Four Lessons About Data From Ireland’s Biggest Bookmaker

Got money on the name of the next pope? We spoke with Paddy Power on how predictive data modeling helps set the odds on a huge range of 60,000+ bets per week

At Paddy Power–Ireland’s largest bookmaker–teams of quants and risk analysts set the odds on 12,000 to 15,000 events a week–everything from horse races and other sporting events to speculation on the name of Beyoncé’s unborn child. Within these events, there are 60,000-70,000 individual bets, or “markets,” to be made. And every market needs a set of odds–some kind of calculation of the probability that a specific outcome might occur, based on available data. But how does a bookmaker know what data is good and what data is bad? How can it build safeguards into predictive systems so it doesn’t get burned?

A fundamental tenet of the Data Age is that more data plus more computational power equals a clearer predictive picture of future outcomes. Such prediction models have led to better weather reports, more profitable (and sometimes more dangerous) financial models, enhanced energy exploration, more efficient law enforcement–you name it, someone is crunching the numbers and trying to glimpse what’s coming.

Some of Paddy Power’s events are backed with reams of data with great predictive value, like a racehorse’s performance history and pedigree. Others events are so unique (Beyoncé’s baby name) that, surprise surprise, useful predictive data for them doesn’t even exist.

Whether an event is data-rich or data-poor, the betting public still expects Paddy Power to produce the odds. We dialed up the bookmaker’s Head of Quants Rob Reck and Head of Risk Dermot Golden (a better name for an Irish bookie we are yet to hear) to talk about information bias, the data within the data, and the predictive power of information technology. Here are four lessons we learned about data from two guys who produce a million tiny data-derived updates to their business each and every day.

WHERE YOU GET YOUR DATA MATTERS

Bookmaking is largely about figuring out the likeliest outcome of an event, determining how likely that outcome is, and then building in a cushion for yourself based on your confidence. Data quality is the name of the game, and whether you’re trying to predict which city will have the whitest Christmas or where the next major volcanic eruption will occur (Paddy Power makes odds on both), where you source your data matters.

“If you can get a lot of statistical data that you can analyze, you can get a hell of a lot more out of that than somebody giving you an opinion on when a volcano might erupt,” Golden says. “If we’re doing the number crunching ourselves, it gives us a far greater degree of comfort than listening to three different weather reports based on chaos mathematics and interpretations by three different meteorologists.”

This has everything to do with the kind of outcome you are trying to predict, and whether or not the data you need actually exists.

“If it’s our data, we’re very happy with it,” Reck says. “If it’s a professional body compiling the data we’re generally very happy with it. But sometimes you’re reduced to amateurs or people who just have an interest in something maintaining that data. And you just can’t have huge confidence in that. It’s all you’ve got, but you just can’t have a huge confidence in it.”

That’s another way of saying that outcomes are only as good as their inputs. Better data spells confidence.

DATA GOES WHERE THE MONEY GOES, BEGETTING MORE DATA

“There’s a tradeoff,” Golden says. “You can invest in the data and you can invest in the analytics, but you have to balance against the turnover. During a Rugby World Cup final you’re going to turn over hundreds of thousands [of bets], and on a TV show you’re going to turn over tens of thousands. You have to balance a football match at 3 p.m. on a Saturday afternoon, and “X-Factor” at 8 p.m. on Saturday night. There are far more football traders than novelty traders. So we do far more analysis of football than we do of novelty markets.”

Data, in other words, tends to spring from places where there is some kind of perceived advantage. And often there is an advantage–or at least a perceived advantage–in places where data is already abundant and confidence is high.

“Once it gets down to the nitty-gritty of betting all these tens of thousands of markets, it’s a combination of models and technology. But the big calls are still made by guys sitting there thinking about ‘Will this horse win? Can United win?'”In bookmaking as in the larger world this kind of cycle can be a great thing. Consider the human genome. Once it was finally sequenced and researchers had their first real set of genomic data to work with, innovation began driving breakthroughs that then drove investment that drove more research and data that drove further innovation and further breakthroughs. This cycle is still feeding itself, accelerating as the body of genomic data continues to swell.

But this can also cause data to proliferate unevenly. Humans are generating something like two exabytes of digital data per day on the whole, yet in some places there is a wealth of data (sports statistics for instance) and in other places data is scarce.

THERE’S DATA WITHIN THE DATA

When hard data is scarce, bookmakers have to take what they can get. Sometimes that’s some kind of expert consensus or an averaging of subjective opinions. But they also look to the wisdom of the crowd. For instance, Paddy Power does a tidy business clearing bets on the “American Idol”-like singing competition show “The X-Factor,” in which the audience votes for its favorite acts via text message. And in this case, the data feeding the prediction models is often found in the betting itself.

“When you see the bets coming in and the way the money flows, that’s the same crowd who are actually texting in the votes for these people,” Golden says. “The people placing bets are the same people who are actually interested enough to be texting. So I need to react. I need to access the wisdom of the crowd.”

