Anesthesia is an integral and vital part of most surgeries. But the amount of anesthesia that doctors give their patients is still based mostly on a patient’s weight and how they respond to the medicine. As patients go under anesthesia during surgery, doctors usually decide whether or not to give more anesthetic based on a rather arbitrary method: If the patient is still awake, give them more of the drug until they fall asleep. While this can work, anesthesia can also be risky, especially for people with heart conditions, and it’s hard to predict how someone will respond to the anesthesia until they are actually given it. But a team of researchers at the University of Cambridge thinks EEGs, machines that can monitor your brain waves, can help anesthesiologists better monitor how awake their patients are so they can more precisely give the right amount of the drug. Their work was published today in the journal, PLOS Computational Biology.

When a person is awake and alert, the brain sends electrical signals back and forth to neurons in different areas of the brain, which helps that person think, move, and communicate. An EEG captures those signals and can give doctors an idea of just how conscious a person is. As the researchers note, there have been many advances in recent years that show how brain networks generate consciousness, however that general idea has been hard to apply to individual patients undergoing anesthesia, since responses to these drugs vary significantly from person to person.

The researchers wanted to better understand why that variation exists, and if they could better predict how an individual patient will react to a particular anesthetic. Giving exactly the right dose of anesthesia is very important, as too much could cause an increase in side effects (both during and after surgery), and too little could make the person remain conscious or wake up during the surgery itself.

