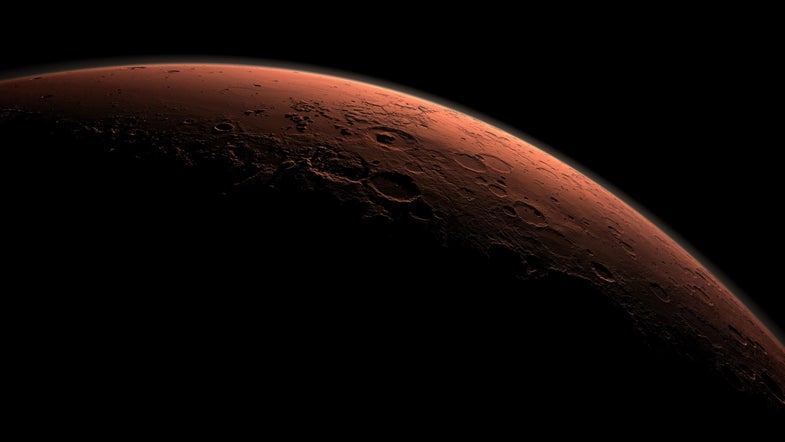

How You’ll Die On Mars

Many hopefuls have signed up for a one-way ticket to the red planet. But if they aren't prepared, the trip may be a short one.

We’re on our way to Mars. NASA has a plan to land astronauts on its surface by the 2030s. Private spaceflight companies like SpaceX have also expressed interest in starting their own colonies there, while the infamous Mars One project has already enlisted civilians for a one-way trip to our planetary neighbor in 2020.

While many may dream of living their remaining days on Mars, those days may be numbered. The Martian environment poses significant challenges to Earth life, and establishing a Mars habitat will require an extraordinary amount of engineering prowess and technological knowhow to ensure the safety of its residents.

The technology required to keep astronauts alive on Mars isn’t ready–and it may not be for many years.

Though we may soon have the launch vehicles needed to transport people to Mars, a lot of the technology required to keep astronauts alive on the planet just isn’t ready–and it may not be for many years. For those eager to get to Mars as soon as possible, take caution: A number of tragic outcomes await if you head that way too soon.

You’ll Crash

Let’s say you’ve spent many months on your deep space voyage, and you’ve finally made it into orbit around the red planet. Congratulations! Now you need to get down to the surface—and that’s going to be tricky.

The problem is Mars’ atmosphere. The air around Mars is quite thin–about 100 times less dense than the atmosphere around Earth. Spacecraft returning to our planet rely on a combination of parachutes and drag from the atmosphere to slow them down. The heavier the object, the more drag it needs to prevent it from slamming into the surface.

But with so little atmosphere surrounding Mars, gently landing a large amount of weight on the planet will be tough. Heavy objects will pick up too much speed during the descent, making for one deep impact.

Low-Density Supersonic Decelerator

“How we get down through the atmosphere to the surface is a critical challenge,” Bret Drake, deputy manager of the exploration missions planning office at NASA, tells Popular Science. “With current landing techniques, we can land only a metric ton on Mars. That’s not big enough to get a colony going; we’ll need much bigger capabilities.”

According to Drake, NASA will need to land between 20 to 30 metric tons in one trip to get all of the astronauts and supplies needed for a planetary habitat down to the surface safely. To do this, the space agency is coming up with unique lander designs—notably their inflatable Low-Density Supersonic Decelerator. Shaped like an iconic flying saucer, the LDSD’s disc shape and added inflatable balloon increase the surface area of the lander, allowing it to slow down in thinner atmospheres.

The LDSD is still undergoing tests here on planet Earth, with an upcoming test in Hawaii scheduled for June. Whether the lander will be able to land such a heavy payload on Mars’ surface has yet to be determined.

As for Mars One and SpaceX, no specific information has been given about how they plan to land on Mars just yet.

You’ll Freeze

Welcome to Mars! (That’s assuming you’ve made it down in one piece.) It’s time to get acquainted with your new home’s weather conditions.

Mars temperatures average around -81 degrees Fahrenheit, but swing wildly depending on the season, the time of day, and the location, ranging from 86 degrees Fahrenheit near the equator to -284 degrees Fahrenheit near the poles. That means astronauts will have to be equipped to battle harsh, bitter cold.

Mars Polar Ice Caps

NASA has learned a lot about sheltering astronauts from fluctuating temperatures, thanks to years of housing humans on the International Space Station. When exposed to the sun, the ISS endures heats exceeding 200 degrees, and then plunges into -200-degree temperatures on Earth’s night side. The ISS and astronauts’ space suits use specialized thermal control systems and processes like sublimation to both repel excess heat and to shield people from the cold.