Which presents another problem–the same source providing the data is also influencing the outcome of the event. But for Paddy Power it’s also a secondary kind of data that affects the outcome of the odds they set. It’s information within the information, and in cases where there’s little hard data to go on–and this is especially true when it comes to subjective, fluid, human-influenced events rather than more rigid, random, or scientific events like earthquakes or the weather–this data within the data can be the most informative thing you have.

“The weaker the data, the more margin you build in,” Golden says. “And then you respect the flow of money, because there’s information in the money. The type of event will tell you the value of that information. If it’s a TV show it’s very valuable. If it’s a volcano erupting, it’s not very valuable. We can price soccer to single figure margins. For something like Beyoncé’s baby’s name, we really don’t know where it’s going. So in those events we’ll keep a really close eye on the money. If a gynecologist living somewhere in L.A. starts making bets on this, we’d get very interested.”

The same is true for something like a presidential election. For such high turnover events, Paddy Power commissions market research in an attempt to get a better handle on what the outcome might be. But sometimes, the Paddy Power line itself can be an influencing factor of public opinion. Says Golden:

“We do a lot of turnover, so a lot of people look to us as a price guide to indicate the probability of somebody getting elected, because we have a pretty good handle of what’s actually happening out there. Again, this is the wisdom of the crowd. There’s information in the prices put up by Paddy Power.”

“The polls are published every three-to-five days, but there’s a Paddy Power price posted every day,” Reck says. “A lot of people start looking at those odds, particularly journalists, and infer from that the probability for any individual candidate.”

When journalists or analysts look to Paddy Power for guidance and include that in their coverage, they can actually prod public opinion toward Paddy Power’s predicted outcome. And of course, when people place their bets and their votes on the same candidate, they are no different than the fans of “The X-Factor” who bet but also text. There’s useful information about voter sentiment and political climate embedded in that data that can inform any future prediction.

TECHNOLOGY CAN ONLY DO WHAT YOU TELL IT TO DO

“We make a massive investment in I.T.,” Reck says. “It’s a very I.T.-intensive business. We tend to all be ex-bankers, so the way we think about technology is the same way they think about it in the financial services sector, in terms of how real-time it has to be and how it supports our business. It’s not just an add-on, it’s integral to what we do.”

But all the predictive algorithms and supercomputers in the world can’t actually see the future. Data is what it is, and there is no golden algorithm that can turn it into a concrete picture of future outcomes.

“Technology can only do what you tell it to do,” Golden says. “It’s really about your ideas and how you interpret the data, and that’s where we believe we’ve been quite good. We’re very, very tied to technology in this organization. So we make a big investment in it, that’s the way we operate.”

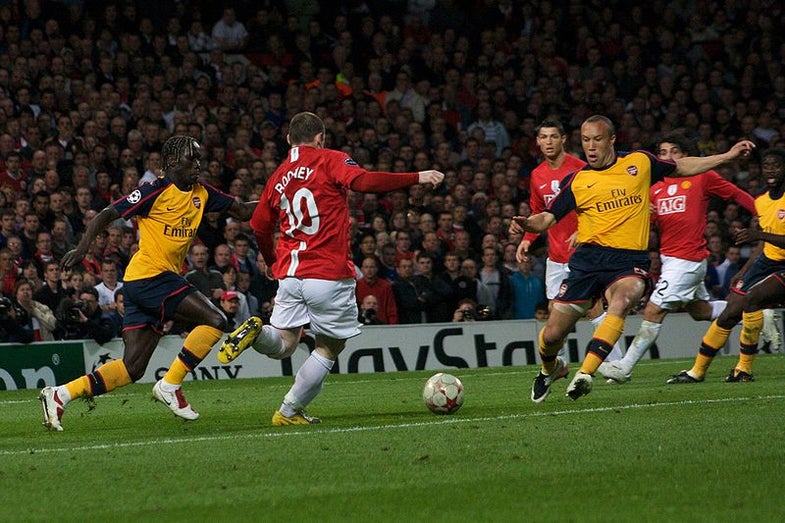

“But the big directional plays are still intuition,” Reck adds. “Once it gets down to the nitty-gritty of betting all these tens of thousands of markets, it’s a combination of models and technology. But the big calls are still made by guys sitting there thinking about ‘Will this horse win? Can United win?’ The big calls are made by individuals. Thousands and thousands and thousands of little calls are made by algorithms and technologies that are able to implement that in real time. A lot of it happens automatically after the guy takes the big view on whether a particular team has a slightly better chance than the market thinks to win a particular match.”

Human decisions are another form of data, in other words, and in the end they are often the most important. Ideas on how best to interpret data and how best to model events are larger drivers than the technology itself, which is often tailored around a set of human inputs. The algorithms can make thousands of tiny decisions in the blink of an eye. But first someone has to tell them to.