The problem is as follows. The perfect winter insulation should be ultra warm, extremely light and packable, and stay warm when wet. No single insulation–not the classic goose down, not the best efforts of synthetic insulation makers–has met all three of those criteria, and folks like hikers, skiers, and snowboarders have had to settle. But North Face claims its newest jacket technology, which uses ball-shaped synthetic insulation that behaves like down, is the perfect compromise.

Goose down has been the preferred insulation for outdoor adventurers and enthusiasts for generations. It’s not only the warmest and lightest insulation, but it feels luxurious to wear–lofted goose down traps warm air while softly conforming to your body’s shape. But down is expensive, and if it gets wet from sweat, melting snow or rain, it becomes matted and loses its insulating properties. Plus, down has to be encased in expensive “down-proof” fabrics that prevent quills from poking through or migrating around the inside of the jacket.

Synthetic insulation, on the other hand, isn’t affected by moisture–it stays warm even if it’s wet–but it’s heavier and less compressible than down. And it’s stiff, comparatively. The long linear fibers of synthetic insulations don’t contour to your body’s curves nearly as well as down, so it’s never managed to achieve the same cozy feel. Synthetic insulation also isn’t as warm for its weight as down. So those battling the winter elements have had to choose: dryness and affordability, or suppleness and warmth?

