Despite not exactly being world-renowned swimmers, pigs have spread across the Asia-Pacific region for thousands of years. But how? With the genetic and archeological data from over 700 pigs, a team of scientists documented how people helped the mammals make their way across thousands of miles. Their findings are detailed in a study recently published in the journal Science.

“This research reveals what happens when people transport animals enormous distances, across one of the world’s most fundamental natural boundaries,” evolutionary geneticist and study co-author author Dr. David Stanton of the University of Cardiff and Queen Mary University of London said in a statement. “These movements led to pigs with a melting pot of ancestries. These patterns were technically very difficult to disentangle, but have ultimately helped us understand how and why animals came to be distributed across the Pacific islands.”

Crossing the Wallace Line

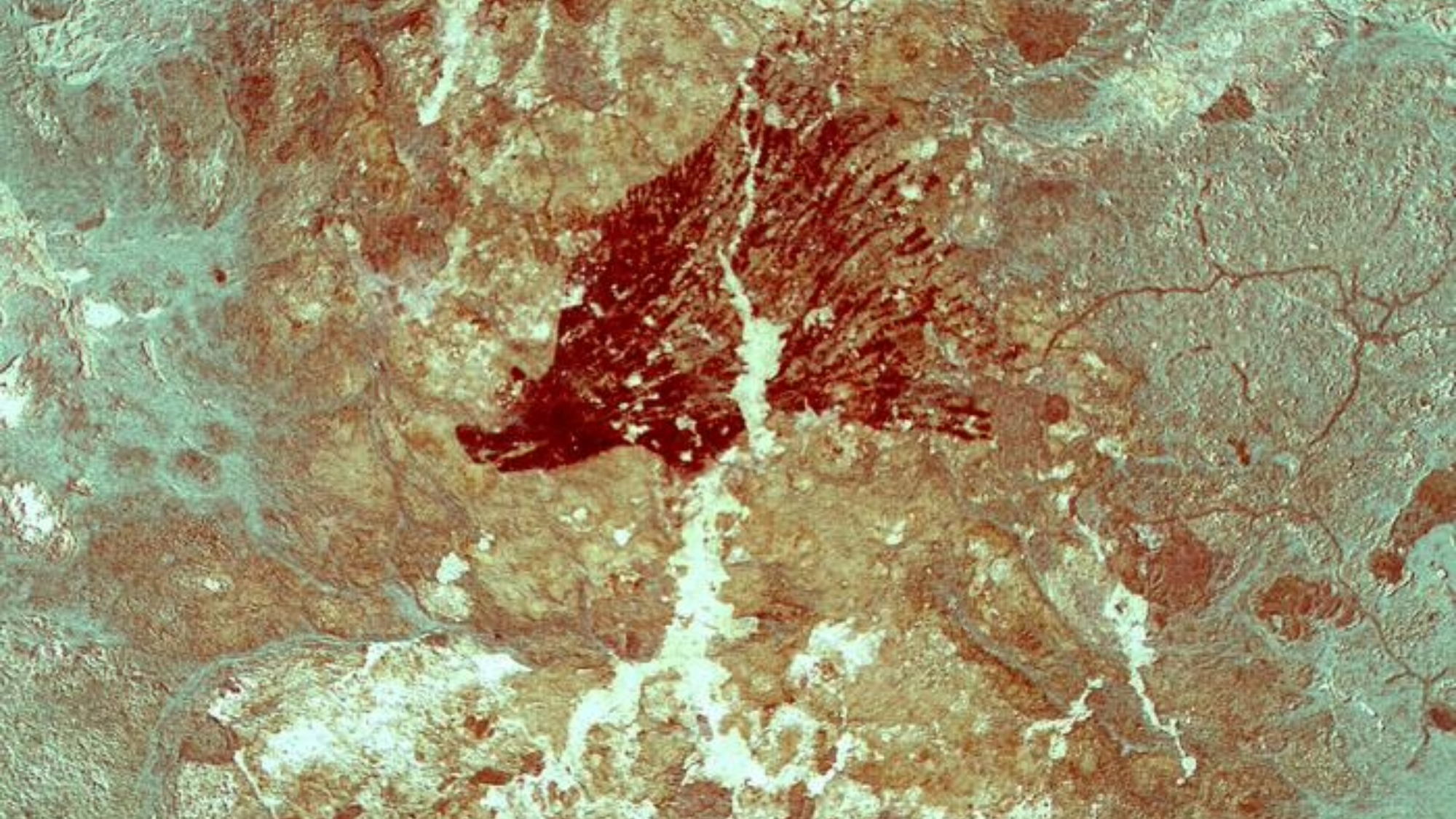

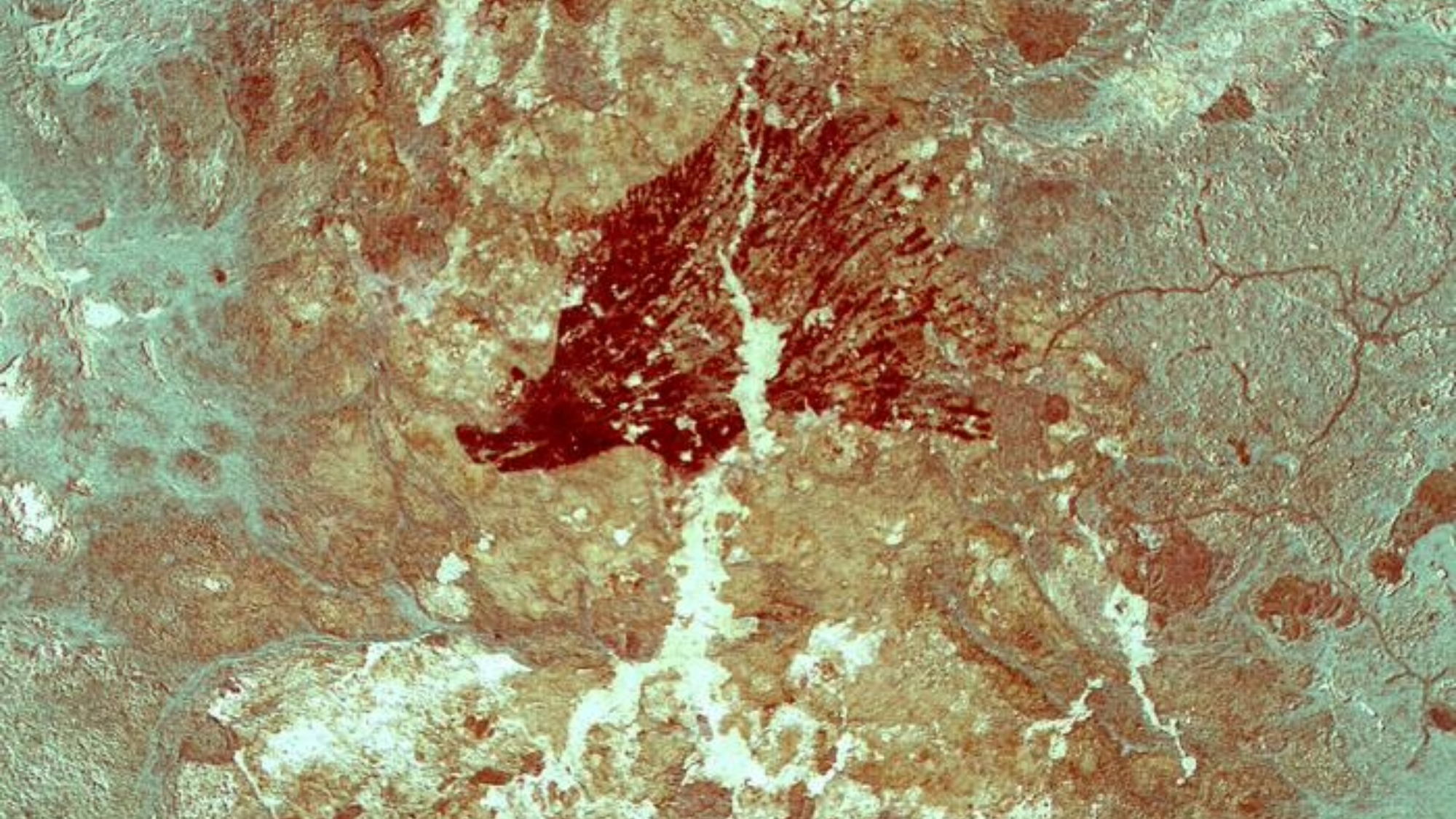

Previously, plants and animals did not always naturally spread across Indonesia’s over 17,000 separate islands. In the mid-19th century, evolutionary biologist Alfred Russel Wallace pinpointed a major biogeographic boundary now known as the Wallace Line. This invisible line stretches from the Indian Ocean through the Lombok Strait (between Bali and Lombok), north through the Makassar Strait (between Borneo and Celebes), and eastward, south of the island of Mindanao, into the Philippine Sea.

Several mammal, bird, and fish groups that are abundantly represented on one side of the Wallace Line are either not represented at all or exist in limited numbers on the other side. For example, leopards and monkeys are found on the Asian side and marsupials are largely limited to the Australasian side.

