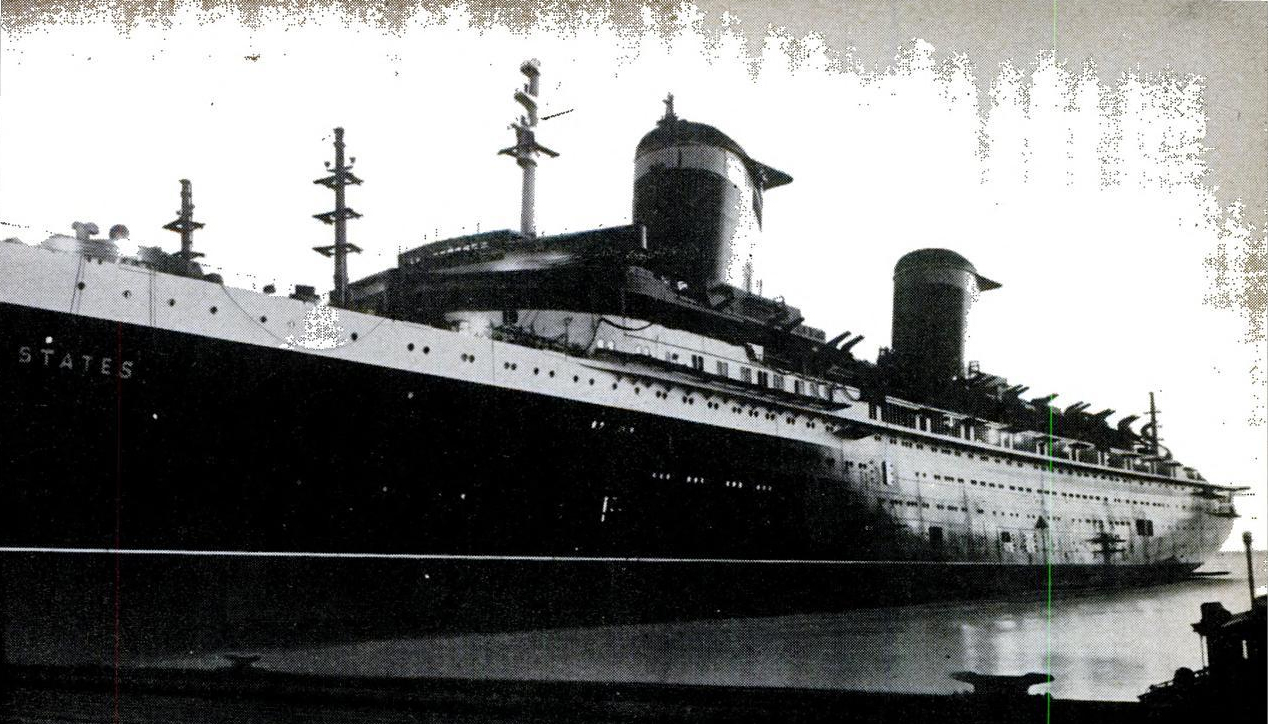

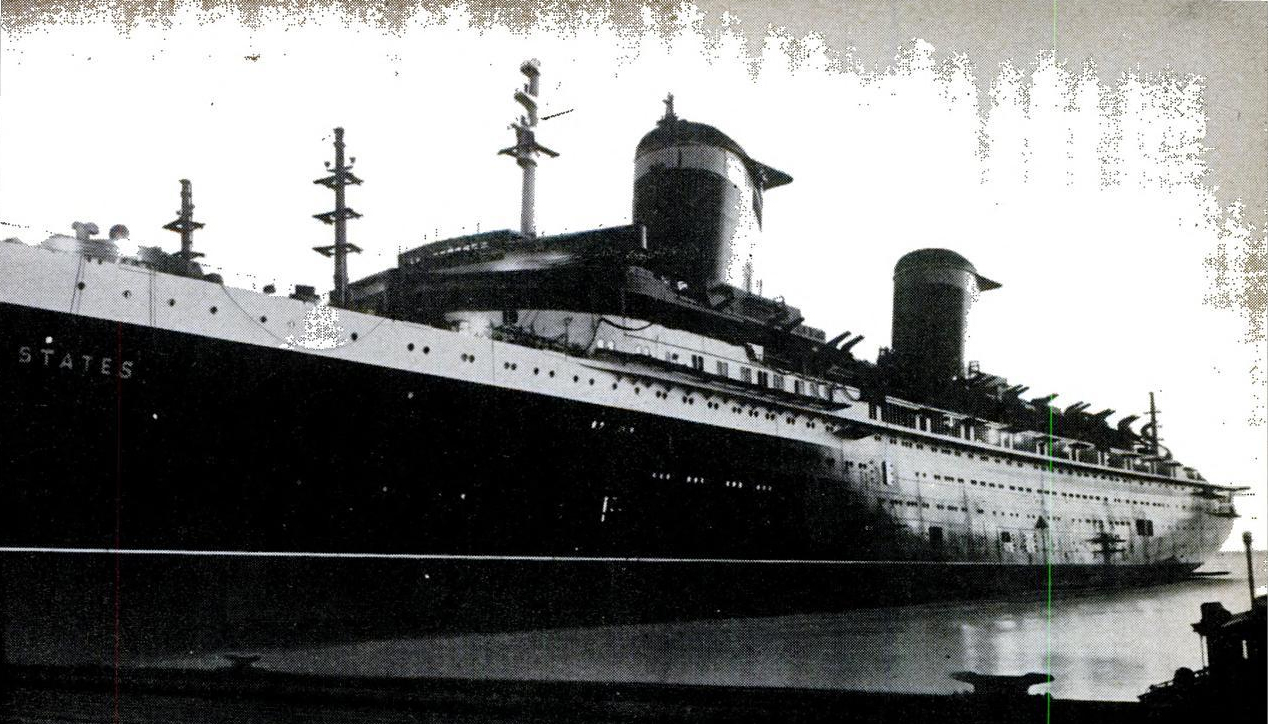

This month the waters of the Atlantic Ocean will feel for the first time the smooth rush of something very special in the way of superliners. The S.S. United States will be taking her builder’s trials and acceptance trials preparatory to entering the deluxe transatlantic trade on July 3.

For the first time in 75 years this country has built a competitor in the top-speed bracket. The entirely mythical “blue riband,” denoting the holder of the record for the fastest passenger ship crossings of the Atlantic, has been in European hands for a century. In a sense this has been a matter of default; American ship operators in recent years have not chosen to enter the competition for many reasons. We have built many fine and popular ships—highly comfortable and of good speed—but not ships designed to travel at the 30-knots-and-above necessary to make record passages and headlines. The United States is definitely in this field.

Beyond that there are other toppers about this ship. She is the largest passenger vessel this country has ever built—51,500 gross tons. Operated by a 1,000-man crew, she will carry more passengers than any other American-built ship—nearly 2,000. She is fireproof beyond any standard ever set by any commercial vessel under any flag. She is air-conditioned throughout—all public rooms, cabins, crew quarters. She uses more aluminum than any other single structure ever built, land or sea. It is used structurally and for decoration and furnishings.

Usually, such technical matters do not strike the eye of the beholder or customer. But those who board the United States for her maiden voyage and for trips thereafter will sense the new qualities. At dockside she shows all the bigness of her 990-foot length, her 10 1/2-foot beam and her 13-story height above the waterline. Yet there is a lightness and easiness about her lines. The bow springs forward not sharply but cleanly and in harmony with the bulk behind it. The white superstructure and the great stacks lie easily on the sleek black hull.

Step aboard this ship and both your eyes and your feet tell you there’s something different about her. On the open decks you expect the “plock” of teak decks underfoot and the feel of teak rails under your hands. But there’s no teak. The decks are a brand-new mastic composition spread over aluminum or steel. The rails are long sections of extruded aluminum, glossy under a special finish. And the decks are remarkably open, swept free of all possible protrusions and fittings, with few ups and downs. The overhead is sheeted smoothly in metal to conceal beams and pipes that would be eyesores.

