INSIDE THE Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., there’s a living time capsule. The massive storage facility, run by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division, is filled with wax cylinders, record players, and other pieces of dated audiovisual equipment. Some might see it as a junkyard of outdated technology, but Stephanie Barb likes to call this place the “land of lost toys.”

“We used to play records all the time,” says Barb, the deputy director of IT service operations at the Library of Congress. Now, owning a record player is almost a whimsy.

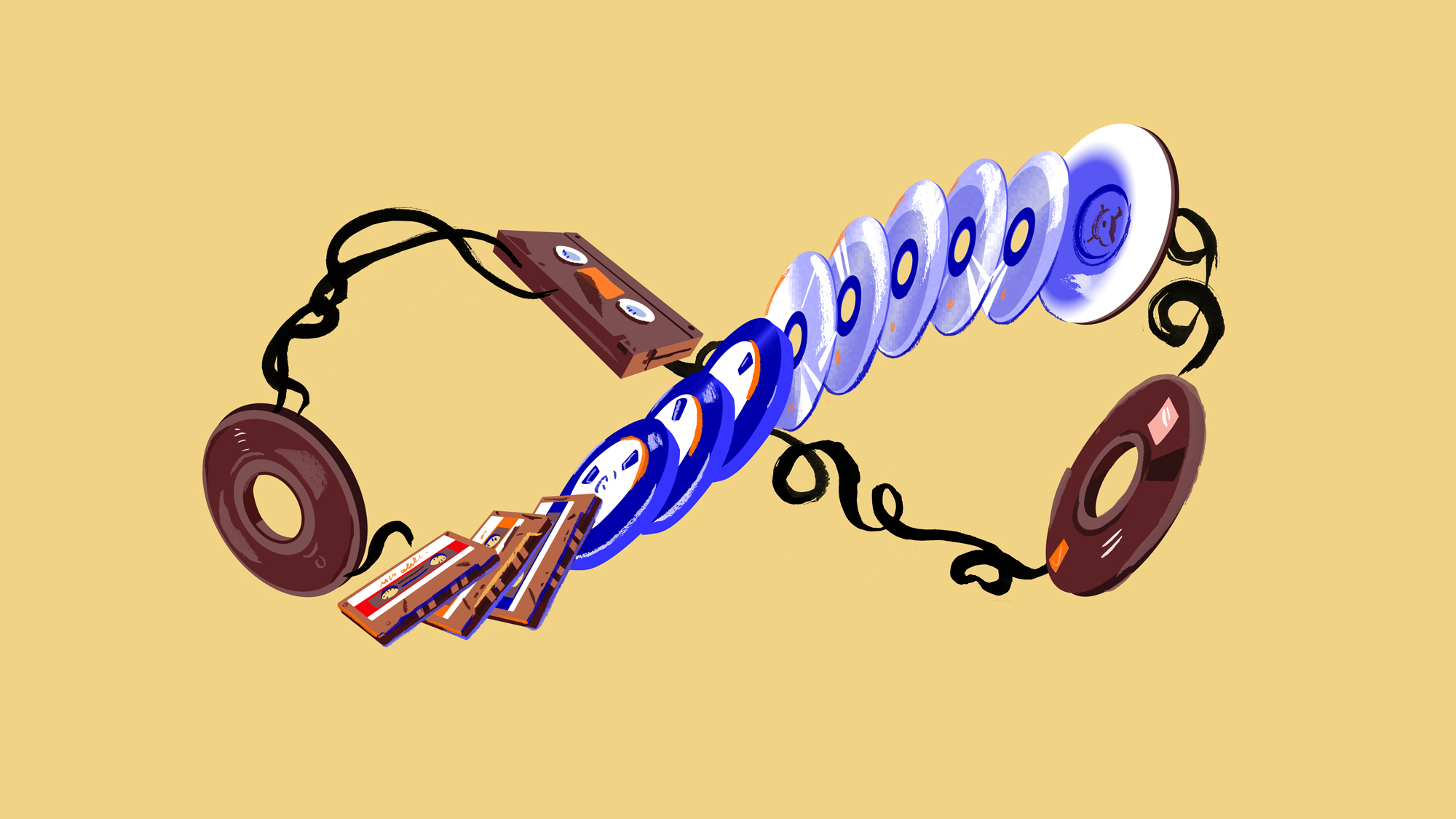

When machines become obsolete, the data they hold can be lost as well. Software and hardware fade out of general use as newer products and services replace them. It’s one of the several roadblocks technicians and archivists like Barb continuously run into in their quest to store information for long-term safekeeping. Right now, experts say there is no one storage device that can save data forever. Options like magnetic tape, Blu-ray Disc, and even DNA may provide stable but relatively temporary storage banks in which data can live while better technologies are tested and brought to market. However, each of these choices has its own shortcomings, and no one method is perfect in terms of both capacity and durability, with new innovations always on the horizon.

The Library of Congress, for example, has a digital footprint of 176,000 terabytes, with its website catalogs of books, photos, videos, and other mediums taking up 5,350 terabytes alone (the equivalent of nearly 2 billion three-minute-long MP3s). Right now, this mountain of data is growing at around 1,500 terabytes a year. Archivists are racing against time to elongate the life of important documents and media.

“Part of the preservation process is keeping operating systems and hardware up to date,” says Natalie Buda Smith, director of digital strategy at the Library of Congress.