Yet those control systems are designed to work well in vacuum. Entirely new methods will be needed for space suits and habitats in the atmosphere of Mars. Though it’s thin, it still contains gases which can convect heat to and from a suit (similar to how wind cools us down here on Earth). So astronauts will feel the rapid temperature changes much more harshly.

“We would need a solution that provides better insulation for the cold environments and a different way of rejecting heat for the hot environments,” says Drake. “A spacesuit in a vacuum is very similar to a thermos, but a space suit on Mars is much more like a coffee cup sitting on a kitchen counter – the coffee cools much faster in the plain cup on the counter top as compared to the coffee in the thermos.”

You’ll Starve

Mars Farming

Living in a habitat on the Martian surface will be somewhat similar to living in the remote research outposts of Antarctica. All the food and supplies needed for these stations must come from other continents, and cargo resupply missions aren’t frequent.

Mars is just a bit further away from mainstream civilization than Antarctica is, and any resupply missions to a Martian habitat would take months or years to complete. If any colony hopes to survive on the red planet, there must be some form of self-sustainability when it comes to food. That means you’ll need some interplanetary farming skills.

Mars One’s plan is to grow crops indoors under artificial lighting. According to the project’s website, 80 square meters of space will be dedicated to plant growth within the habitat; the vegetation will be sustained using suspected water in Mars’ soil, as well as carbon dioxide produced by the initial four-member crew.

“The amount of crops you could sustain just by using the CO2 produced by people is only sufficient to feed half of the crew.”

However, analysis conducted by MIT researchers last year shows that those numbers just don’t add up.

“When you’re growing all the crops required to feed four people indefinitely, the carbon dioxide produced by the crew is insufficient to keep the crops alive,” says Sydney Do, an aerospace engineer at MIT and lead author of the report. “So essentially the crops die off very quickly, within 12 to 18 days.” Adding more people wouldn’t solve the issue, because then there wouldn’t be enough to eat. “The amount of crops you could sustain just by using the CO2 produced by people is only sufficient to feed half of the crew’s dietary requirements,” said Do. Talk about a catch-22.

So what can be done to fix this problem? You can grow fewer crops, but that means the astronauts will eventually run out of an important food source. Or you can find a way of introducing extra carbon dioxide, perhaps through CO2 scrubbing technology. Such innovation, which would involve absorbing gas from the thin Martian atmosphere, is only in its infancy here on Earth. But if such tech can be developed for a Martian habitat, using it to grow an increased supply of crops may have some consequences when it comes to the crew’s oxygen supply.

You’ll Suffocate (Or Maybe Explode)

Growing crops on Mars isn’t just for feeding hungry astronauts; plants will serve as a vital source of renewable oxygen for the habitat. It’s a much better option than consistently sending heavy oxygen tanks to the red planet, which will take up too much precious space on resupply missions and cost a lot of money to transport.

Studies have shown plants may be able to grow in Martian soil, however crops have never been grown in the Mars gravity environment, so further testing is required to see if vegetation can survive at all. But if that works, the plants required to feed a multi-person crew will be producing a lot of oxygen. And that’s not necessarily a good thing.

According to Do’s report, too much oxygen in a closed environment can lead to an increased risk of oxygen toxicity for the crew, and even worse, spontaneous explosions. So O2 will have to be vented from the habitat. To do this, the astronauts would need a specialized method for separating oxygen from the gas stream. There are a number of methods for doing so here on Earth (cryogenic distillation and pressure swing adsorption) but none of these technologies have been tested for a Martian environment, and considerable research and development would be needed to make these techniques viable on another planet.

“Significant technology development is required, because the tech isn’t there right now,” says Do. “The technologies needed for this habitat can work here on Earth, but they need a lot of human tending and are very large. In terms of practical use in a space envrionment, it would require miniaturizing them, decreasing cost, and increasing their reliability.”

Recently NASA proposed “ecopoiesis” on Mars –- creating a functioning ecosystem that can support life. Their idea is to send select Earth organisms–like certain cyanobacteria–to Mars, which can then feed on the planet’s rocky terrain to produce oxygen. “Ultimately, biodomes on Mars that enclose ecopoiesis-provided oxygen through bacterial or algae-driven conversion systems might dot the red planet, housing expeditionary teams,” according to a NASA statement. However, the space agency didn’t provide word on how much carbon dioxide the organisms would need, and whether or not they could be sustained by air produced by crew members.

