Tourists vacationing on the sunny isles of Reunion and Mauritius have no idea what secrets those sandy beaches hold. The islands could be hiding the remains of an ancient micro-continent, quietly torn apart between 50 and 100 million years ago, according to a new study. Scientists think they have spotted a fragment of a continent known as Mauritia.

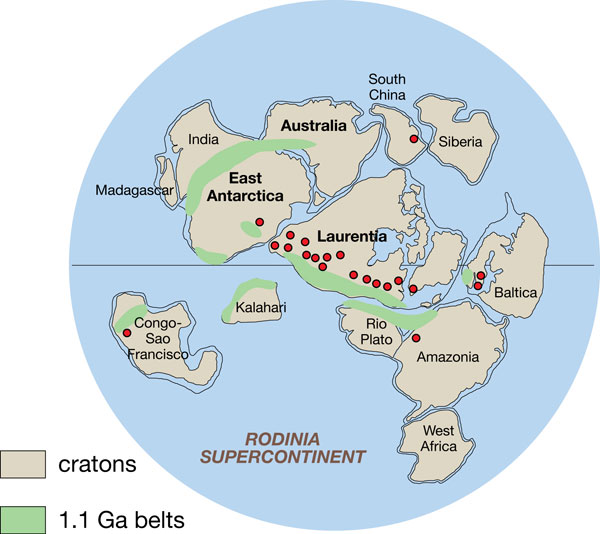

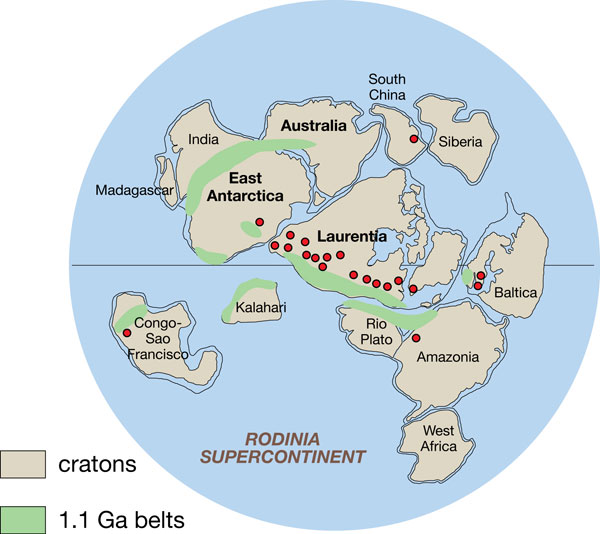

The small strip of continent was once tucked tightly between the lands now known as India and Madagascar, back when those areas were packed into a supercontinent known as Rodinia. (It’s the older and less-famous relative of supercontinent Pangaea.) Evidence of this sandwiched continent came from sand grains on Mauritius beaches, according to Trond Torsvik of the University of Oslo in Norway and colleagues.

Rodinia would have existed from the Precambrian era, about 2 billion years ago, to around 85 million years ago when plate tectonics broke it apart. Continental breakup is usually a mantle plume’s doing–hot rock from within the Earth softens up tectonic plates, which eventually split. This is how the land masses now known as Madagascar, India, Australia and Antarctica broke up and migrated to their current locations on the planet. As this took place and the Indian Ocean formed, small fragments located on the edges of the rupture zone broke off–this is how the Seychelles came to be. Mini-continent Mauritius just wasn’t so lucky, and it slipped beneath the waves, disappearing with time.

Much later, volcano eruptions spewed its remnants back to the top of the Earth’s crust, Torsvik and colleagues write.

They examined sands in Mauritius that formed from eroded volcanic rocks, dating to about 9 million years ago. But when the team looked at these sand grains, they found ancient zircon minerals that were far more ancient–between 660 and 1,970 million years old. The presence of these ancient zircons points to microcontinent fragments churning up due to more recent volcanic activity, the team says.

The discovery of a possible microcontinent fragment suggests continental leftovers like the Seychelles might be more common than scientists thought. A paper describing the research is published this week in Nature Geoscience.