This article was originally featured on Undark.

Back in the year 2000, sitting in his small home office in California’s Mill Valley, surrounded by stacks of spreadsheets, Jay Rosner hit one of those dizzying moments of dismay. An attorney and the executive director of The Princeton Review Foundation, the philanthropic arm of the private test-preparation and tutoring company, The Princeton Review, Rosner was scheduled to give testimony in a highly charged affirmative action lawsuit against the University of Michigan. He knew the case, Grutter v. Bollinger, was eventually headed to the U.S. Supreme Court, but as he reviewed the paperwork, he discovered a daunting gap in his argument.

Rosner had been asked to explore potential racial and cultural biases baked into standardized testing. He believed such biases, which critics had been surfacing for years prior, were real, but in that moment, he felt himself coming up short. “I suddenly realized that I would be deposed on this issue,” he recalled, “and I had no data to support my hypothesis, only deductive reasoning.”

The punch of that realization still resonates. Rosner is the kind of guy who really likes data to stand behind his points, and he recalls an anxiety-infused hunt for some solid facts. Rosner was testifying about an entrance exam for law school, the LSAT, for which he could find no particulars. But he knew that a colleague had data on how students of different racial backgrounds answered specific questions on another powerful standardized test, the SAT, long used to help decide undergraduate admission to colleges — given in New York state. He decided he could use that information to make a case by analogy. The two scholars agreed to crunch some numbers.

Based on past history of test results, he knew that White students would overall have higher scores than Black students. Still, Rosner expected Black students to perform better on some questions. To his shock, he found no trace of such balance. The results were “incredibly uniform,” he said, skewing almost entirely in favor of White students. “Every single question except one in the New York state data on four SATs favored Whites over Blacks,” Rosner recalled.

There was something going on here, he thought: not with the students, but with the test.

Troubled and curious, Rosner then acquired SAT test data not just for New York, but for the entire United States, from two tests — one conducted in 1998 and another in 2000. The new data sets had information that could help him decipher how questions were chosen for use in the tests.

In making that inquiry, Rosner knew that all of the questions that contributed to a student’s final score had passed the SAT’s “pre-testing process,” meaning they had appeared in experimental sections of previous exams where they did not count. (Pre-testing questions are routinely inserted into SATs and students do not know which questions are being pre-tested.) Instead, they serve as trial runs — new questions that the makers of the SAT are considering adding to the official test in future updates, depending on data gathered from real-world exams. Using racial and gender data gathered from those real-world exams, Rosner then sought to infer whether there was an internal preference for pre-tested questions on which one racial group outperformed another.

Of 276 math and verbal questions that passed pre-testing and ended up in the official tests, Rosner found that White students outperformed Black students on every one. That outcome struck him as statistically impossible — unless the pre-test questions that White students excelled at were disproportionately making it into the final tests. While he had only limited data on pre-test questions themselves, it seemed obvious to Rosner that a selection bias was at work, with pre-test questions that Black students excelled at — which he called “Black questions” — being left on the cutting room floor. “It appears that none ever make it onto a scored section of the SAT,” Rosner wrote in a 2012 book chapter on the topic. “Black students may encounter Black questions, but only on unscored sections of the SAT.”

The reason, Rosner suggests, isn’t to intentionally give one group an advantage — though that’s the outcome just the same. “Each individual SAT question ETS chooses is required to parallel the outcomes of the test overall,” he continued in the book. “So, if high-scoring test-takers — who are more likely to be White (and male, and wealthy) — tend to answer the question correctly in pre-testing, it’s a worthy SAT question; if not, it’s thrown out. Race and ethnicity are not considered explicitly, but racially disparate scores drive question selection, which in turn reproduces racially disparate test results in an internally reinforcing cycle.”

Even today, Rosner describes his reaction to the disparity in a single word: “stunned.”

Absent an ability to shore up early education and eliminate exam-question bias, the score gap simply gives racial essentialists a justification for their own prejudices.

Since their advent in the early 20th century, standardized tests have come to possess an astonishing amount of power in American society — helping to dictate who succeeds and moves upward through the educational and, very often, economic ranks, and who does not. But ample evidence, including Rosner’s, suggests that the tests have always fallen short of being the objective sorting tool they purport to be.

