The Guggenheim Bilbao museum in Spain is the largest titanium-clad building in the world, with 344,000 square feet of 16-thousandths-of-an-inch-thick pure titanium, designed by Frank Gehry. It’s quite a pile, and I understand they also have art or something inside. To learn more about working with titanium sheeting, I set out to build a modern architectural wonder of my own: the Guggenheim East-Central Illinois Birdhouse.

- Dept: Gray Matter

- Element: titanium

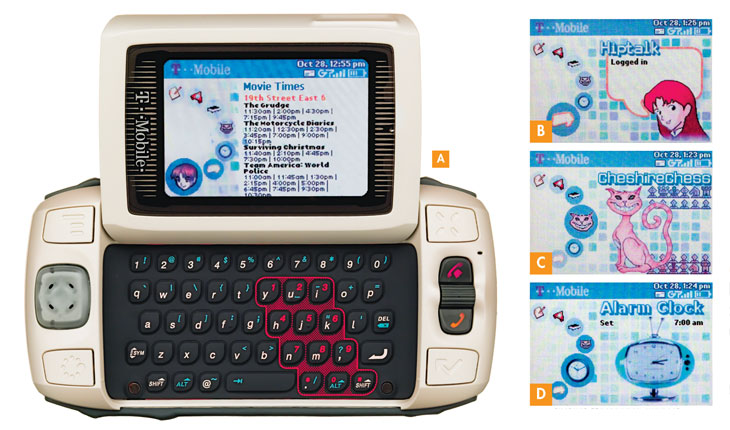

- Project: anodizing a titanium birdhouse

- Cost: $75

- Time: 2 hours

- Difficulty: dabbler | | | | | master (Editor’s note: 1/5)

Titanium justifies its high cost (I paid $33 a square foot at titanium.com) by its great strength, its weather resistance, and its lovely colorful oxide layers. A transparent coating of oxide just a few wavelengths of light thick creates color on the surface through wave interference created when light reflected off the coating meets light reflected off the metal surface underneath.

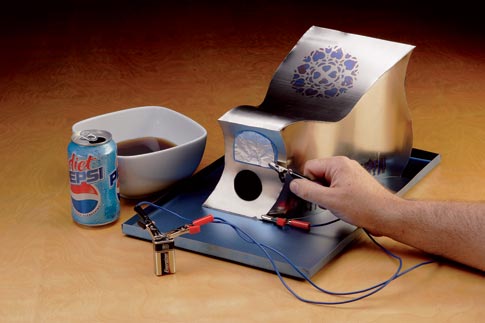

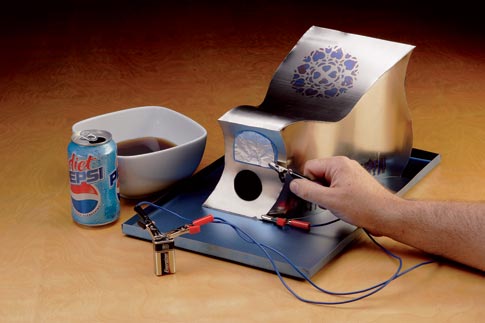

Iron spontaneously forms an oxide layer—what we call rust—but it’s not transparent. Aluminum forms a transparent layer, but it’s too thick to make colors. Titanium is too chemically stable to form a coating spontaneously, which is partly why it’s such a good metal for buildings, but you can force the coating artificially using 9-volt batteries, a paper towel, and a solution containing phosphoric acid (I prefer Diet Pepsi, but any cola will do).

The idea is to run current through the soda and into the metal surface. Attach the batteries, then dip the titanium in a tub of cola to cover the whole surface, or use a pad or brush soaked in the soda of your choice and clipped to a battery to “paint” or form patterns. You can even use tinfoil to distribute current through a paper towel placed over a stencil.

As current flows to the metal, an insulating layer of oxide builds up, stopping when it is just thick enough to block the applied voltage. The thickness of the resulting layer is extremely consistent, within a small fraction of a wavelength of light. Higher voltage forces it to grow a thicker coating and thus creates a different color. One 9-volt battery gives a pale yellow, two gives light blue, three gets you to a deep blue. As you add more batteries, the colors cycle: A coating 3.5 wavelengths thick gives the same color as one 2.5 wavelengths thick, and so on. (Just be careful, because enough batteries combined can eventually produce voltages capable of delivering a painful or even deadly shock if you touched the wet towel.)

These colors are absolutely permanent. They are impervious to sunlight, acid rain, bird droppings, you name it. I wonder if the guards around the Guggenheim have instructions to keep a lookout for suspicious people carrying batteries and refreshing drinks. The possibilities for electro-graffiti on a titanium building that size are mind-expanding.

This story has been updated. It was originally featured in the August 2005 issue of Popular Science magazine.