There is an enormous and serpentine new concrete-lined tunnel beneath London. For most of its 15.5-mile journey, it mirrors the curves of the River Thames, lurking as a subterranean shadow of the famous waterway, but well beneath it. Its job, when it’s up and running, won’t be to serve as a transit system for subway trains, or vehicles, or people—although a BBC reporter has biked in it and a composer has played the cello in it.

Its purpose will be to carry a huge amount of sewage and wastewater, and if its impressive specs are any indication, it will do an excellent job at that stinky but important task. And in the process, if all works according to plan, it will result in a much cleaner Thames. Here’s what to know about this engineering feat beneath London.

The problem: sewage in the Thames

Like other cities, London has a sewer system that combines both rainwater runoff and sewage from homes and businesses. The system dates to the 1860s; Londoners can thank Joseph Bazalgette for the sewer’s creation, which followed an unpleasant event in 1858 called the Great Stink.

“He designed the system to cope with a population of four million people,” says Taylor Geall, the communications manager with Tideway, the company building the new sewer. “Now, the population is nine million.”

Here’s the problem. A combined system can work well if it doesn’t rain very hard. But if it does, the pipes become maxed out, and the runoff water and the sewage still need to go somewhere. In this case, it intentionally goes into the Thames, at spots called combined sewer overflows, or CSOs.

[Related: The tallest building in the world remains unchallenged—for now]

Untreated sewage spewing into a river is never a good thing, and the more it happens, the worse the situation is. “Back in Bazalgette’s day, that happened quite infrequently,” Geall says. “But now, because we’ve paved over so much, and the population is so much higher, that it only takes a small amount of rain for the system to fill up. And rather than the system backing up into homes, and streets, etcetera, there are outfalls in the river wall and so it gets poured directly into the Thames, and that’s like untreated sewage and rainwater.” Those outfalls are the CSOs.

Geall says that annually, an estimated 44 million tons of rainwater and sewage flow into the Thames. Deborah Leach, the CEO of the environmental group Thames21, provides a similar estimate for the total spillage: around 43 million tons. “Sewage is a huge component of it,” she says. “We’re not just talking the odd little bit of dirt here and there—it’s massive.”

With that discharge comes problems. “We are still seeing these stinking foreshores that you last saw back in Victorian times,” Leach says. “It makes it a horrible place to be.”

And of course, pollution takes a toll on wildlife. “It’s just heartbreaking to see the fish kills coming down the river sometimes,” she adds. That typically happens in June, because sewage-eating bacteria in the water cause “clouds” of the river to become deoxygenated, she says. “They come to the surface—you can see them gasping to breathe.”

Then there are wet wipes, which like the sewage and rainwater flow into the river through the overflow outlets. “We’ve got big mounds of them in the River Thames,” says Leach. “They’re horrible.”

One place where the wipes congregate is near west London’s Hammersmith Bridge. “You can see layer upon layer upon layer of wet wipes, building up,” she adds. “It’s just disgusting.”

London is not alone with this type of problem. New York City features a sewer network that is approximately 60 percent the combined type, meaning that sewage spills into the waterways when the system is overwhelmed. And Paris is dealing with something similar, aiming to make the Seine cleaner before the Olympics in 2024. That infrastructure project involves a tank for rainwater that Time describes as “mammoth.”

The solution: a gigantic tunnel, and other infrastructure

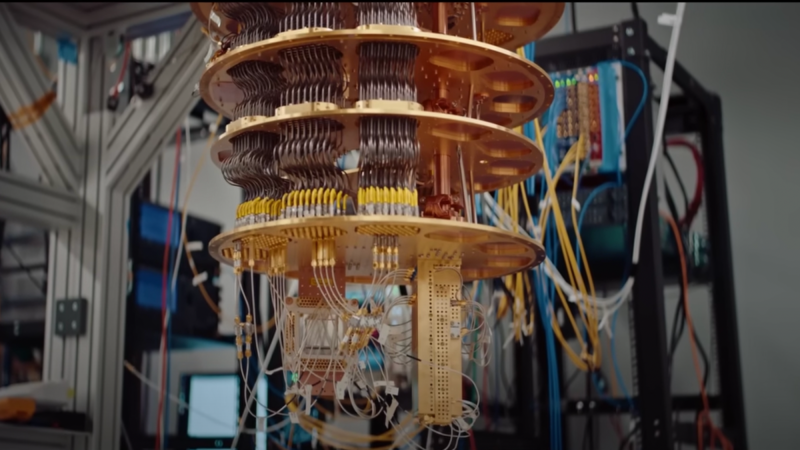

The centerpiece of the London project is the massive main tunnel, which is about 15 miles long and slopes gently downwards from west to east, an incline that means its contents will also flow eastward. Incredibly, the tunnel has an internal diameter of nearly 24 feet across, and in the east, where it’s deepest, it’s about 217 feet below the surface. “It is ridiculously big,” says Geall, of Tideway. “It’s a strange environment to be in.”

But the sewage and rainwater and wet wipes will be right at home. In addition to the main tunnel, other infrastructure will intercept more than two dozen of the combined sewer overflow points and channel the liquid from them into the big winding tunnel deep below London. In other words, instead of going into the Thames, it’ll go into the new sewer system. Once it’s in there, the crap will all flow eastwards. Its final destination is a big facility called Beckton Sewage Treatment Works. The Super Sewer doesn’t replace Bazalgette’s original creation; it augments it.

The tunnel is not up and running yet, but once it is, the company estimates that the 44 million tons of rainwater and sewage that spill into the Thames annually will be reduced by 95 percent. Geall says that the entire system altogether, which includes the main tunnel and shafts, has a capacity to hold about 56.5 million cubic feet of liquid, or 422.7 million gallons.

The total cost of the project, he says, is 4.5 billion pounds, which is around 5.6 billion US dollars. Meanwhile, the company faced criticism last year for the high salary its CEO is being paid.

The project is about 85 to 90 percent complete, according to Geall, and even if it doesn’t officially wrap up until 2025, he says that in 2024 they’ll begin testing diverting flow away from the river and into the tunnel. “In reality, the Thames will begin to be protected next year,” he says.

Leach, of Thames21, says that she thinks “it can’t come soon enough.”

“A hard engineering solution doesn’t come naturally to an environmental charity, but it’s simply the practical solution that needs to be built,” she adds. “It requires these nature-based solutions and wetlands as well.” In that sense, she highlights the ongoing need for natural additions to the landscape, like additional wetlands and rain gardens.

“I think everyone’s looking forward to seeing the river cleaned up,” she says.

Watch a video about the project, below.