No one, after all, denies that standardized test score results have long varied by racial and ethnic category. What remains hotly disputed is why. Some stakeholders see the performance gap, alongside data like that collected by Rosner, as clear evidence that the tests themselves are biased — a conviction buttressed by standardized testing’s early roots in white supremacy and their later use to reinforce school segregation. They have been used not only to shape the country’s economic and racial hierarchies, critics say, but to reinforce disproven beliefs about the nature of intelligence, and stereotypes about who’s smart enough to succeed and who’s not.

Others argue that it’s not the tests that are biased — at least not the modern versions — but the foundations laid by elementary and high school systems endowed with wildly different resources, often skewing along both economic and racial lines.

Still others argue that both explanations can be true, and that the real problem with a test-obsessed society is that, absent an ability to shore up early education and eliminate exam-question bias, the score gap simply gives racial essentialists a justification for their own prejudices: If Black and Brown students underperform compared to Whites, they declare, it must be genetic. Denying racists a talking point may not be the primary motivator for reforming both education and testing, but reform, most good-faith stakeholders argue, is sorely needed.

Rosner did deliver his data-based testimony on standardized testing in the Grutter vs. Bollinger case. The lawsuit was brought by a White University of Michigan Law School applicant who argued that the university’s affirmative action policies effectively discriminated against her when she was denied admission despite, among other things, her strong test scores. Rosner’s contribution was in support of the university and in 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision, would reject the student’s argument, keeping affirmative action policies in place.

Even so, the College Board, the 122-year-old nonprofit association of educational organizations that develops and administers the SAT, the Advanced Placement exams, and the College-Level Examination Program, among others, says it disagrees with the way Rosner did that initial analysis. And if there is a measure of bias to its tests at all, the organization argues that it is mostly a product of disparate and unequal access to educational resources in the U.S. — and perhaps a level of cultural bias that slips through. When asked about Rosner’s findings, the College Board, in an email sent to Undark by communications director Sara Sympson, noted: “Real inequities exist in American education, and they are reflected in every measure of academic achievement, including the SAT.”

Awareness of that point, the email continued, means that the SAT has been continually evaluated and redesigned toward a more culture-neutral form of assessment.

Still, Rosner remains driven by that initial data-based evidence of injustice. He is currently involved in work to reduce the negative impact of law and medical school admissions tests. And, in the way that everything comes round, the affirmative action case that so influenced his path, Grutter v. Bollinger, is now part of a major reassessment of affirmative action being taken up by today’s U.S. Supreme Court, following lawsuits against both Harvard University and the University of North Carolina. Rosner, who has been working with the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law to support Harvard’s defense of affirmative action, is once again trying to make sure that the country’s top justices can see how the system skews. He emphasizes that he’s not accusing test developers and administrators of evil intentions. In fact, “I go out of my way to say that they are not racist,” he said.

But as the tests continue to exert real power, he’d like their bottom line to be acknowledged. And that bottom line, Rosner says, is a question: Do standardized tests support the status quo and white supremacy? The answer to that question, according to Rosner: “Obviously.”

While much of the conversation focuses on college-level gatekeeper tests like the SAT and ACT, the Graduate Record Examination, or GRE, and other graduate school tests such as the LSAT or Medical College Admission Test (MCAT), most U.S. students take an astonishing array of standardized tests meant to evaluate their progress much earlier, often beginning in elementary school. The use of such tests exploded after former President George W. Bush signed the No Child Left Behind Act into law in 2002, which required assessment-based school accountability.

By some estimates, the average U.S. student will have taken more than 100 standardized tests before leaving the K-12 system.

Whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing — and what role racial bias continues to play in the American testing regime — is a question that stirs passionate response. “I see them as tools that have been used to maintain White privilege and to maintain Black, Brown, and Indigenous deprivation,” said Ibram X. Kendi, the director of the Center for Antiracist Research at Boston University and the recipient of a MacArthur genius grant for his work in social justice. Kendi has publicly called standardized tests “the most effective racist weapon ever devised.”

Columbia University linguist John McWhorter, author of the 2021 book “Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America,” doesn’t hesitate to push back on these ideas. “No — the people who say that just don’t like or do well on tests themselves,” he suggested in a recent email exchange. McWhorter, who, like Kendi, is Black, sees anti-test attitudes as a way of dismissing Black competence. “If the tests are a way of keeping Black people down, then that means that Black people are inherently too dumb to perform on tests,” he said.

He agrees that some of the longstanding differences in test scores are cultural, and that this won’t likely change until the culture itself changes. But, McWhorter added, “we can’t go there until we stop excusing Black kids from serious competition via testing.”

