There’s been growing speculation in recent years that the community of bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms dwelling in the gut somehow contributes to autism. However, scientists reported this week, the reality may in fact be the reverse.

“Instead it looks like characteristics of autism contribute to microbiome differences, almost turning the hype or the proposed mechanism on its head,” says Chloe Yap, an MD/PhD candidate in psychiatric genomics at the the University of Queensland and the Mater Research Institute in South Brisbane, Australia.

Children diagnosed with autism are more likely than their peers to experience gastrointestinal complaints such as constipation, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. This has led some researchers to propose that the gut microbiome might differ in autistic people and perhaps even cause the condition.

There are studies indicating that a number of conditions, ranging from inflammatory bowel disease to rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and depression, are in some way influenced by the gut microbiome. However, the evidence for the microbiome causing autism, or even being different in autistic people, is pretty weak, Yap says.

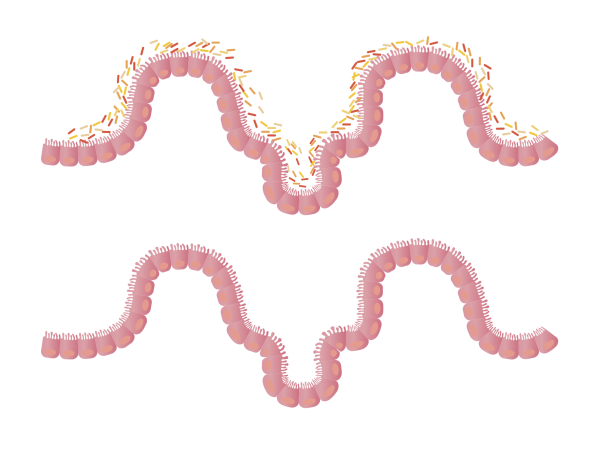

She and her colleagues examined stool samples from nearly 250 kids, and found no link between a diagnosis of autism and the composition of the microbiome. However, children with less varied diets were more likely to have less diverse microbiomes, as well as restricted or repetitive interests and sensory sensitivities, the team wrote on November 11 in the journal Cell.

“Children on the autism spectrum often prefer to eat a narrow selection of foods, and then that affects the microbiome,” Yap says. “So in other words, it’s a case of mind over microbes rather than the other way around.”

[Related: Millennium-old poop reveals the surprising diversity of our ancestors’ microbiomes]

Despite the lack of evidence supporting the gut microbiome’s contribution to autism , she says, “There’s sort of been this building momentum and hype around the autism microbiome, which has led to some so-called therapies that claim to help or support children on the spectrum by modifying the microbiome.” These include probiotics, fad diets, and fecal microbiota transplants.

To investigate whether there was any basis for these claims, Yap and her team took stool samples from 247 children and adolescents between the ages of 2 and 17 and analyzed them for microbial DNA. The participants lived across Australia and included 99 kids who’d been diagnosed with autism, 51 of their siblings who hadn’t received a diagnosis of autism, and 97 unrelated children who also hadn’t been diagnosed with autism. The team also collected health, lifestyle, dietary, and genetic information from the children.

The researchers found no significant differences in the overall composition of the microbiomes of children with and without autism diagnoses. The team also didn’t find any connection between the microbiome and sleep problems (which are common in autistic people).

Additionally, the team searched for 607 bacteria species and identified just one that was noticeably less abundant in stool samples from kids on the autism spectrum.

They did, however, observe that children with more watery stools (a common sign of gastrointestinal issues) had microbiomes that were more limited in diversity. Children who ate fewer different kinds of foods also had less diverse microbiomes.

Although there wasn’t a direct link between a diagnosis of autism and the microbiome, children on the autism spectrum tend to have less diverse or poorer-quality diets according to an assessment known as the Australian Recommended Food Score.

To find out which characteristics might be driving this relationship, the researchers analyzed data on the children’s behavior and genetic differences associated with common autistic traits. “We found that measures of restricted interests and sensory sensitivity, both of which are core diagnostic domains of autism, were associated with [having a] restricted diet,” Yap says. Having a less varied diet would in turn lead to a less diverse microbiome and gastrointestinal problems, she says.

The findings suggest that “treatments” for autism that target the microbiome aren’t based on solid evidence. However, Yap says, the findings do highlight the importance of helping kids on the autism spectrum have healthy, balanced diets. “Having a good diet is really important for long-term wellbeing and development, so that’s something to really start looking into,” she says.

Still, the researchers say, it will be important to verify the findings by examining larger groups of participants from around the world. “We’re aiming to progress this as a team, but hope that others in the field do similar analyses,” Jacob Gratten, the leader of the Mater Research Institute’s Cognitive Health Genomics group and another coauthor of the findings, told Popular Science in an email. The team also plans to follow children over time to see if variations in the gut microbiome in infancy are related to later autism diagnosis.