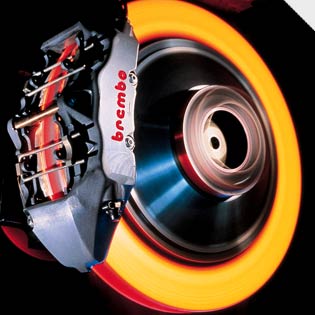

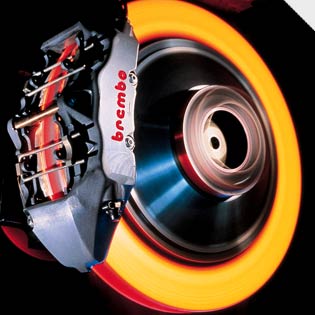

A set of top-end brakes can cost half the price of a new engine. Courtesy Brembo

Posted on Apr 26, 2003 12:21 AM EDT

I’m about to do a brake job on my daughter’s fun-racer, the 1983 911SC Porsche coupe that I spent two years turning from somebody’s sorry beater into her loud, slick, tautly sprung street-and-track machine.

This brake job is costing me $4,800 just for the parts. (My labor is free, which is about what it’s worth.) No, that’s not $4,800 for brake pads and turned rotors–your standard “brake job.” Even Porsche parts aren’t that overpriced. What I have waiting in my little cellar workshop is an entire new brake system: huge front and rear four-piston Brembo calipers, massive cross-drilled and vented rotors, a Turbo Porsche master cylinder, vacuum booster, brake lines, high-temp brake fluid…most of it originally designed for the 1,100-horsepower Porsche 917 Le Mans and Can-Am car.

The calipers and rotors were modified for mounting on an SC by my Porsche guru Steve Weiner, of Rennsport Systems in Portland, Oregon. The 1989 Turbo rotors that he rehabilitated were originally cast by Porsche with the myriad holes for gas venting and rapid water dissipation that also look so cool. (Here’s how cool: I remember asking a Ferrari PR guy why the full-race 360 Modenas at a Ferrari Challenge race had channeled but solid rotors while the ordinary road 360s’ rotors were cross-drilled. “Cosmetics,” he said.)

Porsche measures and boasts about braking power by relating it to the horsepower of its cars. In the basic 911, for example, is “a braking system that is approximately four times as powerful as the engine.” The set I’m installing can do almost 1,500 hp worth of work, in a car that probably weighs about 2,500 pounds and whose engine on a good day might motor along at about 270 hp. Newer Porsche Turbo Brembos, 30 percent more capable than my set, are sometimes referred to as 2,000-hp “hand-of-God brakes,” and can do His deceleration work all day long.

The technical problem of mechanically assisting the deceleration of a machine obviously dates back at least to the invention of the wheel. Some of the earliest brakes were blocks of wood or metal that bore against a wheel rim and rubbed hard enough to gradually slow it. Not a lot of progress was made in said technology for a long time. I’ve seen some pretty primitive brakes, for example, on flying machines. I flew a Russian Antonov An-2 cargo biplane that was about the size and speed of a Winnebago. It had pneumatic brakes, activated by sausage-shaped bladders that inflated to press brake shoes against the inside of a brake drum. They wheezed and farted and eventually locked solid as I was taxiing back to the ramp. RAF Spitfires, believe it or not, had a similar system.

Indeed, the invention of disc brakes was sparked by aviation requirements: the need to stop heavy, fast-moving early jets by the application of braking power to just the main wheels. Airplane brakes face brief but stringent demands, and they can be a factor in a machine’s overall performance. When I flew a Cessna Citation 500–an economy business jet slow enough we joked that we would be rear-ended in flight by Learjets–we were not allowed to take off for 30 minutes after landing on a runway that required major braking effort. Otherwise, if we had to reject the next takeoff, the brakes would be so hot the tires would catch fire.

Jaguar brought disc brakes to racing in the early 1950s, on the Le Mans C- and D-Types, at a time when even the Mercedes juggernaut was still relying on huge, finned, inboard drums. (The patent for automotive disc brakes was held by British Dunlop, which wouldn’t sell the brakes to the Germans.) The Jags were slower than the big Ferraris and Benzes, but they’d drive deep past the Italians and Germans at every corner before they had to brake, and be long gone by the time the competition had managed to slow and go again.

And that’s the key to the other way in which good brakes relate to horsepower: If a 270-hp racecar is going into a corner alongside a lesser-braked 370-hp machine, it can go deeper into the corner before braking and then start its acceleration out the other side sooner. On the right racecourse, that can negate the engine-power advantage. Out-braking a competitor becomes more meaningful than his ability to out-accelerate you. In other words, stop can be more important than go.

If you ask your average enthusiast driver which is the trickiest pedal to use, he’ll probably answer “the clutch.” This is wrong. Few of us, and I don’t count myself among these select few, have the experience and talent to brake correctly. In a panic situation, we either brake too gently or, if the accident is truly imminent, so hard we lock up the wheels. In fact, that’s why the Germans first developed ABS and then added “brake-assist” electronics to apply extra braking when the microchip senses a panic stop that is far too puny.

“You can teach somebody in a day or two how to read a corner, how to go around it, how to pick an apex, but learning to decelerate a car at its maximum is a feel, a matter of experience, and many people never develop that feel,” Weiner says. “It’s the toughest thing to teach a driver.”

Here’s another thing that’s hard to teach: Good brakes are worth the money I’m paying for those Brembos. Weiner notes that “Americans who want high-performance cars have no qualms about spending $10,000 to make a car accelerate faster, but they recoil in horror if you suggest they spend half that amount to stop the car faster. Adding horsepower without paying any attention to the brakes is all part of our culture.”