The views of Kendi and McWhorter are bookends to a library’s worth of opinions on the matter. Some see the value in standardized tests; others see none. Some see real worth to assessing skills and knowledge, whereas others worry that the testing focus is so narrow that it doesn’t provide meaningful information. Some critics see a crooked system, stacked in favor of cultural power brokers, while others suggest that even if flawed, the testing enterprise offers essential information.

Everyone has something to say, and it rarely involves a shrug of indifference.

More than half of U.S. states adopted exit tests, which you had to pass to graduate from high school, from the 1990s to the 2000s, said Julian Vasquez Heilig, dean of the College of Education at the University of Kentucky. “At one point, Texas had 15 exit tests. And these had a dramatic effect on students of color,” he noted. “Even if they got straight As in school, they couldn’t graduate if they didn’t pass the test. This was completely crazy.”

Denise Forte, chief executive officer of The Education Trust, a national nonprofit which advocates for student achievement, countered this notion with something of a Rosner-like demand for evidence. Forte, who worked as a Congressional staffer when the No Child Left Behind Act passed, pointed out that the law’s demand for repeated student testing has helped provide a much better picture of the state of American education. As an example, tests have offered a detailed portrait of the educational impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, showing that U.S. students lost real ground in their math and language skills while schools were shuttered in response to spreading infections. A study released in October 2022 further showed this was particularly acute for those in high poverty, minority schools where online resources are in short supply.

Such national-level insights into the impact of policies, Forte argued, are obtainable through testing — and particularly testing that is uniformly administered to all students. “Back in the 1990s, before the NCLB required that every student be tested, there were schools that would send [some] kids out on field trips when state tests were given,” Forte recalled. “It would be ’You have a disability, you speak Spanish? Why don’t we take you out to the movies?” And she added, “Now they have to test everyone. And now we have a much richer data environment, one that can tell us more about what students need and what schools need.”

Such data, Forte pointed out, can be used to help develop better class lessons, improve teacher training, and bolster struggling schools.

Or rather it should be doing that. The problem, she said, is not the tests but our failure to respond to what they tell us in equitable ways. “In some places, the findings lead to system improvement,” she said. “In other places, they are used to knock schools, teachers, administrators, which is patently unfair.” We should, she added, try to strengthen the tests so they give us even better information about schools — and then actually use them to boost rather than punish. Because if we don’t use test data to improve education for all students, Forte wonders, then what exactly is the goal?

The U.S. is, of course, far from the only country to use standardized testing as a tool that shapes student success. In the U.K., students must take at least a dozen tests before they graduate from high school, including A-levels that determine whether they are considered college track material. (Interestingly, the lowest performers in the U.K. are White working-class boys, while ethnic minorities tend to do better on average, and have been steadily improving.) In Japan, students must pass a daunting entrance test to get into high school as well as college. And China requires an intensive college entrance exam that lasts more than nine hours.

But what arguably distinguishes the U.S. process is the aura of controversy and mistrust that has surrounded standardized testing since it first rose to prominence in the early 1900s — and later as part of a white-supremacist agenda designed to keep schools segregated even after the landmark Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which ordered the end of racially separate schools in 1954.

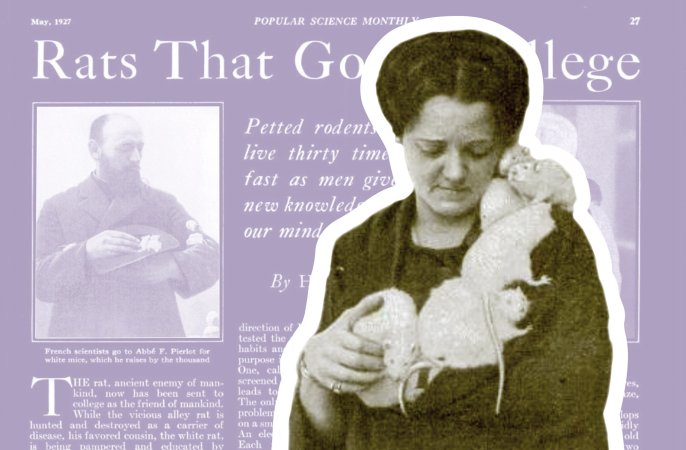

Interest in expansive testing began as the relatively young field of psychology gained increasing traction in the 1910s and 20s, Kendi says. It was a fledgling discipline, seeking to gain a reputation within the scientific community. “At the time, psychologists imagined that the way you gain legitimacy was saying that empiricism was at the heart of the work and that the work was of social use,” Kendi said. “So, these standardized tests are tools we have created, and they are used for social good, so we are relevant, and they are empirical, so we are scientific.”

