I swipe an alcohol-soaked gauze pad over my younger brother’s left thigh, an inch below the hem of his SpongeBob boxers. As I screw the needle into the injection pen, Alex feeds me instructions. It’s my first time, but already it’s his 37th.

“Here are the rules: Insert the needle quickly and gently, but only when I say so,” he says, taking the pen to pantomime the motion. He removes the first of two protective caps and turns a knob on the pen–one, two, three, four, five clicks–and watches intensely as his dose is released into the barrel.

“Make sure the skin dimples. That means the needle is all the way in,” he continues. “Press the button until it clicks, then hold it there for 5 seconds. Keep the skin dimpled, otherwise all the medicine won’t go in me. When you take out the needle, do it straight up and fast. And, Jenny, please don’t hit a vein. That huwts me.” Suddenly, dropping his r, Alex sounds much more like his 9-year-old self.

I pinch a clump of skin between my thumb and index finger and wait. “OK,” he whispers. But I can’t do it. “OK,” he repeats. I pierce the fatty tissue and wince–and take it as a compliment that he doesn’t. “Keep dimpling!” he yells.

Here’s the thing: My brother isn’t sick. He’s short. Shorter than every boy and girl in Ms. Lemcke’s fourth-grade class, shorter than 97 percent of boys his age. What I’ve just shot into his 3-foot-11-and-three-quarters-inch, 50-pound body is Humatrope, a lab-brewed human growth hormone (hGH) nearly identical to the hGH secreted by the pituitary gland, the critical metabolic hormone that regulates not only height, as its name suggests, but also cardiac function, fat metabolism and muscle growth.

Alex’s quest for “enheightenment,” as I’ve come to call it, began last summer just as the Food and Drug Administration expanded its approved uses of Humatrope, Eli Lilly & Co.’s recombinant hGH, to include children of idiopathic short stature (ISS)–kids who are extremely short for reasons that are not entirely understood. Kids who, like Alex, are teased or ignored by classmates who may trump

their height by a foot–but whose “condition” may be caused by nothing more than genetics. This groundbreaking and controversial FDA ruling made Humatrope available to 400,000 American children expected to grow no taller than 5 feet 3 in the case of boys and 4 feet 11 in the case of girls, putting them in the bottom 1.2 percentile. For Alex, the nightly hGH shots will probably continue for six to eight years–all to make this otherwise healthy boy grow taller.

Human growth is an invisible but intense process, an intricate and little understood web of genes, hormones and other variables. Genetics aside, growth hormone may be the single biggest player. Between 10 and 30 times a day, your hypothalamus sends a growth hormoneâ€releasing hormone to the garbanzo-bean-size pituitary gland at the base of your brain. Each time the pituitary gland receives a signal, it spits out a small amount of growth hormone. Although scientists think a small percentage of hGH travels to your bones, a majority of the hormone latches onto binding proteins, which carry it to receptors in your liver cells. This triggers the secretion of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), a protein that promotes bone growth in children and teenagers until their growth plates, areas at the ends of the bones, fuse, at around age 17 for boys or 15 for girls. After that, growth hormone continues to regulate the metabolic system, burning fat and building muscle, but we produce exponentially less hGH each decade after puberty. Thus, the teenager who can routinely “supersize it” without consequence ages into the 30-year-old whose beer and burgers go straight to his gut.

In 1971, Berkeley chemist Choh Hao Li synthesized the growth hormone molecule, an enormous biotech breakthrough, and in 1985 synthetic growth hormone was approved by the FDA to treat growth hormone deficiency. Prior to the drug’s development, medicinal growth hormone was scarce. What did exist had to be extracted from the pituitary glands of human corpses–most of the time legally, but occasionally by pathologists being paid by suppliers to remove the hormone without permission from the deceased’s family. As a result of the shortage, hGH treatment was conservative, reserved for kids who made very little if any growth hormone themselves. Between 1963 and 1985, 7,700 patients in the U.S. took the hormone. Ultimately, 26 of these patients died of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD); the fatal brain disease that’s similar to mad cow is thought to have contaminated a batch of the pituitary hormone doled out in the ’60s and ’70s. The FDA banned growth hormone when the first two cases of CJD were reported in early 1985–just in time for the agency’s approval, later that year, of the synthetic version.

