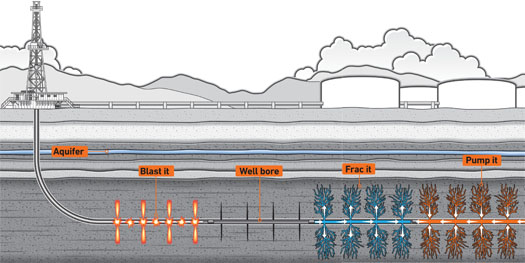

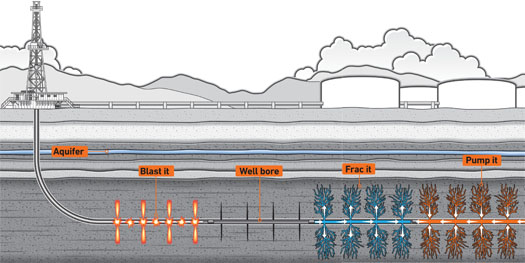

Need some natural gas? To generate more of it—and more income—energy companies are resorting to creative measures, eking out every last bit from the gas wells they drill. But environmentalists and public-health advocates warn that one such process, called hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, can also taint nearby water supplies. Advances in horizontal drilling technologies have allowed energy producers to reach gas packed in dense rock formations that happen to coexist with the sources of drinking water for a sizeable segment of the U.S. population. This fall, the Environmental Protection Agency is releasing a plan to study the health hazards of the practice.

How to Wring Gas from a Stone

1. BLAST IT

Once a well is drilled and a pipe is secured half a mile or more into the shale, well workers send a “perf” gun down into the pipe. The gun shoots small explosives that perforate the well casing and the rock along the well bore. When the well is complete, the natural gas will flow through these channels.

2. FRAC IT

To make the fracturing fluid, well workers mix sand and a variety of potentially hazardous chemicals, such as benzene, into the water. They send the mixture into the well at a pressure of 10,000 pounds per square inch. The pressure cracks open the rock while the sand grains prop open the tiny fissures.

3. PUMP IT

Well workers stop the pumps. This loss of pressure draws the frac fluid and natural gas, which begins seeping out of the shale and into the bore of the well, up to the surface. In addition to containing natural gas, the frac fluid that emerges from the well is now replete with salt, heavy metals and naturally occurring radioactive materials—all of which pose health and pollution hazards. This spent fluid is stored on-site in pits or storage tanks until it’s hauled away to be pumped into deep injection wells, or to wastewater-treatment plants.

FAQs

WHY FRAC?

It’s cheaper for an energy company to drill one well with multiple horizontal legs and frac the well than it is to drill many vertical wells and build infrastructure for each one. In Pennsylvania, some customers saw the results fracking could have on their utility bills, which dropped from $122 to $102 in one month.

WHAT’S THE DANGER IN FRACKING?

Each step has room for error. Trucks can spill chemicals, wells can blow out belowground, wastewater holding tanks can spring holes. Carcinogenic chemicals, including benzene, may leak from the well into an aquifer. A single well could contain enough benzene to contaminate 100 billion gallons of drinking water, according to drilling-company disclosures in New York State.

WHAT’S IN FRAC FLUID?

Tough to say. Gas drilling is exempt from the Safe Drinking Water Act, and companies are not required by the federal government to disclose the fracking chemicals in each well. Recent legislation in Wyoming now demands that information. We know that frac fluid is approximately 98.5 percent water, 1 percent sand and 0.5 percent other chemicals. According to Pennsylvania’s Department of Energy, these chemicals include potassium hydroxide and propylene glycol.

CAN IT BE MADE SAFER?

Maybe. Anthony Ingraffea, a civil and environmental engineer at Cornell University who has studied hydraulic fracturing since 1982, says our best bet lies in better ways to recycle the used frac fluid. Since 2009, the U.S. Department of Energy has awarded groups funds to research new techniques to treat this waste.

Essential Jargon

TCF: Units of a trillion cubic feet are used to measure resources in the ground, or annual national energy consumption. One tcf is enough natural gas to heat 15 million homes for one year, generate 100 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity, or fuel 12 million natural-gas-fired vehicles for one year.