“It’s hard to know if all of them actually believed in the hierarchy,” Kendi added. “But what I do know is that the standardized tests arrived right on time, in every period, with new theories and measures to justify racial hierarchy.”

At the time, the popular term for the assessments was “intelligence tests.” That description was pushed by Stanford University psychologist Lewis Terman, who developed the Stanford-Binet IQ test and coined the term “intelligence quotient.” Terman freely admitted that he developed his intelligence scale by testing mostly White, middle-class American students. It wasn’t worth his while testing immigrants, Terman explained, because “these boys are ineducable beyond the merest rudiments of training.” And he didn’t bother with Black, Native American, and Latino children either, as “their dullness appears to be racial.”

The first widely used standardized tests in the U.S. were the Alpha and Beta tests, developed by a colleague of Terman, Yale University psychologist Robert Yerkes. He proposed them as a way to help the Army commanders assess the intelligence of their soldiers. Yerkes designed two versions of the test: Alpha for soldiers who could speak and write English, and Beta — a test series using images — for immigrants who did not know English well, or Americans who had not been educated well enough to achieve literacy.

Yerkes declared that in either case, the tests measured innate intelligence rather than education. “It behooves us to consider their reliability and their meaning, for no one of us as a citizen can afford to ignore the menace of race deterioration,” he wrote.

What I do know is that the standardized tests arrived right on time, in every period, with new theories and measures to justify racial hierarchy.

Ibram X. Kendi

Even contemporaries of Yerkes and his collaborators argued that their assumptions and methodologies were hopelessly biased. The very need for two tests spoke to issues of education and language knowledge, they noted, and the questions themselves reeked of money and even the geographical privilege of the test taker. Among the multiple-choice questions on the tests:

• Cornell University is at Ithaca | Cambridge | Annapolis | New Haven

• The tendon of Achilles is in the heel | head | shoulder | abdomen

• Alfred Noyes is famous as a painter | poet | musician | sculptor

• The most prominent industry of Gloucester is fishing | packing | brewing | automobiles

To claim that such questions measured intelligence was pure nonsense, snapped journalist Walter Lippmann. “That claim has no more scientific foundation than a hundred other fads,” comparing it in substance to hyperbolic claims made for vitamins and other health supplements. In a letter to Terman, Lippmann further laid out his objectives in precise detail: “I hate the abuse of the scientific method that it involves. I hate the sense of superiority which it creates and the sense of inferiority which it imposes.”

Nevertheless, Princeton University psychologist Carl Brigham, a Yerkes collaborator, gathered the Alpha-Beta test results into an influential argument for white superiority in his 1923 book, “A Study of American Intelligence” — though he had to wrestle with some stubborn data to make his case. For instance, on the Alpha tests, Northern Black soldiers frequently outscored their Southern White rural counterparts.

Brigham acknowledged that Northern Black people often had better educational opportunities than Southerners, White or Black, but he theorized that some of the difference was because Blacks living in the North had a “greater amount of admixture of White blood.” Overall, he added, the tests underscored “the marked intellectual inferiority of the negro,” and Brigham suggested that too much of an admixture of Black and White blood would send America’s aggregate intelligence spiraling downward.

Brigham would later disavow these eugenicist positions, but his contribution to the conviction — tightly held in certain quarters of the American intellectual firmament at the time — that intelligence could be measured, and that White people were at the top of the measurement heap, was unmistakable. And just three years after the publication of his racist treatise, Brigham would oversee the adaptation of the Army tests into a new college entrance exam, first administered in 1926.

It was called the Scholastic Aptitude Test.

The eugenics-based origins to standardized testing are inescapable — and they are precisely why scholars like Kendi see them, even today, as a tool of white domination in the U.S. Other scholars, while also critical of the modern testing model, place less emphasis on test origins, saying that while their history is inarguably steeped in racism, modern testing has evolved beyond the facile arguments and racist motivations of scientists like Brigham and Yerkes.

“I don’t think of the test’s racist origins as still being a problem, although that stain is still there,” said Rachelle Brunn-Bevel, a professor of sociology at Fairfield University in Connecticut, who has done some notable analyses of test score gaps. Brunn-Bevel’s work has not made her a fan of standardized tests, but she also doubts that the modern SAT is tied to the motivated reasoning of racists. “There’s no question that with the creation of the SAT, it was designed to keep in place White Anglo-Saxon students, particularly males,” she said. “Right now, is that the focus? I don’t think so.”

