This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

A curtain of white vapor blurred the outline of Alessandro Santi as he bent over the edge of a gray bubbling pond in Pozzuoli, a city in southern Italy. In the thick sulfurous cloud, the 30-year-old technician dipped a six-foot pole, the end of which was attached to a plastic cup, into the 180-degree Fahrenheit water and pulled back a sample. He turned around and carefully poured the water into a glass container.

Underneath his feet, one of the world’s most dangerous volcanoes lay dormant. While many people have heard of nearby Vesuvius, which wiped out Pompeii in 79 AD, far fewer are familiar with this underground threat.

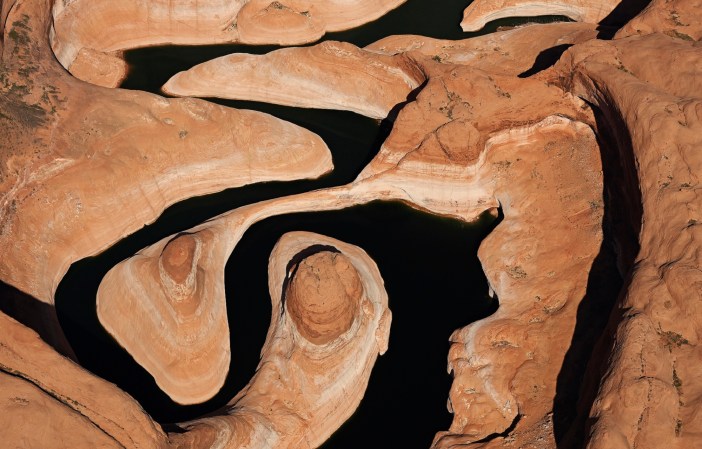

Santi was doing field research in a large circular depression—or caldera, created when a volcano explodes and collapses—that measures up to 9 miles across. The caldera, known as the Phlegraean Fields, is part of a larger stretch of mostly underground and undersea volcanos that run along the Italian coast.

The last two major Phlegraean (pronounced FLEG-rian) eruptions occurred about 40,000 and 15,000 years ago. They annihilated most life forms in the region and sent ashes all the way to Russia. Scientists today are worried about the consequences of another eruption, now that around half a million people have built their homes, vineyards, schools, and roads just above this unstable terrain.

Over the past 18 years, the ground level in Pozzuoli has risen by about 43 inches, and it’s not uncommon for local residents to wake up to sudden sounds and vibrations from the Earth’s bowels. The frequency of earthquakes has been rising, and in 2012, the Italian Civil Protection Department, which is responsible for preventing and managing emergencies, raised its level of alertness from green to yellow. This signaled a need for greater attention and resources to monitor the caldera. Scientists know that something is happening down below, but they’re not exactly sure what.

“The catch is that we can’t go down directly” to check, said Santi. Instead, local researchers sample and measure what they can access, including water from the pond and gases from fumaroles, or vents. The samples carry traces of carbon dioxide, methane, and hydrochloric acid, among other chemicals, which originate far below the pond’s muddy bottom. Changes in the levels of these substances might signal danger, such as the imminent arrival of magma.

The water sampling is part of a greater routine effort by the Naples Center of Italy’s National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, known as the Vesuvian Observatory, which hosts intricate seismic monitoring systems and works with pioneering technology to monitor the volcano. Through dozens of on-field and underwater monitoring sites, the center is keeping the pulse of the caldera; it’s ready to alert Italy’s Civil Protection Department, which has been planning mass evacuations if things go south.

Scientists today are worried about the consequences of another eruption, now that around half a million people have built their homes, vineyards, schools, and roads just above this unstable terrain.

The effectiveness of such an emergency operation would likely depend upon the willingness of local residents to follow orders. “Collaboration between different stakeholders and residents is crucial,” said Rosella Nave, a researcher at the Vesuvian Observatory, “both in planning and managing a crisis.” According to several studies, many living on top of the caldera don’t perceive it as a salient threat. Instead, older generations remain haunted by past mismanaged evacuations, which brought significant economic losses to the local community. Other residents, meanwhile, are more worried, and do not trust the Civil Protection Department to respond effectively in an emergency. Some residents have responded to minor earthquakes in ways that would prevent the smooth execution of a formal evacuation plan, said longtime Pozzuoli resident Anna Peluso, who runs a Facebook group that discusses the volcano monitoring and evacuation plans.

A massive explosion is unlikely to happen anytime soon, scientists say, but smaller eruptions would not come as a surprise: There have been 23 in the past 5,500 years. And because the bay is now densely populated, even a relatively weak burst could turn into a catastrophe.