Pigs represent one notable exception to the rules of the Wallace Line. There are populations of pigs on both sides of the Wallace Line, extending across Southeast Asia into New Caledonia, Vanuatu, and remote Polynesia. The mammals are biologically considered highly effective ecological invaders, and culturally important across the region. Given how well they have established themselves and cultural importance, the role people played in pigs’ spread remains a key question for biologists and conservationists.

“Wild boar dispersed across all of Eurasia and North Africa and certainly don’t need people to help them disperse into new areas. When people have lended a hand, pigs were all too willing to spread out on newly colonised islands in South East Asia and into the Pacific,” added study co-author and University of Oxford bioarcheologist Greger Larson.

Movement 50,000 years in the making

In the new study, a team of scientists examined the genome of over 700 pigs, representing both living animals and archaeological specimens. With the genomic data, the team reconstructed the pigs’ movement across southeast Asia and identified when the animals arrived on certain islands and how they may have interbred with various native pig species living there.

They found that people of different cultures have moved pig species throughout the region for millennia. The earliest evidence of the pig exchange comes from people living in Sulawesi as early as 50,000 years ago. Ancient Sulawesi cave painters depicted warty pig species in their art and even transported them over 1,000 miles away in Timor. Moving the pigs to Timor may have been an effort to establish a future hunting stock.

