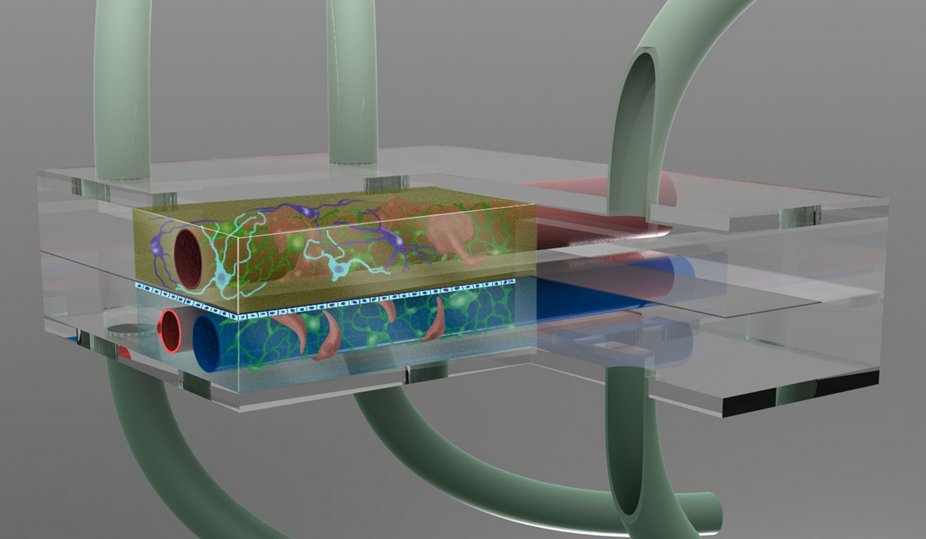

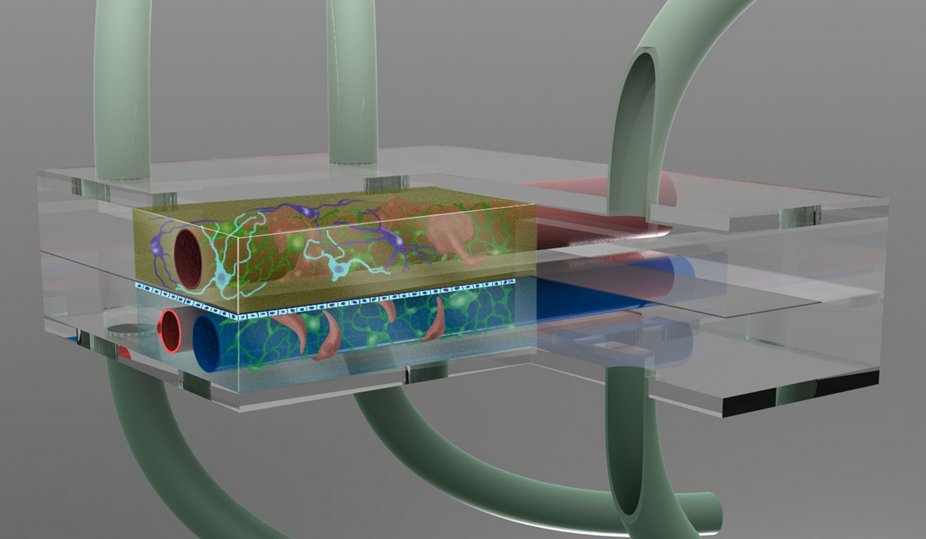

Many types of labs-on-a-chip are already used to study how certain organs or tissues work, and how they might respond to small molecules that could work as new drugs. But they are often limited in scope, allowing studies of certain cell types or fluid types. This project asks scientists to build 10 different organs-on-chips, link them together to mimic the real body, and design software that can automatically control fluid flow and perform analysis.

It would be a nice silicon-based alternative to animal tests, which are controversial and don’t always work anyway — a mouse or a rat can’t emulate the whole spectrum of human diseases and disorders. More than 30 percent of human clinical trials fail because the drugs don’t work in people the way they did in animal tests, according to the National Institutes of Health. This system would be able to test potential human responses to new drugs, and it would be able to weed out toxic ones earlier in the development process than they are now.

The Wyss Institute at Harvard, Vanderbilt University, Cornell University, Johns Hopkins University and the University of California-Berkeley are among the partners in this new project. At Vandy, researchers will endeavor to study the brain and its difficult barriers, which prevent various drugs from crossing into the brain. The trickiest is the blood-brain barrier, which enables certain compounds the brain needs to function, but blocks most everything else, including potentially helpful drugs. A new “microbrain” would study these abilities by combining a sliver of a human brain, a chamber filled with cerebral spinal fluid, and blood vessels, which together would function just like a real brain.

“Development of a brain model that contains neurons and all three barriers between blood, brain and cerebral spinal fluid, using entirely human cells, will represent a fundamental advance in and of itself,” John Wikswo, leader of the project and director of the Vanderbilt Institute for Integrative Biosystems Research and Education, said in a statement.

At Harvard, scientists at the Wyss Institute will build on their previous organ-on-chip research, studying the lungs, heart, intestines and more. The five-year project, which includes 17 separate grants, kicks off today.