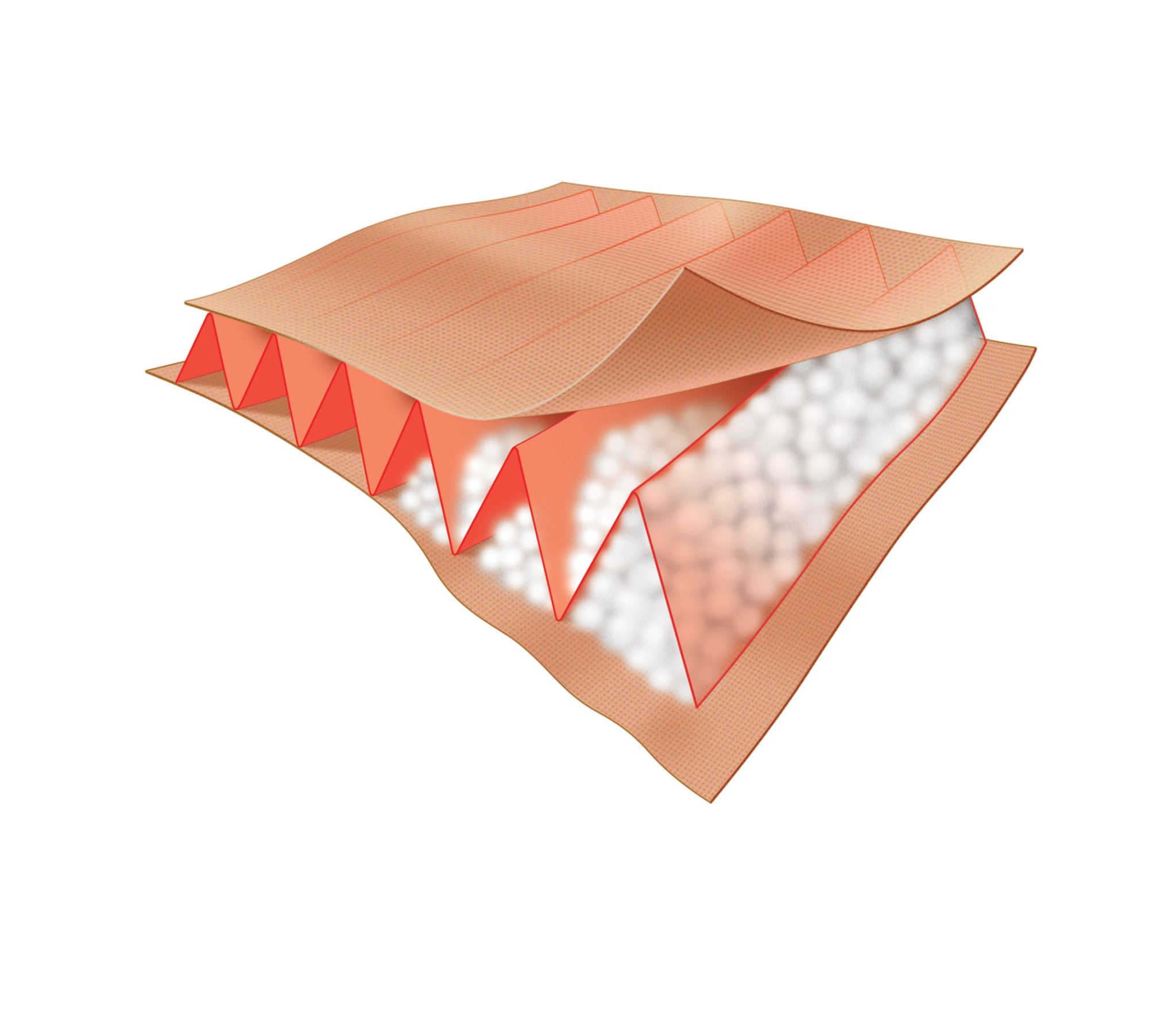

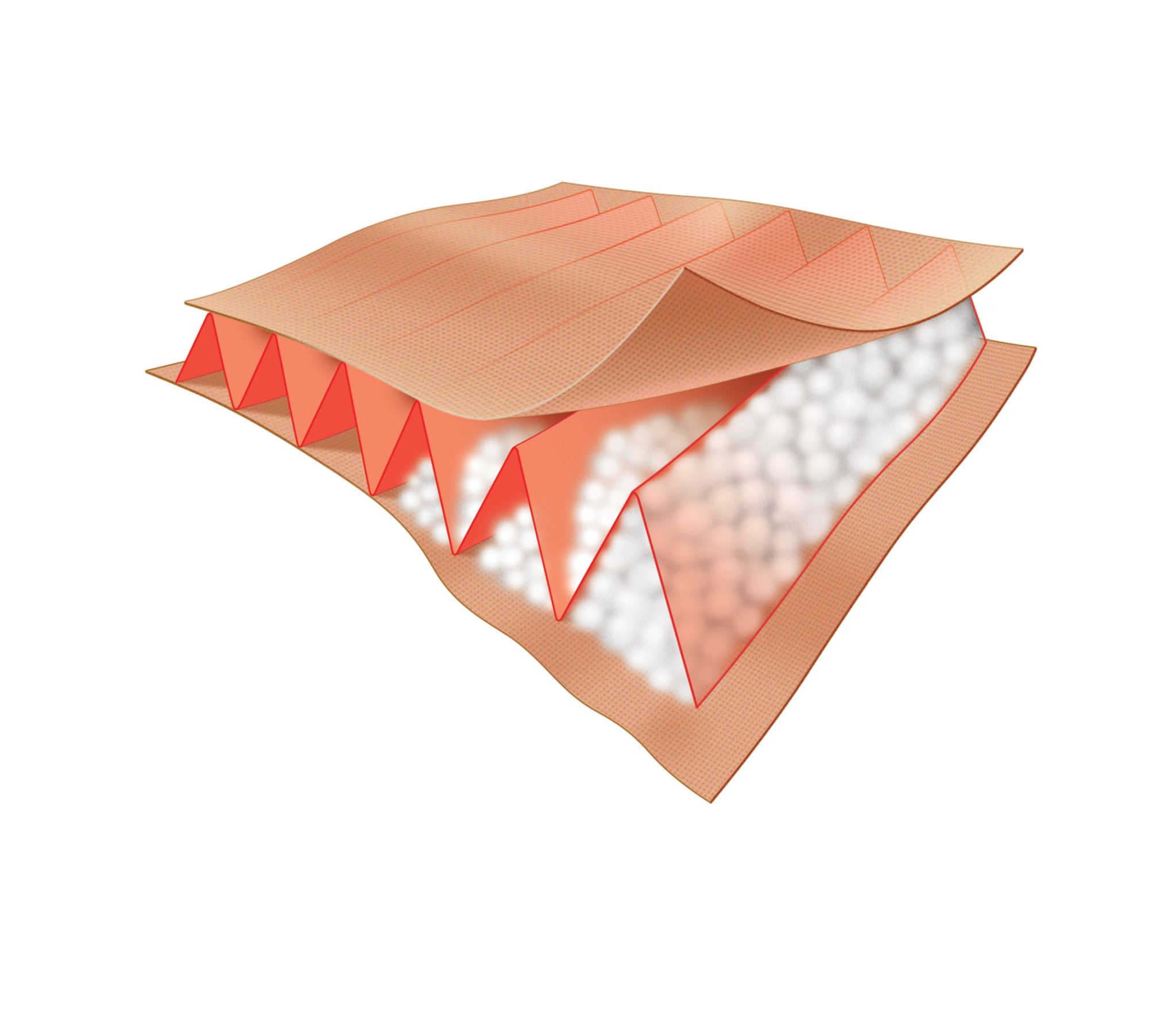

ThermoBall, created by noted outdoors/college campuses company North Face, is a synthetic insulation that closely mimics down. Unlike traditional continuous-filament synthetic insulations, which are laid out in flat sheets comprised of thousands of long filaments, ThermoBall is made from short strands of polyester that have been spun and frayed into millions of fuzzy miniature cotton-ball-like balls, 0.15-0.2 inches in diameter. They float inside hundreds of tiny pockets, or baffles (seen above), sewn into a jacket. They are designed to cluster like feathers, maintaining air pockets (which are key for retaining warmth) rather than clumping together into a solid mass.

Triangular baffles help keep the insulation lofted so it traps body-heated air, where insulation’s “warmth” comes from. Triangular baffles aren’t new, but the ones in the ThermoBall jacket are smaller than any it’s been possible to use with down, since the individual balls in ThermoBall are smaller than each down feather.

The request for a better synthetic came specifically this time from world-renowned mountaineer Conrad Anker and the rest of the North Face climbing team in 2008 after an aborted attempt to climb Mount Meru in India’s Garhwal Himalaya. “We spent two years developing new products that would help us do better on the next attempt,” Anker says. “ThermoBall was one of those products.”

ThermoBall was conceived as a solution to that trip’s shortcomings, and so the team began work in The North Face’s materials lab, hitting the new jacket with a battery of tests ranging from odor retention tests to bombarding the jacket with water to test its hydrophobic coating, as well as lots and lots of abrasion tests to make sure the jacket would stay together and not spew tiny balls of warmth everywhere. After six months of testing, the lab’s designers sent it to their athletes for real world feedback.

“As an athlete tester, I have no idea what I am getting a lot of the time,” said Anker. “The North Face’s designers say, ‘try this and give us your feedback.’ So I do. When I got the first ThermoBall jacket, I noticed it stayed warm even when it got soaked with sweat on a long run,” while staying “soft and comfortable” to wear.

