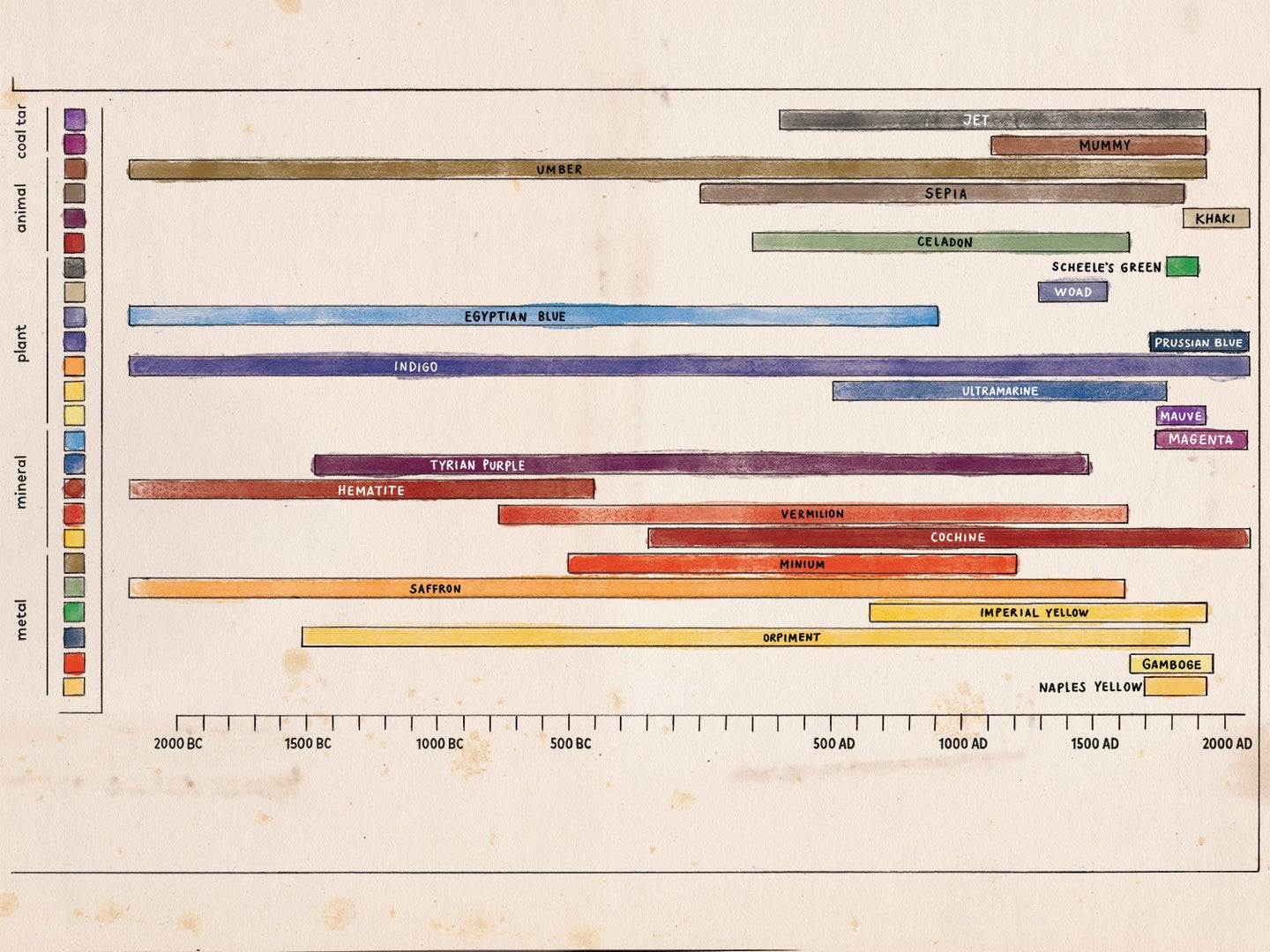

How humans created color for thousands of years

Back before we could paint our world with pixels, we needed precious commodities to make pigments.

Most of the hues we look at these days come courtesy of 16,777,216 alphanumeric keys called Hex codes; tinting your technicolor digital life is as simple as copying a string of characters. But the shades on this page—and all your off-screen belongings—come from resources we must conscript to create our chosen chroma. Affixing color to an object (and making it stick) is tricky business. For most of human history, we’ve derived dyes from nature: People cooked plants and animals until they produced the desired pigment, or mined precious minerals from subterranean seams and ground them into paints. But even once we took to the lab to concoct new colors, some shades remained rarefied. This chart shows a few of the commodities that tint our kaleidoscopic world—and how long it took their popularity to fade.

1. Tyrian purple

Phoenician and Roman emperors loved that this wine-colored dye didn’t fade. But making just an ounce meant milking or crushing 250,000 Murex sea snails, which use their tinted mucus to protect eggs and sedate prey.

2. Ultramarine

For more than a thousand years, a single region in Afghanistan was the only source of lapis lazuli, the blue rock we refine into ultramarine. Scarcity and a supposed resistance to fading made it as valuable as gold for millennia.

3. Imperial yellow

Only the Chinese emperor and his representatives were allowed this spiritually significant shade. With a simple wood-ash mordant—an oxide that affixes dyes to materials—the golden foxglove-plant extract easily sticks to silk.

4. Mummy

“Dead man’s head” was one part oil, one part amber resin, and too many parts Homo sapiens. It got its brown tint from the flesh, bones, and bandages of well-preserved Egyptian corpses. Fittingly, artists used it for skin tones.

5. Scheele’s green

While Carl Wilhelm Scheele worried his lab-derived copper arsenite tincture might be toxic, it was also bright and stable. Companies used it on everything from wallpaper to dresses—until (and, in some cases, after) people started dying.

6. Perkin’s mauve

Chemist William Perkin accidentally invented his eponymous purple while trying to synthesize the malaria treatment quinine from coal tar in 1856. Victorians adored it, but what we call “mauve” today is a more demure shade.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2019 Make It Last issue of Popular Science.