To keep a handful of rat livers super-fresh, researchers kept them supercool—that is, stored at temperatures below the freezing point of water.

The procedure was part of an experimental new method for treating donated organs. The method is still in its early stages of development, but it’s showing some promise. Rat livers treated in this new way lasted three times as long in storage as rat livers treated in the way that’s currently the gold standard for human transplants, which involves a special liquid bath and cooling to cold but not supercold temperatures. Before even thinking about testing the method in humans, researchers will have to see if it works in lab animals that are larger than rats—bigger livers are harder to cool safely.

The research is part of an ongoing effort to extend the time doctors are able to store donated organs. Longer storage times means more wiggle room for doctors. Say someone who lives in Asia needs a liver transplant. If storage times were long enough, the Asian patient could get a North American liver, should no compatible livers be available closer by. Right now, doctors are able to store donated livers for up to 12 hours before they really need to transplant them into a person.

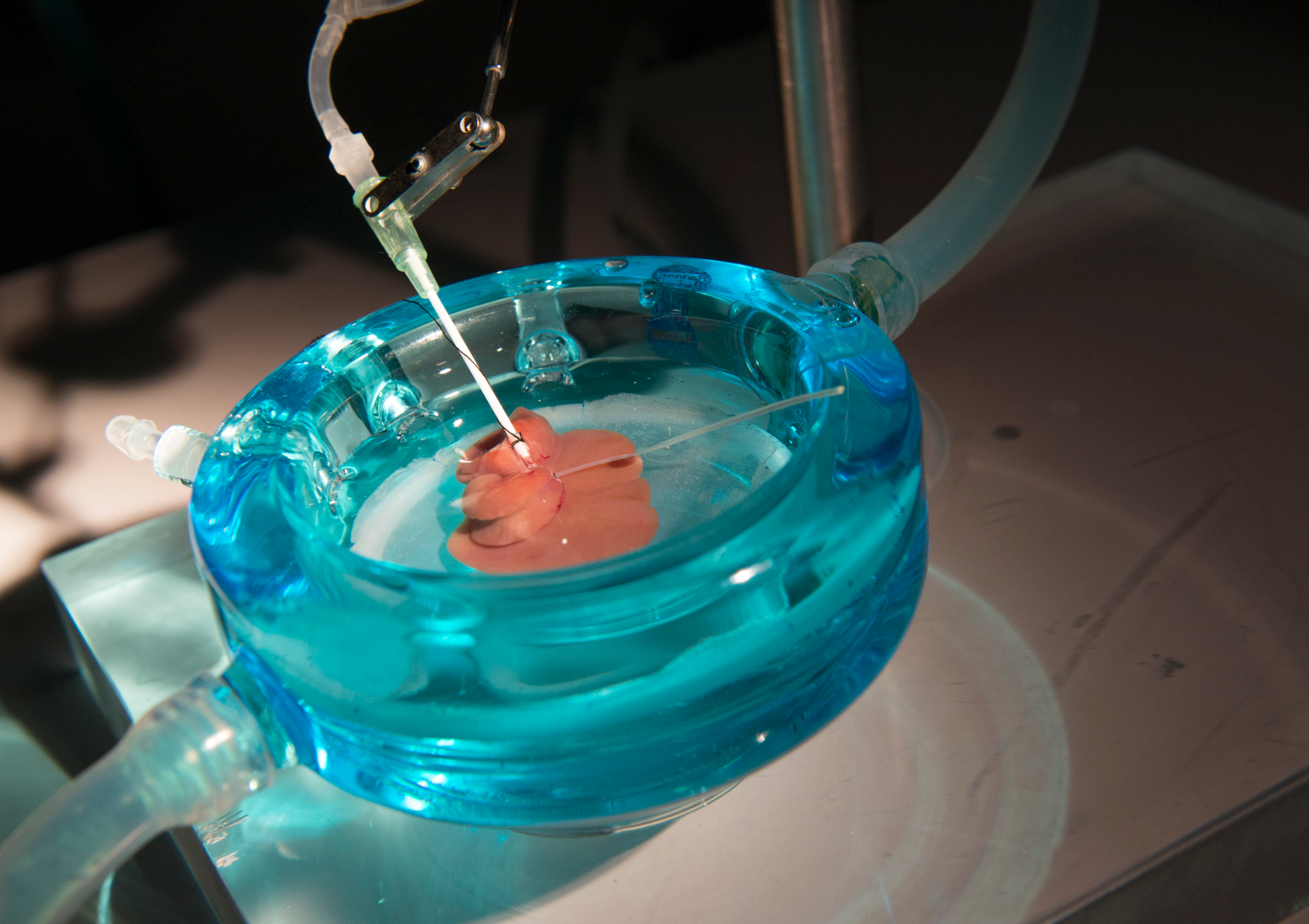

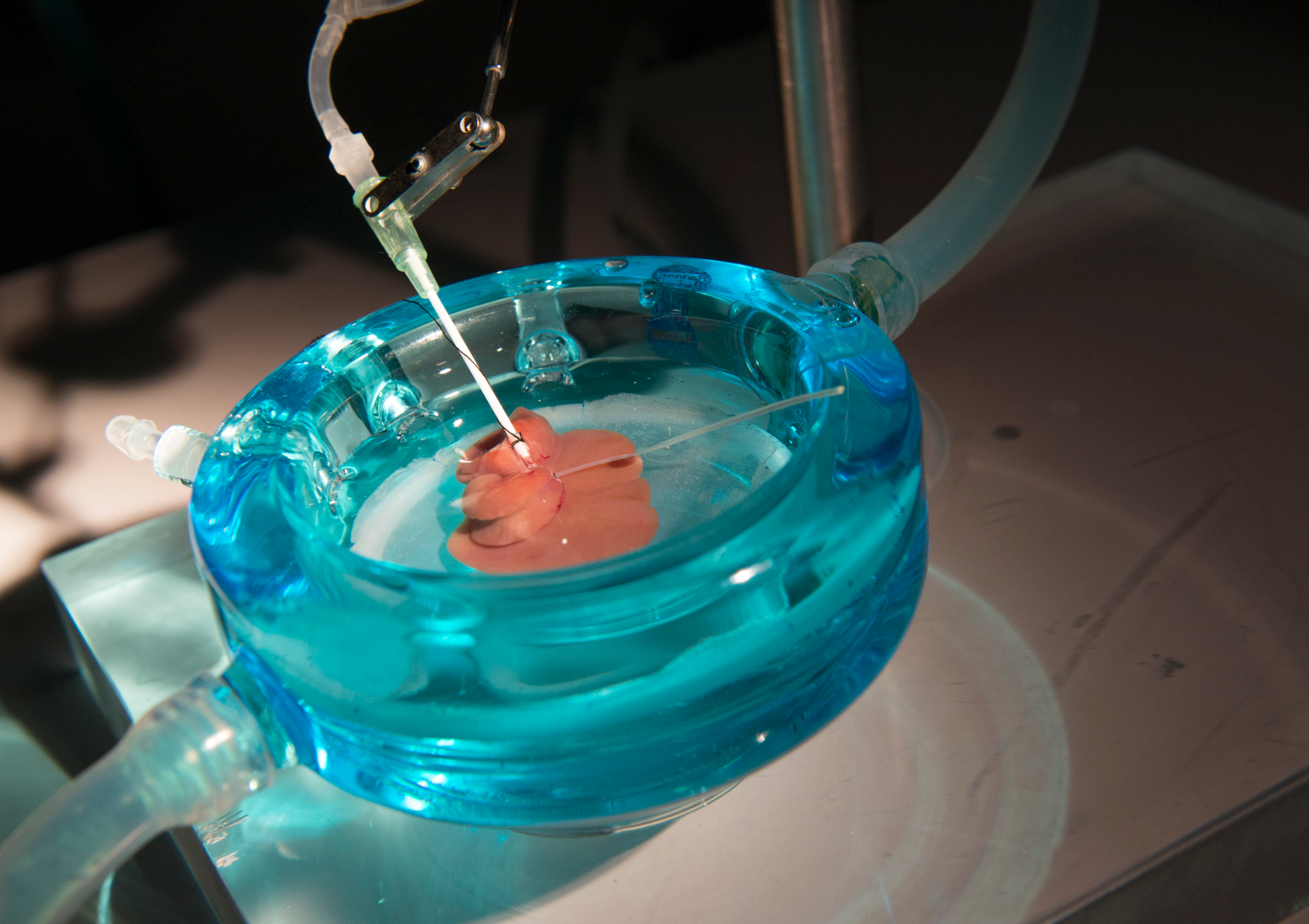

The researchers bathed their rat livers in a liquid containing two non-toxic anti-freeze molecules.

Of course, keeping things extra-cool is an obvious way to store living tissues for longer. That’s the whole idea behind cryopreservation, right? At temperatures below freezing, however, there’s always the danger that water in the tissues will form ice, which is damaging. The cooling-and-rewarming process can also irreversibly damage cells in biological tissue. So, for the new method, a team of researchers from the U.S. and the Netherlands bathed their rat livers in a liquid containing two non-toxic anti-freeze molecules. They also used a special machine that helped circulate the liquid through the livers before cooling them and before transplanting them. The circulating anti-freeze kept the livers safe even as they were brought down to -6 degrees Celsius.

The researchers found that they were able to store their rat livers for three days, then transplant them into healthy rats. All six rats who received those three-day-old livers survived the entire duration of the study, which lasted three months. An additional 12 rats received supercooled livers that had been stored for four days. Seven of those little guys survived for three months. On the other hand, all of the rats died whose liver transplants had been treated in the usual way, but stored for three days—much longer than the 24 hours that researchers have previously found is tops for rat liver transplants.

The American-Dutch team published its work online yesterday in the journal Nature Medicine.