The Italian peninsula sits atop the border where the Eurasian and African tectonic plates meet. As the African plate dives under the Eurasian one, it stretches part of the Eurasian plate thin, like a pizza dough. According to Mauro Di Vito, a volcanologist and the director of the Vesuvian Observatory, this complex movement sends fresh magma — molten rock below the Earth’s surface — to Italy’s 12 active volcanoes. (Magma that breaches the Earth’s surface is referred to as “lava.”)

Since Ancient Roman times, the Phlegraean Fields have experienced periods of what’s known as bradyseism: the steady uplift or descent of the Earth’s surface. (The term derives from a combination of the Greek words for “slow” and “movement,” and is pronounced BRADY-size-um.) Yet because the region lacks a mountainous landform—something resembling, say, Mount Saint Helens in Washington State, or Mount Fuji, just outside of Tokyo, Japan—few suspected the presence of an active volcano. This began to change in the 1950s, when a Swiss scientist conducting field work in Italy hypothesized that the Phlegraean Fields were part of a caldera.

Over the next decades, geophysicists began to monitor the area. In 2008, a team of researchers identified a sizeable magmatic reservoir about 5 miles underneath Pozzuoli, and smaller pockets of magma exist a bit higher in the crust, Di Vito said. Heat and gases from the fiery underground reservoir create pressure that cracks the layers of rock above; around 2 miles above those cracks, at the Earth’s surface, people feel the movement as an earthquake.

Within the volcanic scientific community, there are varying lines of thought on the future of the Phlegraean Fields. Some say that the current earthquakes and ground uplift stem just from the release of gases from the reservoir and the area’s hydrothermal system. Therefore, it’s possible that the ground will eventually deflate and earthquakes will diminish. Others say that the movement of magma in past decades has weakened the Earth’s crust, making it more likely to rupture than previously thought. In this case, were the magma to reach the surface, things could get nasty: An eruption could potentially destroy the 5 cities plus the part of Naples that all sit on top of the caldera.

The lack of consensus stems from a basic problem in volcanology: Scientists have yet to develop an approach that can precisely predict future eruptions. While the presence of magmatic gases in the caldera’s fumaroles might signal the imminent arrival of an eruption, there’s no good way to predict an eruption a year or months in advance.

In 2017, Christopher Kilburn, a professor of volcanology at University College London, co-published a study with Vesuvian Observatory scientists in Nature Communications that caught the attention of the Italian media. While it had been previously thought that periods of relatively fast ground uplift in the Naples region were followed by relaxation of the Earth’s crust, the paper suggested that the crust is actually accumulating the stress. “With each episode of unrest, uplift, the chances are we’re getting closer to the possibility of breaking the crust,” Kilburn told Undark.

In June, Kilburn and his colleagues published a follow-up study, which found that, around 2020, the pattern of earthquakes caused by the volcano had changed, leading the team to conclude that the Earth’s crust was becoming weaker over time, and more prone to rupturing.

According to Kilburn, signs of an imminent eruption could be very subtle. This is what happened at the Rabaul caldera in Papua New Guinea, he said. There, a couple years of intense seismic activity was followed by a 10-year period of relative stillness, Kilburn said. Then, suddenly, in September 1994, after only 27 hours of unrest, the volcano erupted, devastating the town of Rabaul.

Although there is no way to know that the same thing will happen in the Phlegraean Fields, Kilburn stressed, the findings show how the Earth’s crust could break without much extra pressure, which is something to consider for evacuation plans.

“With each episode of unrest, uplift, the chances are we’re getting closer to the possibility of breaking the crust,” Kilburn told Undark.

Previous disasters have resulted in criminal lawsuits for scientists and government decision makers seeking to keep people safe. After an earthquake in central Italy killed 309 people in 2009, seven Italian experts were convicted of manslaughter for carrying out what was deemed to be a superficial risk analysis and for providing false reassurances to the public.

The defendants were sentenced to six years of jail, though all but one was eventually acquitted.

When asked about this lawsuit, Di Vito said that earthquakes cannot be predicted like eruptions of a well-monitored volcano, and that multiple government decision makers are involved in monitoring and assessing risk at a volcano site. “In the case of the emergency in a volcanic area, the situation is quite different.” But still, he added, the 2009 earthquake was a “lesson for Civil Protection and for scientists.”

