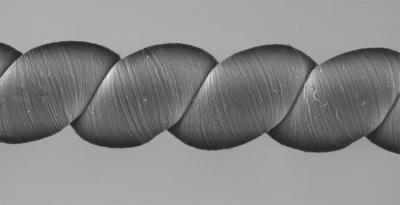

Dionysia tapetodes, an evergreen alpine plant that sports vibrant yellow flowers in the spring, normally lives in tough mountainous conditions. Unlike your typical houseplant, its leaves are small and thick, and grow closely together in a rounded, dome-like shape. The species is also a bit fluffy-looking, says Raymond Wightman, a plant biologist at the University of Cambridge, because it does something quite unusual: Using specialized hair cells, the plant grows a wool-like substance that extends into long strands that stretch across the plants’ leaves “like a spider’s web,” says Wightman.

In a new study published in the journal BMC Plant Biology and coauthored by Wightman, a team of researchers examined what this “wool” is made of, and how the plant makes it.

The researchers used plant samples from the Cambridge University Botanic Garden, which were originally collected from the species’ natural range—which extends from the border of Turkmenistan to mountain regions in Iran and Afghanistan—by a Bristol University professor around 1970. Using a cryo-scanning electron microscope, the researchers flash-froze several leaves and cut them open, which allowed them to catch a glimpse of the hair cells that were producing the wool threads.

The team used a Raman microscope—which fires a laser through a lens, generating a color spectrum that can be analyzed to determine what molecules are there—to figure out the chemical makeup of these wool threads. They identified a substance called “flavone” and two related chemicals. Using another electron microscope, the researchers were able to section even more finely through the leaves.

“And that’s when we saw the holes for the first time,” says Wightman.

Through the electron microscope, they were able to see small holes in the cells’ walls about the same width as the woolly fibers, with a waxy substance outside the cell wall acting as a seal to keep the cell’s contents from spilling out. The plants appeared to be cooking up the woolly fibers inside the hair cells, which were then poking out through these holes in the cell wall.

Holes were surprising, says Wightman, because holes in a plant’s cell membrane typically have catastrophic consequences: “You put holes in cell walls, and they’ll burst.”

Since electron microscopes can only view a sample fixed in time, the team couldn’t actually see the hole-punching in action. The researchers are considering future projects that might provide a better look at how the wool is made. “We’ve not seen anything in biology like it before,” says Wightman.

[Read more: One of the most studied plants in the world can grow an extra organ]

As for why the Dionisia tapetodes makes wool? That’s still a mystery. “When you think about the limited resources a mountain plant has”—they often don’t get much water, for example, and have to make do with nutrient-poor soil and higher UV exposure—“it’s a lot of effort to be making this wool,” says Wightman. The researchers speculate that it could be serving as a kind of sunblock to protect the plants from high-altitude rays, since a related plant that doesn’t produce the wool tends to dry out more easily in the summer.

“I think plants are the best chemists and always will be,” says Wightman. “And they’re going to continue to amaze us.”