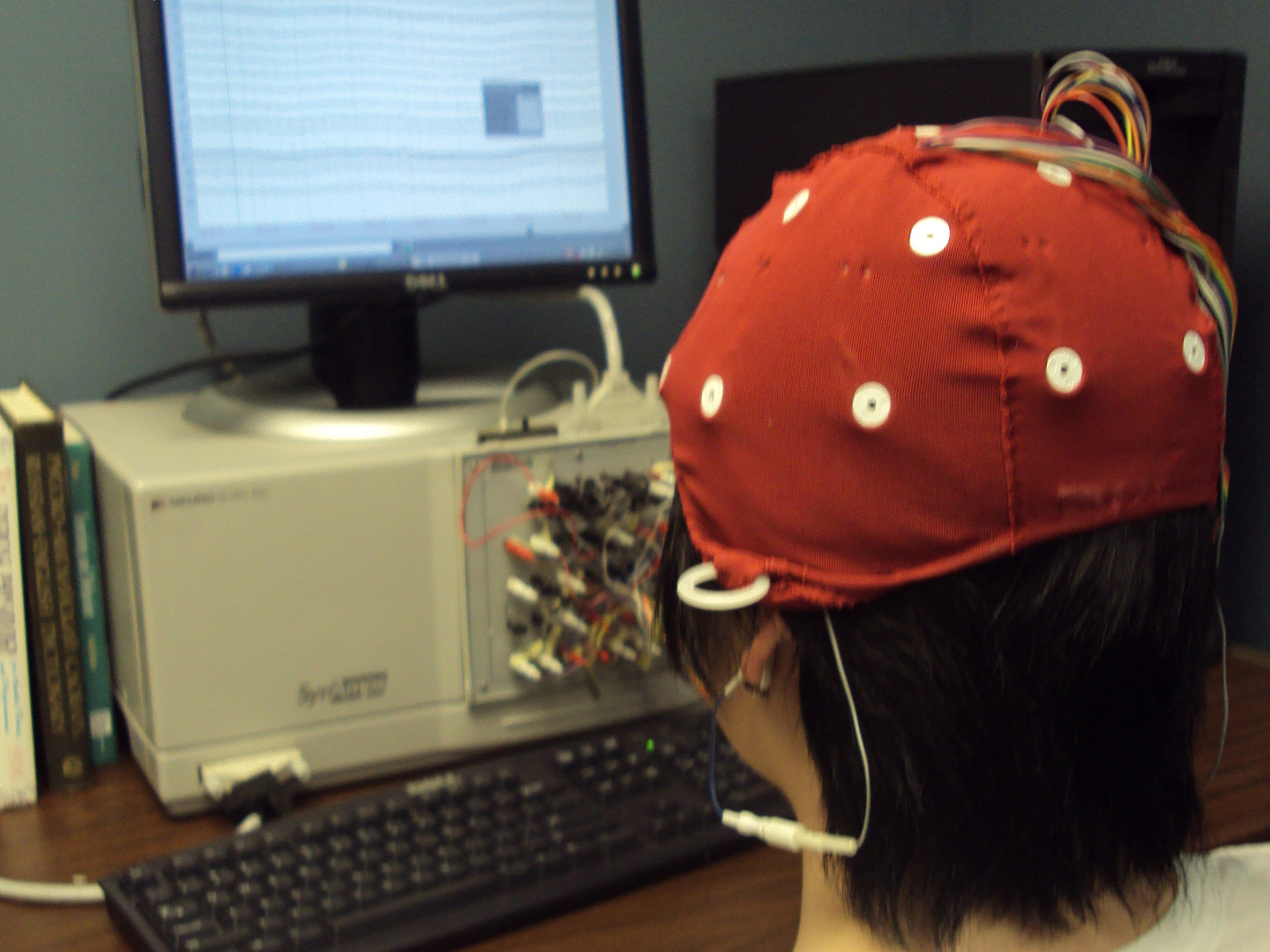

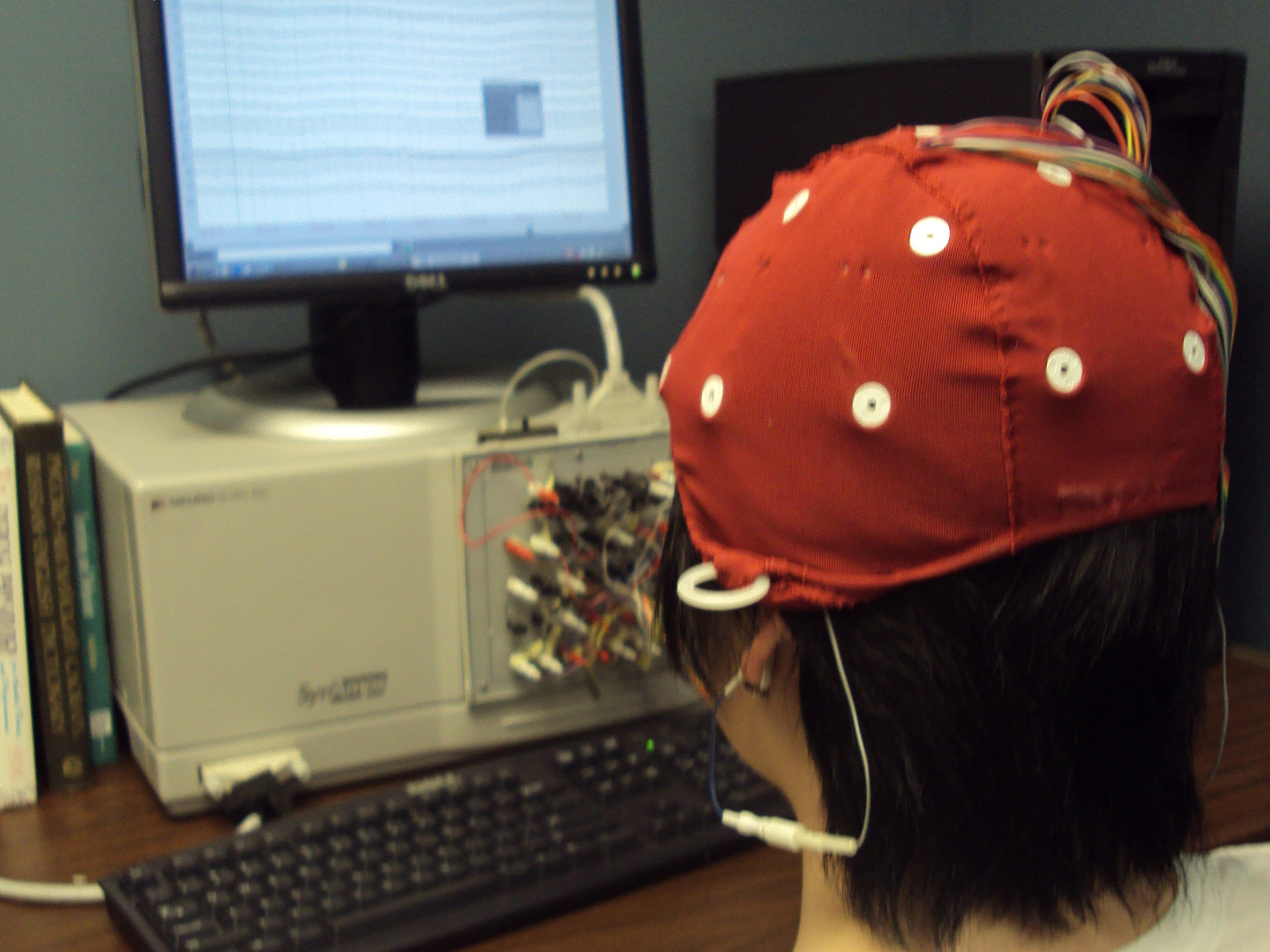

Knowing this, the researchers wanted to see what the EEG of a person undergoing anesthesia looked like and whether it could help them decide how much of the drug to give. To figure that out, the researchers hooked up 20 people to an EEG and gave them all the same steady dose of a common anesthetic called propofol. As the drug infused, the participants were told to press a particular button on a controller if they heard a “ping” noise and another button if they heard a “pong.” The EEG measured each person’s brain activity as they performed the task and received the drug. The researchers also measured the amount of the drug in the patients’ blood.

After the participants received the entire dose of propofol, the researchers found that some were still awake while others were completely unconscious. By comparing the EEGs with the level of consciousness and the amount of propofol measured in the patients’ blood, the researchers found that those who had less brain activity just before receiving the propofol, were more likely to be unconscious after receiving the full dose than those who had more brain activity at the start—even though all patients showed about the same amount of propofol in their blood. The researchers think that hooking up patients to an EEG before and during surgery could show their level of brain activity at the start and more precisely give the correct amount of the drug.

“A very good way of predicting how an individual responds to our anesthetic was the state of their brain network activity at the start of the procedure,” Srivas Chennu, the lead researcher of the study, said in a press release. “The greater the network activity at the start, the more anesthetic they are likely to need to put them under.”

The researchers point out that EEGs are highly available in hospitals and are relatively cheap. In the future the researchers hope to do further tests that would help optimize how EEGs can most benefit patients and anesthesiologists before and during surgery.