The College Board, for its part, also firmly disavows those race-biased origins. Eugenics “is widely condemned today, and we condemn it totally. The SAT has been completely overhauled in the century since Brigham’s involvement and there is no vestige of his influence in the achievement-based test of today.”

Still, Brigham’s influence is not the only piece of complicated history still haunting the history of standardized testing. The 1954 decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown vs. The Board of Education of Topeka, which famously struck down racial segregation in schools, shook some regions of the country to their core — and no more so than in the American South. When Black students in Little Rock, Arkansas, for example, decided to attend a “White school,”

President Dwight D. Eisenhower had to send out the Arkansas National Guard to protect them. Southern legislators established a resistance and refusal network of support for each other, passing state laws that attempted to make the Brown decision illegal. “If we can organize the Southern states for massive resistance to this order,” declared then-U.S. Sen. Harry Flood Byrd, a Virginia Democrat, “I think that, in time, the rest of the country will realize that racial integration is not going to be accepted in the South.”

At the time, American colleges and universities hadn’t fully signed on to the idea of standardized admissions exams. They tended to be used mainly by the country’s tony private schools, and as Nicholas Lemann notes in his classic book on the subject, “The Big Test: The Secret History of the American Meritocracy,” they ably reinforced “a tradition of using tests and education to select a small governing elite.” In the South, that meant schools like Agnes Scott, Duke, and Emory. But now, the public universities were taking note. Two years before the Brown decision, the South Carolina College Organization hastily endorsed the use of admissions tests as “a valuable safeguard should the Supreme Court fail to uphold segregation in the state’s schools.” In June 1954, South Carolina became the first state to require standardized tests as a requirement for acceptance to a public university.

Others rapidly followed in Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Texas. In response to an inquiry by a University of North Carolina sociologist, Guy B. Johnson, university officials told him that standardized tests worked well as a legal way to enforce segregation because “the majority of Negro students are handicapped by an inferior educational background, as well as by other social and economic factors, and are not ready to compete with White students on equal terms.”

As Wake Forest University education professor R. Scott Baker details in his book, “Paradoxes of Desegregation,” Southern university administrators reached out to the Educational Testing Service, which today develops the SAT for the College Board (as well as administering the GRE and teacher tests, like Praxis) and received an enthusiastic response from an industry anxious to expand its reach. Part of the Southern idea, Baker said in an interview, was that standardized tests could be used to keep Black teachers from teaching White students.

Communications from ETS during this period, collected by Baker, show an organization with real faith in its tests and eager to expand its reach. And statements by Southern educators suggest that they weren’t hesitant about making clear their pro-segregation goals. “A few Negroes” would not be a problem, noted David Robinson, a lawyer in South Carolina at the time, but too many would lead to unwanted “mixing” on a large scale. Fortunately, he continued, the tests could be used to “legitimately disqualify” most Black applicants.

“They aren’t worried about what people will think,” Baker said. “They know their world.”

Still, as society moved forward toward today, the language became more circumspect. “That’s one of my key interests,” Baker added. “What kind of new language is being used [to talk about testing]? Folks are not going to now say ‘Gosh, we’re going to use these tests to discriminate.’” Instead, they may use a term like accountability to advocate for test usage.

There’s nothing wrong with the idea of accountability, Baker emphasized, if you trust the source — and “as long you have considered the intent.”

In a 1969 high-profile article in the Harvard Educational Review, University of California, Berkeley psychology professor Arthur Jensen posited that test score gaps between Whites and Blacks were indeed indicators of a lower Black intelligence that could never be overcome by education alone. “[T]here are intelligence genes,” Jensen informed The New York Times that year, “which are found in populations in different proportions, somewhat like the distribution of blood types. The number of intelligence genes seems to be lower, overall, in the Black population than in the White.”

Jensen’s work inspired a cadre of scientific followers. Harvard University psychologist Richard Herrnstein expanded on Jensen’s studies, for example, and in 1973 published the book “IQ in the Meritocracy,” which also argued that because intelligence was genetic, and differed by race, those unlucky to be in the wrong racial group could never brought up to par.

