Scientists have identified what happens in our brain when we mimic a foreign accent or impersonate another person, according to a recent study from the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience.

The researchers, led by psychologist Carolyn McGettigan from Royal Holloway University of London, wanted to explore the way the brain controls the non-verbal aspects of our speech–the different tones or styles people use when talking in different contexts, like talking to your boss on the phone versus chatting with a friend in a coffee shop or hitting on someone at a bar.

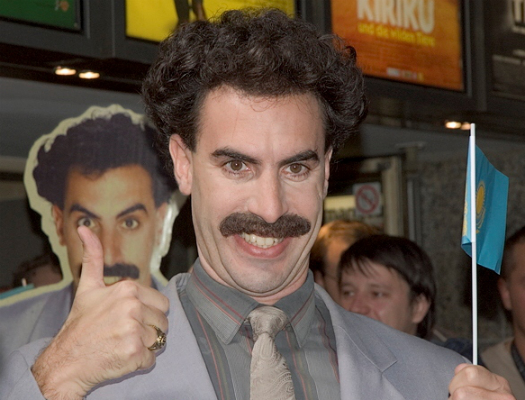

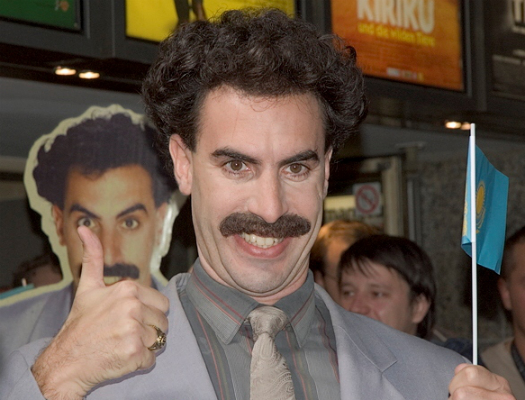

Popular selections included Sean Connery, Elvis and Bill Clinton.

Before the study began, participants–all “non-professional impressionists”–were asked to make a list of 40 different accents and 40 people, from their mother to Arnold Schwarzenegger, they could try to impersonate. They then had to recite a few lines of a nursery rhyme in some of those accents while in an fMRI scanner. (Some popular selections included Sean Connery, Elvis and Bill Clinton.)

When study subjects consciously changed their voices, either with a new accent or during an impersonation, the left anterior insula and the interior frontal gyrus (LIFG), areas associated with planning and producing speech, lit up in fMRI images.

Impressions in particular generated greater responses in other regions of the brain, the posterior superior temporal/inferior parietal cortex and right middle/anterior superior temporal sulcus, but there was no difference in the increase in activity in the LIFG between accent and impersonation planning.

This research “could potentially lead to new treatments for those looking to recover their own vocal identity following brain injury or a stroke,” lead author Carolyn McGettigan explained in a statement. Identifying the regions of the brain involved in controlling the voice could be helpful in treating rare afflictions like Foreign Accent Syndrome, a condition that distorts speech patterns, often after brain damage, giving a person a completely different accent.