In 1970, Eleonora Puntillo, then a Naples-based journalist, noticed something strange happening at the Pozzuoli harbor. When people disembarked from ferries, they had to step up to the pier; in the past, they’d had to step down.

“Either the sea had subsided, or the earth had risen,” the 84-year-old reporter recently told Undark. She started investigating and confirmed with local residents that the ground had indeed risen and damaged several buildings, but surprisingly, scientists were not doing much to monitor the likely cause of this bradyseism: the caldera, part of which sits directly below the harbor.

Puntillo knew that in 1538, the Monte Nuovo volcano had erupted, spitting ash and magma just a few miles from Pozzuoli’s old city center. Back then, the soil had risen, accompanied by a series of scary earthquakes. Puntillo connected the dots and published an article headlined “The Sea Retreats, The Volcano Boils,” reminding the community that a similar phenomenon had occurred in their region half a millennium earlier.

“I wish I had never done that,” Puntillo said, recalling how hordes of journalists had rushed to Pozzuoli and asked her where the next volcano would pop up. They wrote stories with terrifying headlines that made the community panic. A few days later, residents of the Rione Terra neighborhood, which had experienced much of the lift, woke up and discovered hundreds of soldiers had arrived to evacuate thousands of people from the area.

Heartbreaking scenes followed, with forceful evictions, mothers carrying mattresses, and children in tears. Panic spread, and residents outside the Rione Terra neighborhood also fled. According to The New York Times, at least 30,000 people evacuated Pozzuoli. “I still get goosebumps today at the sight of that terrifying escape,” Puntillo said. In her view, there was no need for the government’s use of force.

Ultimately, the dramatic shifting of the earth lasted two more years, but the volcano did not erupt. Residents of Rione Terra were never allowed to return to their homes and were moved permanently to a different neighborhood inside the caldera.

Residents of Pozzuoli now have generational memories of lost homes, businesses, and livelihoods — not due to a volcano throwing rocks into the sky, but due to the Italian state that evicted them. “We have bradyseism in our blood,” said Giuseppe Minieri, the 53-year-old owner of Pozzuoli’s A’ Scalinatella restaurant. “We were born here.”

Antonio Isabettini, a painter who has portrayed the Phlegraean Fields from countless angles, stood on his home’s balcony in the run-down Rione Toiano, which was given to his parents by the state in the 70s after they left Rione Terra, a move they had been planning prior to the evacuation. He pointed his finger toward the ground and said, “I’m standing on this plane, which is actually a volcano. What do I do? Should I leave?” Before moving there, he lived for 15 years in an apartment building bordering the Solfatara, a volcanic crater that constantly emits steam and sulfur fumes.

“We co-live with this; we know this is a dancing land; we know that there is a magmatic chamber down here,” he said. But if the entire caldera were to erupt like it did millennia ago, he added, it would be disastrous.

On the third floor of the Vesuvian Observatory, Mario Castellano stood in front of a dozens of computer screens that display data arriving from more than 60 permanent monitoring stations on the Phlegraean Fields. A 2.8 magnitude earthquake had been recorded the night before.

“If there is a strong earthquake, we notify the Civil Protection,” said Castellano, the technologist director at the control center. Over the past 17 years, Castellano said he has witnessed a steady increase in the number and magnitude of earthquakes.

In addition to using seismometers to record the Earth’s vibrations, the observatory’s scientists use both land and custom-designed marine GPS stations to detect what are known as land deformations, places where the ground has risen or fallen due to pressure from underground gases or magma. Additionally, instruments called tiltmeters measure subtle shifts in ground slope. This constant flow of data is crucial to detecting the upward movement of magma quickly, said Prospero De Martino, the scientist in charge of monitoring land deformations.

De Martino has noticed an increase in ground lifting speed, but scientists aren’t certain what is causing it: Gases? Magma? Either way, such a dramatic change in the Earth’s surface is enough to worry De Martino.

The researchers compile the monitoring data into a bulletin, which is published every Tuesday on the observatory’s website and social media platforms, so the public can stay informed on the state of the volcano. Occasionally, the observatory receives phone calls from concerned residents asking when and where they should evacuate—advice that only the Civil Protection Department can give, not the scientists.

For people living in the caldera, attitudes around the threat the Phlegraean Fields pose have, in certain ways, been changing. In a survey conducted in 2006, most study participants viewed an eruption of Mount Vesuvius as a danger, despite the fact that scientists say an imminent eruption there is highly unlikely. These same individuals didn’t know much about the volcano underneath their feet. Additionally, people reported having little trust in local authorities to manage a volcanic emergency.

