Glaucoma is a leading cause of blindness, affecting some 60 million people worldwide. It’s also highly treatable, if caught early. The disease typically occurs when fluid pressure inside the eye rises, choking the optic nerve and causing irreparable damage. To detect this often sudden shift, a team of doctors at the University of Washington is developing a wireless sensor small enough that it can be attached to a lens and implanted in the eye. It will send data to clinicians in real time through a peripheral device. (Currently, doctors screen at-risk patients every three to four months.) The system may be ready for human trials in as few as five years.

How It Works

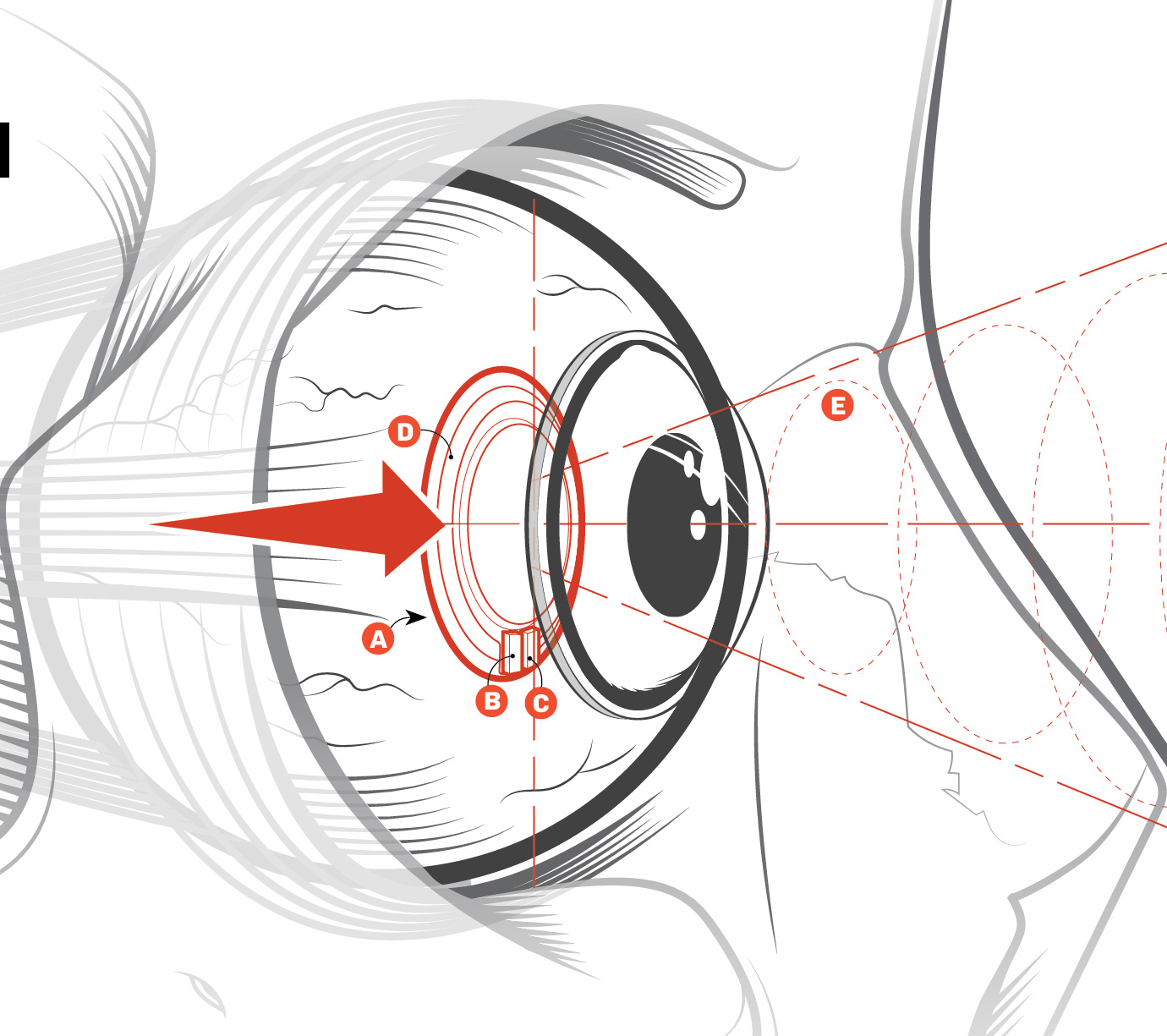

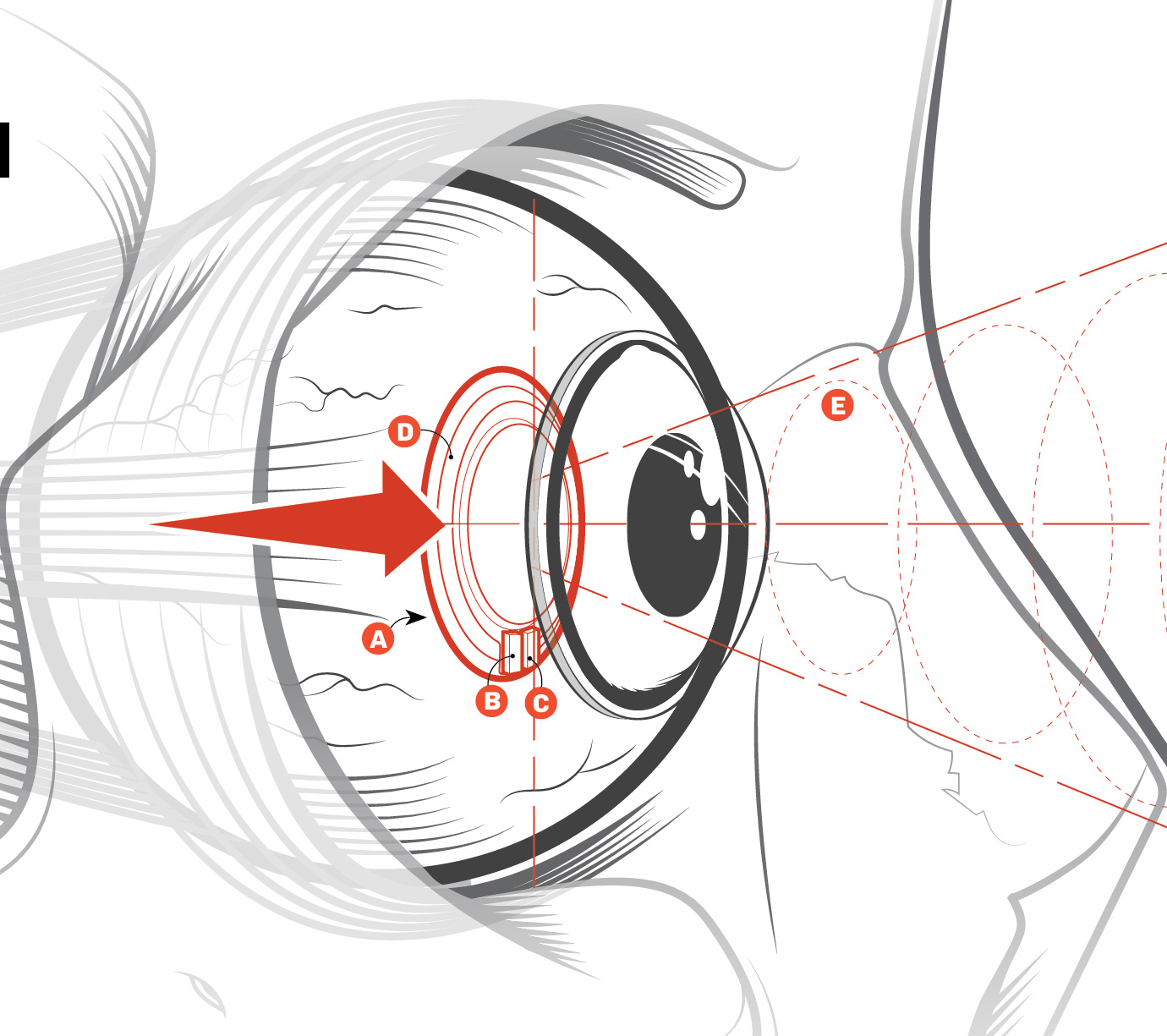

A. A silicone replacement lens, similar to the ones used in cataract surgery, contains the device’s electronics.

B. A sensor on a printed circuit board (PCB) continually monitors fluid pressure inside the eye.

C. A microchip, also located on the PCB, converts pressure data into a radio-frequency signal.

D. A stabilizing tension ring encircling the device holds the antenna, which acts as both a power receiver and a data transmitter via radio waves.

E. Data is sent to an external receiver, which will be a dedicated device or a phone peripheral. A doctor will interpret the data and look for pressure spikes.

Seeing Into the Future

| Augmented Reality Eyewear | A Lens to Monitor Diabetes |

|---|---|

| Innovega iOptik | GoogleX and Alcon Smart Lens |

| “Anything that produces a display—a phone, a computer, a game driver—can produce that same display in our eyewear,” says Jerome Legerton, co-founder of Innovega. The contact lens lets the wearer see within the normal field of vision as well as the up-close media in the glasses. The 60-degree view can even feature 3-D content. Unlike existing video eyewear, iOptik is visible in both eyes; it appears along the top of one’s vision, less obtrusively than a baseball cap. It’s slated for clinical trials in early 2015. | The Smart Lens has a glucose sensor that will measure sugar levels in a person’s tears and wirelessly transfer the data to a smartphone, helping some of the 21 million Americans with diabetes better manage the disease. Eventually, it could even provide immediate feedback on the effects of food and exercise. Franck Leveiller, a vice president of R&D at Alcon, says the lens could be on the market in less than a decade. “It’s a platform,” he says, “so we see it as something that can go far beyond glucose-sensing.” |

This article was originally published in the January 2015 issue of Popular Science.