Burial rites and other forms of grieving the dead possibly date back to the Neanderthals or even an extinct hominid species named Homo naledi. The ancient origins of these important social and emotional rituals for those left behind are still quite a mystery, and anthropologists are still piecing together how these practices have evolved over the course of humanity. With the help of some cutting edge technology, a team from Slovakia, Czech Republic, Belgium, and Austria was able to reconstruct the funerary process of two individuals whose burned remains were uncovered in urns dating back to late in the Bronze Age. The findings were published August 30 in the journal PLoS ONE.

[Related: Composting a human body, explained.]

Scientists studying these processes typically look at two different types of burials—traditional inhumation burials where the deceased is buried and urn burials in which the deceased’s remains are burned and stored in an urn. In many European countries, urn burials from prehistoric times are excavated by archaeologists before heading into the lab for further study.

“For inhumation burials, if you have a complete human skeleton, it is possible to reconstruct a so-called osteobiography—a biography of the deceased individuals based on information obtained from the bones—pretty well,” study co-author and forensic anthropologist Lukas Waltenberger tells PopSci. Waltenberger is currently working at the University of Vienna and the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

According to Waltenberger, scientists can use the pelvis and features from the skull to determine the sex of the deceased, determine the age of death from bone and teeth development, and even theorize a cause of death from evidence of trauma. While the characteristic bone features needed for these kinds of analyses are often destroyed by the fire or during an excavation, scientists are not always completely out of luck.

“It is a modern myth that if a body is cremated, it will turn into ash,” says Waltenberger. “Bone fragments of up to 20 cm [7 inches] in length remain, which contain various information about the life of a person. By reading this information it is possible to tell an individual’s life history even after millenia.”

[Related: This 7th-century teen was buried with serious bling—and we now know what she may have looked like.]

For this study, Waltenberger received complete urn burials from Late Bronze Age Austria (roughly 1400-1300 BCE) that were first uncovered in 2021 and recorded and analyzed all of the material left behind in these urn burial. The interdisciplinary team combined traditional archaeological techniques with anthropology, computed tomography, archaeobotany, zooarchaeology, geochemistry, and isotopic approaches.

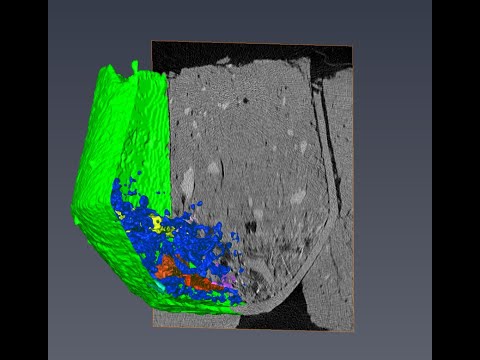

The team first used CT scans to virtually excavate the urns without tampering with them. Eventually, some of the large bone fragments were still recognizable and then started to crumble smaller pieces during the micro-excavation. They then performed osteological (bone) and strontium isotope analysis which revealed details about the individuals whose remains were inside of the urns.

“One urn contained the remains of a young adult female, who died in her twenties, the other one the remains of a 9 to 15 year-old child,” says Waltenberger. “The child showed signs for vitamin deficiencies (Vitamin C and D). So, it was not healthy.”

The isotope analysis revealed that both individuals were born in the present-day St. Pölten area of northeastern Austria area and likely lived there when they died. They also found evidence that both people had been cremated on a pyre with food offerings (meat from sheep or goat and red deer) and bronze jewelry. The female individual was also buried with the tooth fragments of a wild boar, which Waltenberger suspects probably would have been worn as a wristband or necklace. The urn also had traces of eight wild and five crop plant species from the region that were offered up as funeral offerings and used as fire accelerants. According to the team, this is the first known evidence for plant residues in a prehistoric cremation burial.

[Related: Details of life in Bronze Age Mycenae could lie at the bottom of a well.]

In future studies, similar interdisciplinary techniques could be to other urn burials to learn more about their prehistoric inhabitants. The team from this study has started to apply these techniques to a large sample of 1,000 cremation burials.

“First results are very promising and already point towards local variation of funerary rites,” says Waltenberger. “It is possible to receive a comprehensive impression of the Late Bronze Age, if only researchers consider state-of-the-art techniques and look for this tiny traces of information like a detective.”