The same inside. The corridors are long straightaways, with few jogs and turnings and with the usual plumber’s nightmare all out of sight. Many of the public rooms extend the full width of the ship. There are many pieces of art on American themes, some in metal or glass—no wood is used in the ship itself. There are screens of glass sculpted by sandblasting. There is a plaster relief map of the North Atlantic. There are aluminum panels anodized to give them soft colors. There are four-foot sculptures carved out of foam glass.

Furnishings Retard Fire

Fabrics and wall finishes run the whole spectrum, but both fabrics and paints are fire-retardant. Furniture is aluminum; upholstery and cushions are springy and soft but they are filled with a new material that will not flame.

For those who must take their shore side fun to sea with them there are all the facilities. There are two smart theaters for movies and other entertainment. There are swimming pools, lounges, restaurants, nightclubs, libraries, barbershops, beauty parlors, gift shops—all the things that go into a modern luxury liner. There is even a special refrigerated room for the storage of those bon voyage baskets!

For the athletic-minded, there are sports decks—topside, forward and aft—plus a gym and indoor pool. Enclosed promenade decks sweep along the sides. Cabins range from four-in-a-room for tourists to suites up to five rooms in first class. Cabin class—524 passengers—and first class—888 passengers —have private baths; in tourist class—554 passengers—the baths are shared. The cabins have a wide range of color schemes—soft tones and bright, worked out in contrasts, a far cry indeed from the dead whites and “institutional” colors familiar not so long ago.

Can Be Converted into Troop Transport

Despite the ship’s charms for pleasure travelers, she was built with very different auxiliary purposes in mind. In time of war the United States would become a troop transport, capable of carrying a full Army division. Accordingly, Uncle Sam, who has provided part of the financing, is keeping some of the secrets about her. Her compartmentation—the number and location of watertight bulkheads with their automatic doors—is not being told.