In 1994, Herrnstein, along with political scientist Charles Murray, a fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, published “The Bell Curve,” which amplified these arguments further. Leaning heavily on the work of scientists funded by the Pioneer Fund, a nonprofit established in the eugenics era and still well-known known for its promotion of white superiority, the highly publicized book went so far as to suggest that standardized tests can measure a person’s cognitive abilities — described as general intelligence or the “G” factor — and that the sum of these tests could be used to prove that Blacks are genetically inferior to Whites.

These ideas tend to flourish on the air of legitimacy that testing provides, however falsely, suggests Jack Schneider, an associate professor of education at University of Massachusetts Lowell and author of the 2017 book, “Beyond Test Scores.” “The arguments in ‘The Bell Curve’ are still around,” he said — adding with great unhappiness: “And they are still being repackaged as science.”

We’re living in a country with a deeply problematic racial history. So sometimes, we use the language of race, when what we’re really talking about is income or social class.

Jack Schneider

Among the many problems with “The Bell Curve” and similar treatises on race and intelligence is that the test-makers make no claims about intelligence and G-factors at all — precisely the opposite, according to the Educational Testing Service. “ETS’s position has always been that the standardized test scores its assessments produce offer one piece of data that contributes to the larger picture of who a learner is, what they know, and what they can do,” said Ida Lawrence, ETS senior vice president for research and development. She also emphasized that the score is basically a “snapshot of one single moment in time” of a student’s educational passage. ETS maintains that the score “should be holistically alongside other criteria.”

“Holistic” is a word the College Board emphasizes as well. “We’ve long held that SAT scores should be only one part of a holistic college admissions process. Scores should only be considered in terms of where students live and go to school and an SAT score should never be a veto on a student’s plans or ambitions.”

What standardized tests do an excellent job of measuring, many experts say, is a student’s economic class, as well as the resources available to them, the resources invested in their schools, and even the time and money they’ve been able to put into preparing for the tests.

Schneider put it this way: “For the most part, we have ignored class in the discussion about standardized testing. We’re living in a country with a deeply problematic racial history. So sometimes we use the language of race, when what we’re really talking about is income or social class. It’s absolutely true that test questions can and do undervalue cultural knowledge of Black or Latino families, when we’re looking at performance on standardized tests,” Schneider continued. “But let’s not forget that tests may undervalue something else. Does a person have access to … resources outside of school and will that young person arrive ready to thrive?”

A legal brief submitted in July to support Harvard University’s defense of its affirmative action program — currently under review by the U.S. Supreme Court — provides a slew of statistics, based on federal analysis of schools, that illustrate Schneider’s point. The brief from the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Education Fund notes that schools with a high number of minority students (Black, Latino, Indigenous) are less likely to offer advanced courses and that they have a higher percentage of inexperienced teachers and teachers who lack state accreditation. The brief also notes that such minority students are three to six times more likely than White students to attend high-poverty K-12 schools, which often are forced to hire teachers without expertise in the subjects they teach. In better funded schools, research shows, teachers are less likely to call on minority students in class or recommend them for college prep activities.

The NAACP brief also raises issues first surfaced by former ETS senior research psychologist Roy Freedle. He found that in SAT testing of vocabulary, Black students tended to score better on words that arise more frequently in an academic setting, while White students did better on more informal vocabulary words that reflected a comparatively affluent culture. The most famous example of this, perhaps, is the following multiple-choice analogy question, which appeared on some versions of the SAT dating as far back as the 1980s:

Runner: Marathon

A. Envoy: Embassy

B. Martyr: Massacre

C. Oarsman: Regatta

D. Horse: Stable

The answer — which would clearly favor students familiar with rowing — was C, and two education researchers, Mark Wilson of UC-Berkeley and María Verónica Santelices of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, would later confirm Freedle’s findings on the vocabulary bias issue. In their 2010 report, they wrote simply: “SAT items do function differently for the African-American and White subgroups in the verbal test.”

The SATs ceased to include these sorts of analogy-based questions altogether in 2005, but Wilson says in an interview that his own analysis and the work of others “did make me question the SAT in general. There are some serious questions about how the SAT is designed,” he added. “I became somewhat more cynical about it after seeing the pattern.”

Such doubts are spilling over. A recent Pew Research Center survey found that more than 60 percent of Americans believe that grade point averages should be a major consideration in college admissions. Only 39 percent believe the same of standardized tests. Following those sentiments, and perhaps spurred by the disruptions of the global Covid-19 pandemic, almost two-thirds of the country’s four-year institutions — from Harvard to the University of California system — have made SAT and ACT scores optional in admission applications.