About 4,000 years ago, the introduction to pigs accelerated, when early agricultural communities transported domestic pigs across Island Southeast Asia. Their roughly 6,600-mile-long journey began in Taiwan, extending across the Philippines, to northern Indonesia (Maluku), into Papua New Guinea, and on to the outlying islands as far away as Vanuatu, and remote Polynesia. The team also found evidence for the introduction of European pigs during the colonial period.

Eventually, many of these domestic pigs escaped and some of them became feral. On the Komodo islands, the domestic pigs hybridized with the warty pigs that were brought over by people from Sulawesi thousands of years earlier. These hybrid pigs are now a major source of food for the islands’ signature species—the endangered Komodo dragon.

“By sequencing the genomes of ancient and more recent populations we’ve been able to link those human-assisted dispersals to specific human populations in both space and time,” said Larson.

Conservation conundrums

According to the team, this study shows the dramatic and enduring impact of human activity on local ecosystems in the Pacific, and raises some conservation conundrums. The region’s pigs have very different statues and impacts across the islands today. Some are considered spiritual beings, while others are viewed as pests, and some are so ingrained in local ecosystems that they could almost be considered native. Efficient conservation policies will need to navigate these complexities.

“It is very exciting that we can use ancient DNA from pigs to peel back layers of human activity across this megabiodiverse region,” said study co-author and paleogenomicist Laurent Frantz. “The big question now is, at what point do we consider something native? What if people introduced species tens of thousands of years ago, are these worth conservation efforts?”