Suddenly, the growth hormone supply was unlimited, safer and less expensive, opening the door for looser diagnoses, along with higher and more frequent doses. By 1988 what had once been a niche drug prescribed to treat dwarfism was shattering all market expectations, chalking up more than a half billion dollars in annual sales.

At the time, I was 11 years old, and a ripe candidate for growth hormone supplementation. I had been born in the fifth percentile for height, but at age 5 my “growth velocity” started slipping, and by 11, I was hovering below the first percentile. Blood tests revealed that I was only producing “borderline acceptable” levels of growth hormone. “Growth hormone injections may be an option,” Yale pediatric endocrinologist William Tamborlane told my parents. The prospect terrified me. “I don’t care if I’m a midget! It’s what’s inside that counts!” I protested. “I’m not having a shot every day.”

Further testing showed that my thyroid gland was malfunctioning, a definable and common condition called hypothyroidism. Tamborlane prescribed a pill (which I will take every day for the rest of my life), and my growth velocity picked up immediately. Still, I was told that I would never surmount the magical 5-foot threshold.

That’s because most short children can place primary blame for their stature on the genetic lottery. “Want to be taller, Jenny?” I remember Tamborlane asking me as his eyes shifted between my slumping growth chart, my X-rays and my mom and dad. I nodded eagerly. “Well, you should’ve picked different parents.” He chuckled, while I considered the merits of a parentectomy. Today I’m 26 years old and my height has topped off at . . . 5 feet 1, thank you very much.

Fifteen years after I flirted with growth hormone treatment, biotech’s baby has exploded into a $1.5 billion industry that has reached more than 200,000 children and sent many more to the doctor wondering if hGH is for them–including my brother Alex. When my mom called to tell me Alex was growth-hormone-deficient and would soon begin injections, I was skeptical. The prospect of having a shot every day had sent fear through my own little body, and now, as an overprotective big sister, I didn’t want my brother’s carefree childhood to be interrupted by such stress–and such a serious, understudied medical treatment–unless it was entirely necessary. Is being short so horrible that it should be medicalized and treated as an illness?

My thoughts were interrupted by my mom’s voice, bringing me back to reality. “Nurses are coming over next week to show us how to administer the injection,” she said. The decision had been made.

As the 6 train squeals under Manhattan’s Upper East Side, Alex’s Nikes sway three inches above the floor. My brother is a happy kid whose sprite profile doesn’t resemble that of the typical round-faced growth-hormone-deficient cherub. He’s silent now but only because his mouth is full of jellybeans. The train reaches our stop, and Alex places his sticky little hand in mine.

“Excuse me,” he says politely as we jostle our way off.

A surprised middle-aged mom looks up from her book. “My, you are much more polite than my kindergartener,” she says.

It’s been about two weeks since Alex began his nightly injections. Before that, he might have flinched at this well-intentioned under-estimate of his age. But today, he squares himself a bit and responds with a certain pride: “I’m 9 years old,” he says, “and I’m on Humatrope!”

It strikes me, not for the first time, just how important the drug has become to Alex. He yearns to be taller. As the youngest of six, he knows how to get noticed–our family joke is that he swallowed an amplifier–and what he lacks in stature he was dealt in personality. But at school, where tall kids hold the social scepter, his big personality is overlooked.

“Everyone says that it’s what’s inside that counts, and that makes me feel good,” Alex says, “but if I was the tallest instead of the shortest, everything would just be better. People would sit with me at lunch, I’d have more friends, and people in my class wouldn’t make fun of me and call me Little Everett. And I’d be a better soccer goalie. I think 6 feet would be good.”