In June, The North Face sent revised and updated versions of ThermoBall with nine athletes to climb Alaska’s Denali. When the team reached base camp, The North Face designers were there to get fresh and immediate feedback from the climbers. Then it was back to the drawing board to further refine the insulation and the ThermoBall jacket. Those refinements mostly focused on the “face” fabric, the outer skin or material that faces the outside world. The original fabric used for the face turned out to be too light, which handicapped the jacket’s warmth. The testing was important not just for extreme climbers, but also for your average, you know, cold person.

“Having the ThermoBall jacket on Meru on our second attempt this fall provided mental comfort,” says Anker. “We didn’t have to worry about our jackets getting wet. When there are three guys sleeping in a portaledge, there is condensation. We slept in these jackets as well as wearing them when we were climbing as part of a five layer system. And they did the job.” Jimmy Chin, Renan Ozturk and Conrad Anker successfully climbed the central pillar of Mount Meru reaching the 20,700-foot summit this October.

So, ThermoBall is designed to feel like down when you’re wearing it—soft and cozy, rather than stiff. It’s comparable to down in weight, and it compresses like down when you need to stuff a ThermoBall jacket into a pack. ThermoBall weighs about the same as down, but North Face claims its ratio of weight to warmth is 15 percent better than the best synthetic material, even though by specific clo ratings (the rating used to measure thermal insulation), down is still superior.

ThermoBall is highly water repellent and warm even if it gets wet. And, because there are no quills to worry about, North Face is able to use a tightly woven fabric with silk-like threads as the inside and outside of the jacket, making it lighter in weight as well.

ThermoBall may not crush those dastardly, incredibly warm geese, but it’s an interesting step forward, and North Face promises that further ThermoBall developments are in store. The biggest problem so far? ThermoBall is still not as warm as down. That’s the main obstacle to this being the ultimate winter jacket tech. But the team is convinced they’ll get there eventually.

NORTH FACE THERMOBALL HOODED JACKET

Release date: July 2012

Features: Pre-cinched hood, cuffs, bottom hem (to keep warm air inside), shoulder panels to resist backpack wear, large zip handwarmer pockets, machine-washable

Price: $280, from The North Face