One outlier in this trend is the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which made the tests optional during the first two years of the pandemic but reinstated its requirement for admissions tests in March 2022. (Disclosure: Undark is published by the independently endowed Knight Science Journalism Fellowship Program, which is based administratively at MIT.)

The university’s analysis had showed that it was better able to predict academic success for students if SAT or ACT scores — particularly the math sections — were part of the admissions process. “Our research can’t explain why these tests are so predictive of academic preparedness for MIT,” the institute’s dean of admissions, Stu Schmill, admitted in a blog post. “But we believe it is likely related to the centrality of mathematics — and mathematics examinations — in our education.” He emphasized that the decision was mostly based on this factor and that MIT does “not prefer people with perfect scores.” The university just wants to use all possible measures to assure success, Schmill wrote.

Wilson doesn’t dispute that the tests may offer some useful data. “I fear that not very reliable measures are used in its place,” he said. “And I worry that without something like a test, something we can call on for more data, we can’t get around the problem that schools give different sorts of grades.” If, as the NAACP brief notes, schools with more White students offer more advanced placement classes, then by nature of those classes, GPAs will be higher than in schools that offer none.

McWhorter, the Columbia University linguist, meanwhile, calls MIT’s move the right decision. McWhorter doesn’t deny that culture differences play a role in test score gaps. But he believes that “as the culture changes, so will the lag.” We’re too impatient for change, McWhorter suggested, and if you consider the long stretch of history, “the 1960s were 10 minutes ago.” Further, he has also come to believe that the tests do catch a kind of abstract intelligence, separate from the reasoning used in navigating day to day life — perhaps including the kind of math test performance tracked by MIT.

It’s insulting, he argued, to imply that Black students aren’t capable of that; rather than suggesting they are disadvantaged by life, McWhorter said, we should instead try to challenge them to show how smart they are.

Whether or not that’s fair, McWhorter’s take on testing is not shared by many of his contemporaries, who often feel that the era of uncritical acceptance of standardized testing has run its course, and that whatever insights are gained from such exams are too opaque and suspect to be of much use — particularly in a culture still struggling to overcome racial animus and economic inequality. “How can the enterprise of testing help us get toward the goal of equity we’ve been talking about?” asked Richard Welsh, an associate professor of education and public policy at Vanderbilt University.

If tests can’t move things forward, he added, then it’s entirely reasonable to consider other options.

These are not merely academic questions for Welsh. When he was looking for a Nashville elementary school for his son, he recalled, he did look at how various institutions’ students tended to perform on standardized tests. He thought they’d tell him something — just not enough, and he had other questions: How diverse was a school? He wanted his son to learn in a multicultural setting and he wanted him to feel like a part of it. Did the school have a heavy-handed track record of suspending Black students? Welsh is Black and his research has led him to be very wary of discipline disparities in American schools.

Last year, a three-year analysis published in American Psychologist found that when students committed minor sins — talking on their cellphone in school or violating a dress code — 26 percent of Black students were suspended at least once, as opposed to just 2 percent of White students. Through his own studies, Welsh has come to see this as “exclusionary discipline” — another way to keep Black students out of classrooms, and in turn, performing less well in school and on tests.

This is one reason that Welsh thinks test scores — despite all the high hopes of data scientists — often fail to give a true portrait of how well a school supports its students. “The question is whether schools are an equalizer, or whether they are replicating inequality,” he said. Test scores, Welsh suggests, won’t tell him that — nor can they reveal whether schools are welcoming places, where students are taught the kind of “joy for learning” that will help them succeed.

Schneider, at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, is currently directing a pilot project in his home state, starting with eight school districts, to look at new ways to measure the quality of a school. He and his colleagues want to see what kind of picture is created by tests that look beyond the standard classroom subjects into what students know about the arts, what they learn from a culturally inclusive curriculum, what they know about the world around them. In this context, surveys with teachers, administrators, and students can provide a better window into how a school is doing. Further, he is experimenting with the idea that writing essays, oral presentations, or performance-based assessments may be better ways to see how students are learning, compared to standardized testing. The goal, he says, is to ultimately replace standardized tests with these more authentic measures of student performance.

In better funded schools, research shows, teachers are less likely to call on minority students in class or recommend them for college prep activities.