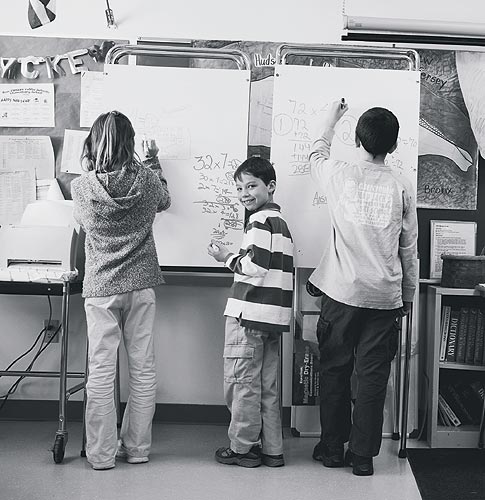

Studies show that half of short kids report being teased and three-quarters say they’re treated younger than their age–but keep in mind that this is an awkward age to begin with. Starting at about age 10, grade-wide height discrepancies tend to widen dramatically, which just adds fuel to the broader stew of middle school insecurities most of us shudder to recall. This is the age at which families often become conscious of and concerned about growth issues–because discrepancies are suddenly so visually apparent.

When I was in fifth grade, the boys would chase me down the hall on their knees playing “catch the midget,” and one of the tougher girls would taunt me: “You’re so small I need a microscope to see you.” But before feeling sorry for me, consider my classmate Kelly (Editor’s note: Name has been changed), who was 5 feet 10, a full 2 feet taller than I was–a virtual fifth-grade giant. (Given social norms, it’s appropriate to compare the experience of being a short boy to that of being a tall girl.) Kelly was tortured so badly throughout adolescence that at 18 she became bulimic. When her weight dropped to 115 pounds, she was hospitalized. “I thought it would make me smaller and more attractive,” she recalled in a recent phone conversation. “It almost killed me.”

Being a tall girl is so psychologically traumatic, in fact, that in the 1950s, doctors began giving tall girls estrogen as a growth suppressant. In high doses, the hormone stimulates cartilage maturation without causing an increase in height, which means the girls stop growing earlier. In Kelly’s case, treatment was discussed, but doctors were confident, based on her bone development, that she wouldn’t grow much taller than 6 feet. Good call: Today Kelly is only an inch taller than she was in fifth grade. And although no formal long-term studies have been done, tall girls treated with estrogen have reported increased incidences of miscarriage, endometriosis, infertility and ovarian cysts. Yet a survey taken last year reported that one-third of pediatric endocrinologists have offered the treatment at least once in the past five years.

Learning about the side effects of estrogen therapy only increased my apprehension about treating Alex with hGH. Armed with a small forest of research, I drove up to Yale†New Haven Children’s Hospital to unload my worries on Dr. Myron Genel, Alex’s pediatric endocrinologist.

With his white hair and white lab coat, Genel looks the prototypical old-school doctor, the kind you imagine making house calls with his little black medical kit. I take a sip of my coffee. “This won’t stunt my growth, will it?” I joke. “Too late to worry about that,” he replies.

I reach into my bag and pull out binders of research: diagrams of the growth process, historical time lines, and a folder labeled “risks,” which is packed with studies. “How concerned should my family be about the risks?” I ask.

I wait for reassurance–or, in any case, for a defense of Alex’s treatment. But Genel surprises me.

“We honestly don’t know the long-term side effects, and I think that’s a reason for real concern,” he says. “We’re using a hormone that promotes growth, and there are things whose growth we don’t want to promote. IGF-1, for example, has been shown to play a role in the development of malignancies in tissue culture.”

This I knew. Multiple studies of human serum specimens have shown that elevated levels of IGF-1 identify people at higher risk for developing breast, prostate and colon cancer, and tumor specimens, most studies show, have more IGF-1 receptors than normal adjacent cells. Although it’s not yet known whether an abundance of IGF-1 actually causes malignancies or is merely associated with some other risk factor, it is a reason for concern because growth hormone is what stimulates the liver and tissues to produce IGF-1.

But Genel explains that he’ll test Alex’s IGF levels every three months to make sure they’re in what’s considered the normal range. “In theory, if we keep his growth factors at an acceptable level, he’s not at risk,” he says.

I scan my list of questions, typed up in order of progressing intensity, and zoom to the bottom. “Given the risks, what makes Alex a good candidate?”

Again his response surprises me–this time because it challenges my assumption that Alex is in fact a good candidate for treatment. “We can define those youngsters who make virtually no growth hormone, because they have a very typical presentation,” he says. “And we can generally sort out those youngsters who make an ample amount of growth hormone.

