There is a hint of magic in every bottle of Glenfiddich Single Malt Scotch Whisky. The way it is crafted is the result of a bond between science and art that dates all the way back to 1887 when the first drops of Glenfiddich flowed from the stills. From malting, mashing and fermenting to distillation, aging and bottling, each step is carefully monitored by experts who have worked at the Glenfiddich Distillery for decades. While every part of the whisky making process is important, the aging process is where the spirit truly realizes its character.

At its family-owned and operated distillery, Glenfiddich still ages its whisky using their traditional combination of both American and European oak casks. New make spirit flows into the oak casks seeping into the billions of microscopic pores, extracting over 70 separate flavors and aroma compounds from the wood. The spirit picks up sweet vanillin’s and furfural and maltol which give notes of caramel. The European casks contribute more tannins and give a deep red tint to the whisky.

Whisky aging in Scotland is a steady, slow process. Though it depends on atmospheric conditions, most single malts age for at least a decade. The youngest whisky in the Glenfiddich range matures in oak barrels for at least 12 years while the oldest ages for an incredible 50 years. The same network of pores and capillary action that allows the whisky soak into the wood also allows the spirit to soak out of the wood. Whisky pulled to the outside surface of the barrel evaporates, resulting in the loss of water and alcohol over time. The whisky lost this way is affectionately known as “the angel’s share.”

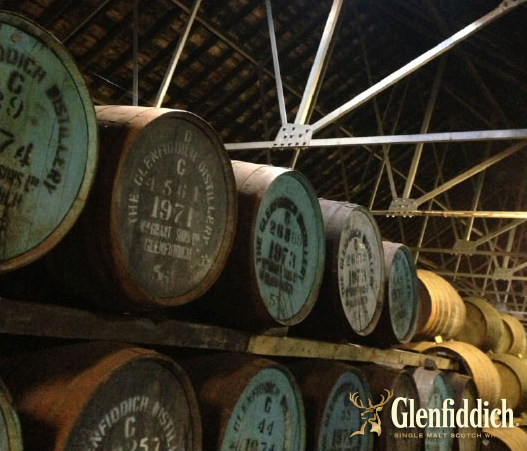

As a general rule of thumb, the hotter the ambient temperature is, the faster a whisky ages and the more it loses to the angel’s share. The ambient humidity determines whether the loss is more water or more alcohol. Although many Scotch distilleries now age their product off-site somewhere in the central belt of Scotland, Glenfiddich still matures its whiskies on-site in one of their forty-six warehouses at Dufftown, located in the north of Scotland. Consequently, they have a relatively even, moderately temperate climate that helps maintain consistency of product year-round.

The rarest and most precious Glenfiddich vintages are matured in traditional dunnage warehouses, which eschew modern climate control systems for traditional building materials like low slate roofs, thick stone walls, and soil floors. These elements combined with the absence of any windows mean dunnage warehouses are less prone to seasonal changes and help regulate the humidity. The dunnage warehouses are much smaller and lower, than the modern, concrete-and-steel palletized warehouse, which allows the warehousemen a finer and more consistent control of the finished product although it does require that each cask is moved by hand as no machinery is able to operate in these traditional warehouses.

On average, a barrel of maturing Glenfiddich will lose about 2% of volume per year of aging, more of it alcohol than water. That means that every year, a cask loses the equivalent of five bottles of cask-strength whisky. With thousands of casks in each of their 46 warehouses, you can do the math to get some idea of how well the angels of Dufftown drink. It could be worse—some American whiskies, aged in the scorching heat of the American South, can easily lose around 15% of a cask by volume to the angel’s share every year. During especially warm summers that figure can jump to as high as 25%. In any case, the angel’s share is a necessary part of the whisky making process.

That’s why, even though evaporated whisky is evaporated profit, the master whisky makers of Glenfiddich will talk fondly about the angel’s share. They say that keeping the whisky flowing keeps the angels smiling and with more and more people enjoying Glenfiddich around the world every year, one can hardly begrudge them.