Don’t Inject Yourself With Baby Mouse Blood Cells Just Yet

Young blood may have healing properties, but we don't know why

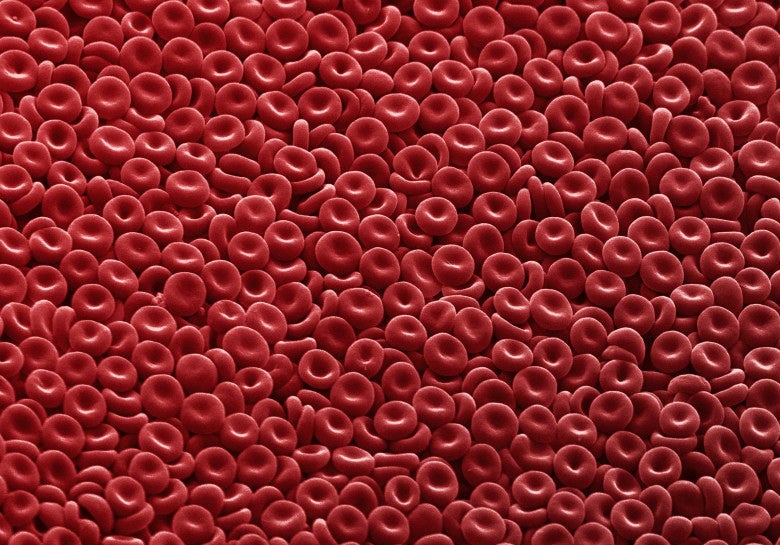

You might be under the impression that young blood is the fountain of youth. A number of studies conducted in older mice (and, once, humans) over the past 10 years have shown benefits from transfusions of young blood, or parabiosis, restoring cognitive function or regenerating muscles. Yesterday, another study was published, in which older mice with broken bones healed faster when injected with young blood. But the mechanism behind these supposed benefits is still being debated, so don’t expect to be able to ask your doctor for a quick transfusion of young blood anytime soon.

In 2013, Amy Wagers, a stem cell expert at Harvard University, thought she had figured out why older mice had healthier hearts after they were injected with young blood. She pinpointed the protein GDF11, found in high concentrations in young blood but gradually lower concentrations as the mice aged. In two subsequent studies, Wagers and her colleagues found that young blood worked other wonders on older mice, boosting the growth of new blood vessels, more neurons in the brain, and better regeneration of injured skeletal muscles. In all of them, the results correlated to changes in levels of GDF11.

But when David Glass, a muscle disease expert at the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, tried to replicate those studies, he found the exact opposite: GDF11 appeared to increase with age, and inhibit muscle regeneration, contradicting Wagers’ findings. For now, both researchers are standing by their findings, as a Nature Communications article notes, which means researchers’ overall understanding for how parabiosis works is cloudy at best.

In this newest study with broken bones, published in Nature Communications, the researchers suggest that a different protein called beta-catenin might be responsible. Older mice have more of the protein; low levels of beta-catenin have been linked to faster fracture repairs, and mutations and overexpression of it lead to various types of cancer. The researchers gave old mice a transfusion of young blood, then monitored how long it took for the old mice to heal fractures in their shin bones as opposed to mice without young blood. Those that had undergone parabiosis healed faster.

These are intriguing results, and the levels of beta-catenin held true to the researchers’ hypothesis, but even the researchers themselves point out that beta-catenin might be one of several proteins that could be at play in the healing process—they really just haven’t been monitoring enough of the protein levels to be able to tell. As other researchers conduct similar studies on beta-catenin and other proteins in young blood, time will tell if the researchers’ conclusion stands.

But in the meantime, it’s too early to start developing quick-healing beta-catenin drugs, or to start these similar trials in humans.