We have a very difficult time, however, defining youngsters like your brother, who make some growth hormone, but who possibly don’t make enough.”

He explains that although Alex’s levels of IGF-1 are low and his height has gradually declined to the first percentile, he does produce some growth hormone.

“Your brother is a murky case, and there are enough questions about the safety and efficacy of this drug that I cannot say one way or another whether he should definitely receive treatment,” he continues. “Frankly, I felt we could wait–but not very much longer–and gather information. It was a decision that your family made and, I suspect, Alex made.”

Here is a manifestation of just how complicated and unpredictable the growth process is: It’s impossible to measure hGH levels using a simple blood test. Because the hormone oscillates in the blood, constantly peaking and sinking, a hundred samples can yield a hundred different answers. So doctors must rely on growth-hormone-stimulation tests, where the patient is injected with an artificial agent that stimulates the pituitary gland to produce growth hormone. After the agent is injected, nurses sample the patient’s blood every 30 minutes for 2 hours, hoping to catch the pituitary operating at full strength.

“These are artificial tests,” Genel says. “None of them tell us anything about what a youngster does under normal circumstances. It only tells us that if you give them an artificial stimulus, the pituitary gland will release hormone.”

Genel shows me my brother’s test results: Alex produced readings ranging from 0.11 to 9.9 ng/ml. Though most doctors look for a top level of at least 10 as an indicator of healthy hormone production, Yale has a lower benchmark of 7 or greater. So by Yale’s standards, Alex passed. My parents, I realize, have no idea that Alex may not be growth-hormone-deficient by some careful definition; they believe he is clinically deficient. Essentially, my little brother is an experiment.

Over dinner that night, my mother and father recall the day Alex’s test results arrived in the mail. Startled by the low numbers, they assumed he was producing far too little growth hormone. They had no idea growth hormone production is so difficult to measure. “I’m a parent, not a scientist,” my mom says. “I shouldn’t have to know that.” It’s safe to take him off the drug, I tell them: “It’s not too late to change your mind.”

But despite the day’s revelations, they decide to move forward with treatment. Alex’s confidence has already soared since starting Humatrope; they don’t have the heart to disappoint him. Besides, my parents say, they’re concerned Alex will have fewer professional opportunities, and worry he won’t find a woman to be with, if his height remains in the basement.

Such anxieties, of course, are hardly unique to my parents–and, in fact, a quick glance at the research would appear to back them up. A recent University of Florida study, for example, found that each extra inch of height amounted to $789 more a year in pay. So someone who is 6 feet would be expected, on average, to earn $5,523 more annually than someone who is 5 feet 5. Another study indicates that just 3 percent of Fortune 500 CEOs are shorter than 5 feet 7, and more than half are taller than 6 feet, though only 20 percent of the population is.

But it’s not as simple an equation as these numbers make it seem, says Dr. David Sandberg, an associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Buffalo. Sandberg’s studies have found that although short kids are teased and treated younger than their age, there is no evidence that making them 2.5 inches taller will make any difference in their quality of life. “Our lives are so much more complicated than one single factor,” Sandberg says.

In clinical trials by Humatrope manufacturer Eli Lilly, children taking the drug grew on average 1 to 1.5 inches more than the placebo group; 62 percent of the kids tested grew more than 2 inches over their predicted adult height, and 31 percent gained more than 4 inches. This would land Alex, whose predicted height without growth hormone is about 5 feet 6, somewhere between 5 feet 7 and 5 feet 10.

Dr. Harvey Guyda, chair of the department of pediatrics at McGill University in Canada, questions the studies, especially given what he describes as a high dropout rate. In the Eli Lilly studies, he points out, only 28 percent of the placebo and 42 percent of the growth-hormone- therapy subjects completed the study; it seems reasonable to assume, he says, that the subjects who endured the study were the ones who demonstrated the most extreme growth.

“The mantra is that healthy, short kids are handicapped, abnormal, have all sorts of problems, and we have to do something,” says Guyda, who testified against the FDA’s approval of Humatrope for treating kids with ISS. “But there is no data to prove that these kids are any different from normal-stature children, and there is absolutely zero data that says when you give growth hormone to a kid who’s said to have this psychosocial problem because he’s short there’s any benefit. Prove to me that a few extra inches is worth the cost of daily injections.”