And then there’s MOXIE–the Mars Oxygen In situ resource utilization Experiment–which could negate the reliance on plant-based oxygen. Developed by MIT researchers, this machine works by taking carbon dioxide from the Mars atmosphere and splitting it into oxygen and carbon monoxide. A low-scale version of MOXIE will make its way to Mars on NASA’s next rover, planned for a 2020 launch. If it works, MOXIE could provide a renewable source of oxygen without the conundrum posed by growing crops.

Mars 2020 Rover

You May Not Even Make It There At All

All of these scenarios only become critical issues if you actually make it to Mars in the first place. But the sad truth is you might not even survive the trip. Barring any complications with the spacecraft’s hardware or any unintended run-ins with space debris, there’s still a big killer lurking out in space that can’t be easily avoided: radiation.

Beyond lower Earth orbit, the deep space environment is filled with cosmic rays—highly energized particles. This space radiation easily penetrates the walls of spacecraft, and it’s possible that long-term exposure can have weird effects on human health.

A recent study on mice revealed that long-term exposure to cosmic rays might lead to some abnormal changes in the brain. After subjecting mice to simulated cosmic rays, researchers noticed the mice had lost many important brain synapses. Subsequent behavioral studies on the mice showed they exhibited less curiosity and seemed confused—an eerie result, with upsetting implications for a future trip to Mars.

Beyond lower Earth orbit, the deep space environment is filled with cosmic rays.

But perhaps even more alarming is space radiation’s known ability to increase the likelihood of getting cancer. Currently, NASA monitors every astronaut’s lifetime exposure to space radiation over the course of his or her career. If ever an individual reaches a 3-percent increased risk of fatal cancer from space radiation, NASA grounds the astronaut for good.

On the space station, astronauts are partially protected from cosmic rays thanks to the Earth’s magnetic field, so it takes them some time before they reach that 3 percent limit. But on a years long, deep space voyage, there’s no magnetosphere to keep them safe. Plus some astronauts may be more susceptible to radiation exposure than others.

“Because women in general live longer than men, in the NASA prediction model, they’re much more likely to develop cancer in their lifetime with the same amount of exposure as a male,” says Dorit Donoviel, deputy chief scientist of the National Space Biomedical Research Institute (NSBRI), says. “Calculations have indicated a woman probably should not go to Mars, because the cumulative exposure over the duration of the mission would exceed the maximum allowable 3 percent lifetime cancer risk.”

Mars or Bust?

All of this may seem like a major bummer, but it highlights just how many obstacles we need to overcome before heading to Mars. NASA admits they’re not quite ready either, with the space agency currently soliciting ideas from the general public on how to keep Mars astronauts safe. The contest—dubbed the “Journey to Mars Challenge“—will award $5,000 to three winning participants who come up with ways to develop the elements necessary for sustaining a human presence on the red planet.

“This could include shelter, food, water, breathable air, communication, exercise, social interactions and medicine, but participants are encouraged to consider innovative and creative elements beyond these examples,” NASA said in a statement about the challenge.

Little is known about SpaceX’s plans for a Mars mission, but CEO Elon Musk says he hopes to unveil the details later this year. Yet NASA administrator Charles Bolden has a message for SpaceX, Mars One, and all other private companies with big dreams of visiting the fourth rock from the sun: You’re going to need help. Speaking at a U.S. House Committee Meeting in April focusing on space and technology, Bolden expressed his confidence in NASA’s efforts to get to Mars despite the challenges, though he holds less confidence for all private endeavors. “No commercial company without the support of NASA and government is going to get to Mars.”

The challenges of surviving long-term in a Mars habitat are also explored in The Martian, the debut novel of Andy Weir which will be getting the Hollywood treatment later this year. The book follows astronaut Mark Watney, who struggles to survive alone on Mars after his crew mistakes him for dead and leaves the planet without him. Watney must overcome significant obstacles, such as growing his own food and finding clever ways to procure water. Weir echoes a sentiment shared by NASA: Even if you have all the right technology, you can’t just prepare for a perfectly executed mission. “The main thing you have to do for a Mars trip is account for failures,” he says. “How do you make sure the mission plan accounts for this and that? For the book, I was using my imagination about ‘Hey, what could break?’ But there are several things, several problems we haven’t solved yet.”

Though Weir’s book focuses on the worst-case scenario, he’s confident that we will get to our neighbor someday; it’s just going to take a lot of time and a lot of money. “Getting to Mars is an enormous undertaking that I don’t think we have the technology to do currently,” says Weir. “But we could. It’s going to happen.”