Details of the power plant also are shielded by security. Certain things, however, are evident about the punch in the United States. Here is a ship of 51,500 gross tons, as against the 80,000 or so of the Queen Elizabeth and the Queen Mary. Yet this ship will carry almost as many passengers as the Queens and will carry them as fast. This means that important space has been gained somewhere, and it’s a good guess that it has been gained in boiler room, engine room and fuel storage.

The boilers and turbines operate at very high temperatures and high pressures. To handle these in the small space and weight called for new tricks by the metallurgists who worked out the alloys and by the fabricators who designed and built the machinery. In the laboratories and shops of the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co., which built the vessel, and of Westinghouse and Babcock & Wilcox, which built the engines and machinery, technicians took all that was known about marine propulsion and added a few new items.

Air Conditioning a Problem

The air conditioning was a highly desirable feature but its headaches were many. Finding space for the pumps, fans, ducts and controls was one of them. There are really 50 independent air-conditioning systems, and their ducts range in size from three inches to some that are big enough to drive a truck through. And once fitted in— on paper—there still remained the problems of building them and making them work.

The space problem was one for the designers. As fast as they cleared a blueprint it went to the sheet-metal shops at Newport News and the men began cutting out and assembling the fantastic shapes that had to carry the air around corners and up and down in the ship. Subassemblies were made as large as possible and stacked up on the dock. There they looked like the principal ingredient of alphabet soup—and in a foreign language at that. But they were fitted in place and hooked up.

Making the air-conditioning systems work was a special problem. Air conditioning at sea offers different problems than on land. There is more moisture in the air most of the time; there are greater contrasts of temperature inside and out. The problem of condensation was severe. It was solved by insulation and by using filter traps at intervals all along the ducts. These collect the moisture in a few spots rather than let it accumulate anywhere on the surface of the ducts. Another feature of the system is the thermostatic control in each cabin. All the air, filtered from the outside, is circulated in the ship at 50°. When it reaches a cabin it passes through an electric heating unit controlled by the thermostat; the passenger in an outside cabin may want more heat, one in an inside may want more cooling. Each will get what he wants.

Aluminum Was Tricky

The use of so much aluminum, in so many ways, called for new tricks. Plain sheet was no problem, and some shapes could be stamped, molded or extruded. But when it came to the stacks it was economic folly to think of shaping them with dies and presses. The heavy sheets could not be worked like steel, with rollers or torches and hand hammers, because aluminum just won’t shape that way. It had to be worked slowly and carefully by hands and clamps and special jigs. And when the stacks were done they were so big they had to be cut in half to be lifted into place.

The aluminum rails were turned out to approximate dimensions, including all the curves and fittings, in the shops of the Aluminum Co. of America. Then they were put in place, with precise machining, on the ship. Next they were marked, removed and shipped back to Alcoa for “alumilite” coating, the final finishing process. And then they were sent back to the ship for permanent installation.

Aluminum panels and decorations had to go through much the same laborious process. Aluminum rivets were handled like trick confectionery. Received from the factory, they were first heated to 1,040°, to “smooth out” the alloys, then quenched in water and rinsed in alcohol. To prevent the rapid aging which takes place at ordinary temperatures, the rivets were sunk in freezer cabinets at 40° below zero. Thereafter they were stored in insulated containers (including standard ice-cream cabinets) until they were driven. Once in place the aging, which results in greater strength, could take place.

The virtue of all this aluminum topside is of course its lightness. Averaging one third the weight of steel, it lowers the ship’s center of gravity, in turn reducing her tendency to roll.

Behind all these innovations is the genius and drive of a man generally considered the country’s No. 1 naval architect. He is William Francis Gibbs of the New York firm of Gibbs & Cox. Designer of the America, the country’s largest passenger ship now in service, and other major merchant craft as well as many types of naval vessels, he has for many years advocated such a supership as the United States—in the top class for speed, completely fireproofed, air-conditioned, luxurious. It took a lot of persuading, over the years. But his dream began to turn to reality on April 7, 1948, when the Government’s Maritime Commission and the United States Lines agreed on a financing plan and the Newport News yard was given the word to go ahead with the construction. The original contract price was a little under $70,000,000; modifications at the behest of the Government have raised that figure considerably.

For its money the nation has a lot of ship to show. In peacetime the United States will maintain its North Atlantic express run and few doubt that it will take a shot at the record now held by the Queen Mary —3 days 20 hours and 40 minutes, eastbound. All this means prestige and patronage. In wartime the ship, as the nation’s largest transport, could carry 14,000 to 16,000 troops as far as 10,000 miles without a stop. Peace or war, a lot of ship.

Read the original story in the_ Popular Science _archives, and see how the United States _looks today._