Financially alone, that cost, according to Guyda, amounts to $10,000 per centimeter for a growth-hormone-deficient kid, and somewhere between $22,000 and $43,000 per centimeter for kids with idiopathic short stature. For now, my parents’ insurance company, Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield, has agreed to cover Alex’s treatment, but not every short child has insurance or a pediatric endocrinologist to recommend treatment. The not-surprising result is that any advantage hGH does confer will likely go to already advantaged patients: rich, white American males. (For every two girls who receive treatment, five boys do; this is at least partly explained by the fact that boys suffer more discrimination in relation to their short stature than girls do.)

A week before Alex’s three-month checkup, I return to Yale, this time to meet with Tamborlane, my own pediatric endocrinologist, whom I haven’t seen since my last appointment eight years ago. I’m especially interested in his opinion about Alex because Tamborlane, now the chief of pediatric endocrinology at Yale, voted for the approval of Humatrope to treat idiopathic short stature. We meet in the cafeteria, and although I’m not looking for a free checkup, he palpates my throat right there. “Thyroid feels healthy,” he reports.

Tamborlane voted for the approval, he tells me, because the drug was already OK’d to treat some groups of children who produce plenty of growth hormone–children with Turner syndrome, a genetic abnormality; children born small for gestational age; and children with chronic renal insufficiency, a kidney disease. In each of these cases, hGH isn’t treating the disease, it’s treating the resulting undesirable physical characteristic–short stature. In kids with ISS, though, it’s even more ambiguous because the disease, if there is one, is unknown.

I present Alex’s case to Tamborlane, explaining my family’s motivations and the uncertainty surrounding the diagnosis. I tell him that although I want Alex to have every advantage and the best possible quality of life, I’m concerned about the drug’s unclear benefits and the potential long-term risks for kids who are short for reasons that aren’t fully understood.

“If Alex were your son,” I ask, “would you put him on hGH?”

Tamborlane leans back and pauses to consider the question.

“Given the uncertainties, probably not. I was a short, geeky kid at a football prep school, and I survived–maybe even gained something from it,” he says. (He’s now 5 feet 9.) “All signs say Alex would probably grow to a very livable height without the growth hormone.”

In early November, we bring Alex to Yale for his first checkup. By now, the injection has become routine–slotted into a 9 p.m. Nickelodeon commercial break–and my family is already noticing changes in Alex’s body. His muscle tone is visibly improved, and his pants are suddenly too short. In the waiting room, I jot down a few things to mention to the doctor: Alex’s appetite is uncharacteristically voracious; his growth pains are intensifying; and his hair is dry and brittle.

The room used for measuring height and weight is wallpapered with drawings by patients with a variety of metabolic disorders. One depicts a small, sad-looking stick figure labeled “before” and a taller, much happier stick figure labeled “after.” Alex stands to the left of this, back to the wall, grinning in anticipation of his “after.” The nurse scribbles on his chart and ushers us into the examining room. Alex is anxious because while we swear he’s grown at least 3 inches, we’re not positive because we haven’t measured him yet–psychologists recommend we don’t measure Alex at home.

“124.8 cm,” Genel announces finally. “That’s just about 4 feet 1, about an inch and a half in three months.”

“Wow,” says my mom, extrapolating 6 inches of growth a year.

“That’s all?” says Alex. “All those shots for one measly inch?!”

Genel warns them not to take the results too literally. “These are positive results,” he says to Alex. Then, turning to my mom: “But it’s too early to attribute this response to the treatment.”

Indeed, there’s no telling what the results of Alex’s treatment will be; even at $20,000 a year there are no guarantees. Some kids end up in the 60th percentile, while others never crawl above the fifth. I’m still left wondering why we’re rolling the dice on a healthy kid, particularly when the benefits of a few extra inches are unproven and the risks are unknown. At the same time, I’m rooting for results–and we leave the doctor’s office cautiously optimistic that the treatment is having an impact. We’re further reassured three months later, in early February, when Alex’s next official measurement comes in: He’s 4 feet 2 and a quarter inches, a full 2.5 inches taller than he was six months earlier when he began treatment.