These findings prompted the observatory and the area’s municipalities to undertake an educational campaign to create awareness of the caldera. They gave talks in schools, public offices, and city squares. In 2019, Nave and her team conducted a follow-up study to see if volcanic risk perception had changed over time. Although the study has not yet been published, preliminary findings suggest that 37 percent of locals still fear Vesuvius above all (though this has dropped from 70 percent in the 2006 survey), and the level of trust in a governmental response remains minimal. The survey also revealed that that most local residents don’t list the volcano as among the top seven problems in their community.

“We have bradyseism in our blood,” said Giuseppe Minieri. “We were born here.”

However, 60 percent of those surveyed recognized the Phlegraean Fields as the more threatening volcano, and more locals are aware of the emergency plans than they were in 2006. “Residents’ awareness of volcanic hazards is higher now,” Nave wrote in an email to Undark.

Perhaps paradoxically, some residents believe the caldera could explode without any warning signs at all, a scenario that no scientists have hypothesized.

Some researchers aren’t surprised by the reaction. In fact, the perception of panic “is institutionalized by emergency plans,” said Francesco Santoianni, who spent 40 years working at the local Civil Protection Department office. It is “criminal,” he said, that evacuation exercises “are carried out as if the only solution is to escape as far and as quickly as possible.” He recalled one exercise in which volunteers showed citizens how to escape through windows.

Antonio Ricciardi, a geologist monitoring the Phlegraean Fields and other volcanoes from the national headquarters of the Civil Protection Department in Rome, said that Italy’s prime minister, advised by the Major Risks Commission and the head of Civil Protection, will declare what is called a pre-alarm status only if things get really bad: thousands of earthquakes per day; the ground deforming and tilting significantly; an abundance of gases laced with carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide—a sign that magma is about to surface; cracks in the streets and broken pipes. Under these circumstances, the government will empty hospitals and prisons, and cultural assets will be moved or wrapped up to withstand the heat. Some locals will start leaving the area of their own volition, scared by the mayhem. If things worsen, a full emergency status, called the “alarm phase,” will kick in.

It will take 72 hours to evacuate all half-a-million people living in the danger zone, said Antonella Scalzo, a geologist at the Civil Protection Department who is involved with planning and handling a Phlegraean Fields emergency. The evacuation goal, she added, is to make sure that nobody is there if the volcano erupts. Anyone who remains could find themselves in the path of a violent river of gases and volcanic material after an eruption, moving at hundreds of miles per hour with temperatures several hundred to over 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

During the emergency phase, people should know which roads to take to evacuate the area. If they do not want to leave independently, public transportation will carry them to safety, said Scalzo.

“We have to do a lot of work to make people accept that, not today, not tomorrow, but maybe one day, they will be asked to vacate their home indefinitely,” Nave said. Otherwise, “if you don’t go, you’ll end up like a Pompeian.”

Not everyone needs to be persuaded. Many people will evacuate on their own at the first signs of an imminent eruption, Anna Peluso, the longtime Pozzuoli resident, wrote to Undark. She also pointed to one 2015 earthquake, when parents rushed to school to retrieve their children instead of waiting for the announcement of an evacuation, as per the government’s plan. The additional cars on the road paralyzed the city’s traffic.

“Something is happening. Something has changed,” said Peluso. As she walked along a pier, she pointed to roughly a dozen boats, which floated well below the dock to which they were secured.

Next, she stopped at the nearby port, which was empty of water and where small fishing boats almost touched the seabed—clear signs that the earth has risen. Heading away from the sea and into the city center, she passed buildings showing signs of cracks and wear. One four-story residence was missing chunks of earthy red paint and plaster, and fissures ran along its façade.

Many of Peluso’s neighbors, she said, have dismissed her as an alarmist for openly talking about the volcano. But she said she doesn’t care. What worries her instead are the unanswered questions: What is the underlying cause of the increased ground uplift? Will the observatory detect dangerous changes in volcanic activity? And if an evacuation occurs—when will authorities let residents return to their homes?

Before going home, Peluso stopped along her walk and noted that a volcanic crater could “open up right here, in the middle of the street.”

Then she turned to look at the sea. The sunset had painted the water with a calming orange tint. A rocky coastline hugged the harbor. “When somebody asks, ‘Why do you live in Pozzuoli?’” she said, “the answer is right there.”

Agostino Petroni is a journalist, author, and a 2021 Pulitzer Center Reporting Fellow. His work appears in a number of outlets, including National Geographic, BBC, and The Washington Post.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.