Still, it’s unrealistic, Schneider argued, to expect tests to disappear. “Politically speaking, we can’t go from something to nothing,” he said. But testing can be improved, he says, and we can think in much better ways about how it should be used. “A lot of times people talk about the tests being racist. But the deeper problem is the use of the tests,” Schneider said, pointing to instances where parents avoid schools because they don’t like numbers associated with them, or where test scores are used by public officials to force school closures for poor performance. This happens, Schneider said, “even though we know that the scores are really saying that young people are not where they need to be, and we know it’s not necessarily the school.”

Brunn-Bevel, at Fairfield University, has done research that underlines that point. A detailed study she did of public schools in Virginia, using school test data, showed that Black students often outscored their White peers in elementary and middle school in subjects like social studies. But as other nationwide studies showed, Black student scores dropped in high school, where many reported feeling dismissed by teachers. Those poor results were then used to put them on lower academic tracks, which often further depressed their scores.

“Are tests today used to help students? No,” Brunn-Bevel said flatly. “They are used as a system of ranking and sorting.” Like Schneider, she urges not only a realistic picture of what the tests do, but a move toward a more student-centered way of using them.

Also like Schneider, she doesn’t trust the current test model, although her focus is not on school evaluations but on high-powered admissions tests like the SAT. “The idea that the test predicts college success and that it offers a fair assessment has been [called into question] by researchers,” she said. She’s also not a fan of the way the current test system sends a message that four years of college is the only path to a successful life.

This idea also has the support of Vasquez Heilig at the University of Kentucky. He notes that if test data was actually used to direct resources to students and schools who need more help, then we wouldn’t see so many resources directed to already affluent majority White schools. A 2019 report, in fact, found that that majority White school districts receive $23 billion more in funding annually than high-minority school districts, even though they teach almost the same number of students.

Given this, Vasquez Heilig is working with Schneider and other researchers to explore alternative assessment systems. The view of a school or a student offered by a test, he says, is like the airplane window view from 10,000 feet. It’s data, to be sure, but it’s too distant and sweeping to be used for reliable sorting of students, and certainly not as a gatekeeping mechanism for admitting some students to an institution of higher learning and denying that access to others. “Tests should not be used that way,” he said.

The College Board says it is continuing to assess how to improve what its tests measure and how the results are used, and in its emailed statement, officials with the organization emphasized strides made: This year, 1.3 million students nationwide had SAT scores that “affirmed or exceeded” their high school GPA. Of those, “more than 400,000 were African American and Latino, nearly 350,000 were first-generation college goers, and nearly 250,000 were from small towns and rural communities.” In other words, the test gives good students, no matter what their background, a chance to stand out. At the Educational Testing Service, Lawrence adds that test designers there are looking at creating a new complexity of tests, seeking other ways that test-takers can demonstrate competence, in addition to “assessments that are used for high-stakes decisions.

Rosner, though, would like to get rid of the gatekeeper aspect of standardized tests entirely. If we keep tests like the SAT, he argued, we should recognize their limits and — in the same way that advocates are seeking to reform school assessments — we should try to use them in ways that better support both education and all students. And if, as some predict, the U.S. Supreme Court overturns the principles of affirmative action established in Grutter v. Bollinger almost 20 years ago, how tests are used to judge students may become more important than ever.

“Testing, in and of itself, is potentially not that harmful,” Rosner said. “That is, as long as it isn’t used in high stakes decisions.” He’s been working, with some real success, at advocating for test-optional or test-free admissions decisions by colleges and universities, such as the University of California’s last year to drop the SAT/ACT requirement at least through 2025. And he joined with other advocates to lobby the American Bar Association to consider dropping a requirement that the LSAT must be part of a law school application. In November, the ABA’s arm that accredits law schools voted to make the LSAT optional starting in 2025. The full association is scheduled to make a final decision on the tests in February.

If the U.S. wants to move past the troubled history of standardized tests and leave behind their eugenic origins, their use as a segregation tool, and the chorus of criticism about the stubborn cultural problems that plague them — or so a growing consensus argues — it needs to admit that these tests have long served institutions before students, regardless of race or class. Were the tests more student-centric, Rosner and others argue, their primary point would not be gatekeeping, but to offer insights to help with academic success.

“Why not give the numbers to the kids,” Rosner asked, “and let them have the results as good advice?” Wouldn’t that, he wondered, change everything?

LONG DIVISION is an ongoing journalistic project by Undark Magazine, published by the Knight Science Journalism Program at MIT, that examines the fraught legacy of race science.