Nothing lasts forever

Preserving files in older mediums, like LP records and gaming consoles that have been discontinued, takes a bit of DIY tinkering. At the library, archivists rebuild vintage media players to recover data and transfer it to a more modern form of storage. Sometimes, the team even develops specialized technologies. For example, a system called IRENE, which the library codesigned with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, reads the depths of the grooves in broken phonograph records to convert the music to a digital format.

This is particularly important with the materials eligible for copyright, says Barb. Books can last forever if preserved properly, but items that are submitted for copyright on more corruptible materials, like DVDs, CDs, and DVRs, can degrade over time. “That puts us in a crunch to pull that data off those obsolete technologies and preserve it digitally, because we are going to lose what’s on there,” Barb explains. Since there’s a duplicate provided with every copyright submission, the Library of Congress typically adds it to the collections with the intention to update to a more modern method.

Back up your work

When it comes to preserving data for the future, it’s important to keep the context in which the content exists. “Content says, ‘Here are the bits’; context says, ‘Here’s all the other stuff you need to understand those bits,’” notes Ethan Miller, director emeritus of the National Science Foundation’s Center for Research in Storage Systems. The extra context includes metadata, software, and hardware such as video game emulators. It’s the modern-day equivalent of a Rosetta Stone—a key that gives meaning to written languages and symbols of the past.

A lot of the data currently being collected is “born-digital content” rather than content that had to be digitized, Buda Smith says. Artifacts gathered from internet archiving are good examples. Even though the virtual-first information may ultimately end up on a physical medium like tape, it may live in a variety of other storage forms along the way. Saving multiple backups on different mediums is also good practice.

Held together by tape

The library preserves the majority of its data on a decades-old medium that has so far stood the test of time: simple and affordable magnetic tape. The material is a Goldilocks medium prized for its density, data-writing speeds, and low cost.

Even though tape storage has been around since the mid-1900s, it’s still constantly being improved upon to squeeze more and more bits of data onto each inch of tape. Companies like IBM are working to double capacity per cartridge (to a maximum of 45 terabytes) in newer generations while keeping the format relevant for the future. But tape is not foolproof. If the magnetic strip is damaged or overheated, the data can be wiped out. And while tape is faster to read from and write to than more novel mediums, the data it holds is not as easy to access or edit as information stored on flash drives or hard disk drives (HDDs).

A driving force

The way you use data, and how often, will influence which storage mediums are the best fit. HDDs—the basis of cloud infrastructure—are a good starting solution for small companies with digital collections, says Shawn Brume, IBM’s storage strategist. Take movie studios, for example.

“We are almost 25 years into [the filming of] the Star Wars prequels,” says Brume. “Disney has never moved the raw footage from filming those off of digital technology, and has stated that it will not.” That’s because keeping them on a hard drive makes cutting footage or inserting footage, whenever the filmmakers decide they want to make changes, much easier.

But HDD becomes more expensive with time and scale, Brume adds, making its use a pricey hassle with systems that continuously pump out large batches of data, like autonomous vehicles. The average driverless car system will generate upwards of 400 terabytes a year: If you have millions of cars all doing the same, then companies will easily get crushed by HDDs. Across the industry, the total cost to store a terabyte of data on HDD deep density storage (including infrastructure operations costs) ranges from approximately $0.70 to approximately $0.80 per month, according to Brume. For tape, it’s much less, at approximately $0.08 to $0.12 per month. So with this method, the information will eventually need to be migrated to tape for lower-cost, longer-term, and offline storage. “It’s a process of ingest, collate, coordinate, and copy out to tape,” Brume says.

If you look at history, nothing has been the forever medium except for something that’s chiseled on the wall in a cave

Shawn Brume, IBM’s storage strategist

IBM advises companies on how to move their data from HDDs to long-term tape infrastructure if they will need to retrieve it in the future. But the drawback of tape, unlike hard drives, is that it is pretty hard to alter. You have to erase and rewrite everything even if you want to change just one detail.

The race to make space

An often overlooked contender may soon pull ahead of tape and cloud storage in the eternal-storage race. Many experts agree that Blu-ray, or polycarbonate optical discs, shows immense promise, especially for preserving data for decades, and maybe centuries, in an untouched box. Named after the violet laser in the reader, this system has an edge over flash or hard drives, as the parts don’t wear out, Miller explains.

It all comes down to basic mechanics. HDDs don’t read or write very well after being powered down for a spell. Similarly, flash drives have a limited lifetime. That’s because the electrons in the device’s transistors leak out with use, passing through barriers and altering the charge of the material over months and years. “That means you have to read the flash every so often and rewrite the data,” Miller says.

That’s where Blu-ray can excel. According to Miller, the technology needed to scan the discs is relatively simple in its construction: It’s basically a motor that spins, a reader that goes in and out, and a low-power laser. Optical drives are even simpler than those used for magnetic tapes. A lower price point of $50 to $200 per drive also sweetens the deal.

To Miller, the question of where to store data boils down to the question of what technologies will be available in 100 to 1,000 years to read it—whether from Blu-ray or more experimental forms of storage like glass and DNA.

“If you look at history, nothing has been the forever medium except for something that’s chiseled on the wall in a cave,” Brume says. But even that information corrodes. With every new invention for record-keeping—stone, paper, code—knowledge still had to be passed down and translated to the next place. “We’ve always had to manage data,” he adds. “There’s never been a forever instance of anything.”

Read more PopSci+ stories.