You already know the most famous example of TV influencing a debate: Nixon sweating under the heatlamps, looking browbeaten, unpresidential, while squaring off against Kennedy. But even that touchstone might be something of an American political folktale. So with a new pair of candidates set to face each other down tonight, it’s worth wondering what, if any, effect TV has on debates. However you feel about the candidates, one thing’s for sure: Your opinion is a flip-flopper.

Consider “the worm,” that little audience-feedback EKG you might have seen from other debates or events.

The line is a measurement of audience engagement and approval, going up or down depending on feedback from the crowd. It’s an interesting idea–we don’t even have to wait until the debate is over to tell our candidates what we think–but the problem is, it’s a bad representation of what we actually think. In a 2011 study, researchers decided to rig the worm. They took 150 voters and exposed them to it during a UK election debate. Gordon Brown got a bump in positive feedback for one group, Nick Clegg in another, and David Cameron didn’t get any kind of a bump. That line on the screen was enough to change perceptions of winners, and even enough to change who they intended to vote for.

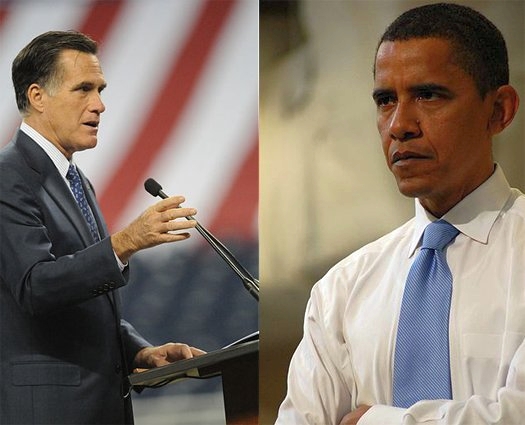

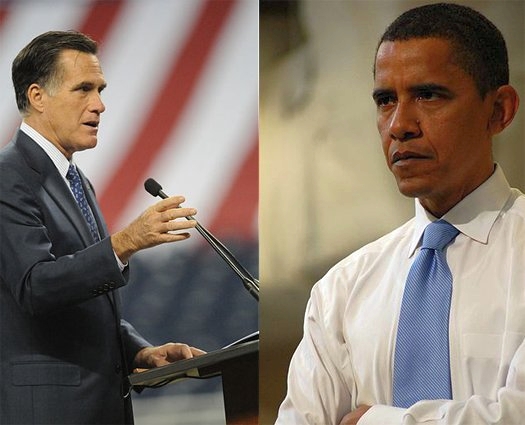

In another study, reminiscent of the Nixon-Kennedy legend, researchers studied attitudes of HDTV-owners toward candidates in the second debate of the 2008 election. They found that viewers reacted more negatively to John McCain than Barack Obama, and even freely cited McCain’s age as a negative factor. On a regular TV, presentation matters, too: Yet another study found that a split-screen view of the debate (versus a full-screen view) made viewers more likely to value party affiliation in their choices, but also to rely “less on pre-existing notions when forming opinions of the debated issue.”

If you’re the type that favors media brainwashing-conspiracy theories, you could while away plenty of afternoons counting the ways television can be used to change opinions on political debates. But there’s a big difference between opinions shifting and the results of an entire election shifting. The person the public crowns the winner of the debates isn’t necessarily going to end up taking the oath of office. As Journalist’s Resource points out, debates are, charitably, not all that important. (The site also has a curated list of these studies and others related to it.) They’re not the only ones, either: The New York Times’ Nate Silver culled the data and ruled that debates have “a modest impact,” while a recent Washington Monthly story was much warier of debates being “gamechangers.” It wouldn’t be unfair to say the consensus is this: TV can change opinions on debates, but at best, debates only move the needle a small amount.

No need to adjust your set.