At 10:00 pm on May 5, a team of people quietly approached a leatherback lying in the sand on the Florida beach. Working quickly while the female sea turtle laid her eggs, they drilled two small holes in the back of her shell. Through the holes they threaded zip ties, tying on a small transmitter with epoxy on the back for added security.

Over the next few months, members of the non-profit, Florida Leatherbacks, Inc, watched as Isla the sea turtle visited the beach a few more time to lay new clutches of fragile eggs in the sand, before starting her late summer migration north along the East coast.

“We’re monitoring where she is right now, and it just happens to be in the middle of a hurricane.” Kelly Martin says.

Martin, along with Chris Johnson work for Florida Leatherbacks, Inc, and are currently keeping tabs on Isla.

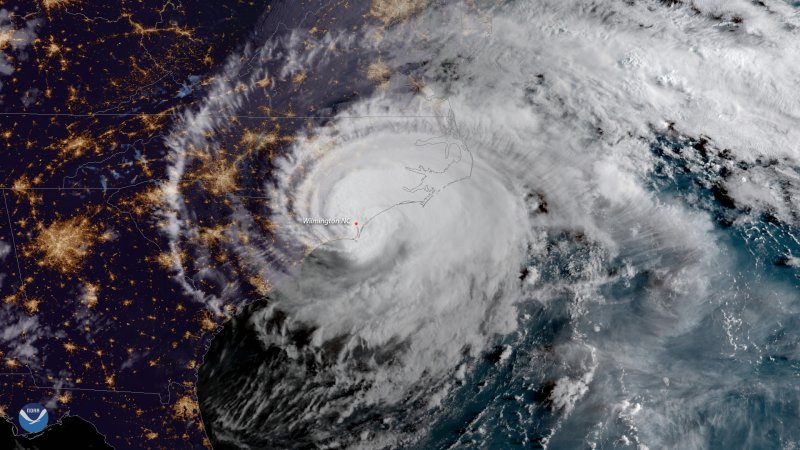

Isla is now off the Outer Banks of North Carolina, to the north of where Hurricane Florence made landfall. For a while it seemed like she would get caught in the massive storm that’s already hitting the coast. She’s north of the worst of it, but is still experiencing rough seas. Even before the hurricane hit, she surfaced in an area where waves reached 14 feet high.

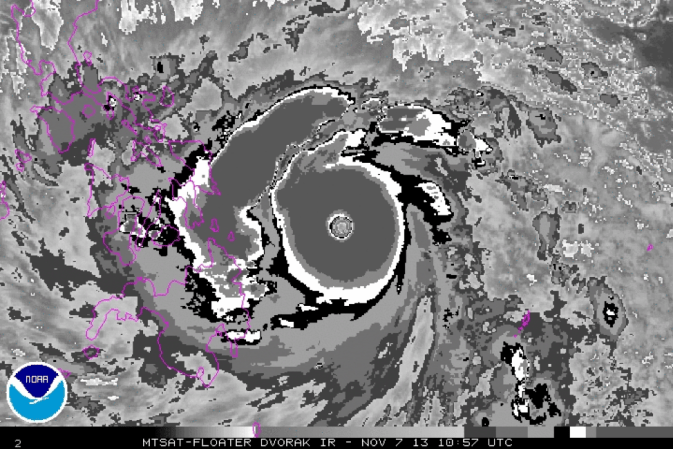

“Turtles are air breathers, so they need to come to the surface periodically to breathe, but I suspect many dive below the surface to weather the storms,” Kate Mansfield, director of the Marine Turtle Research Group at the University of Central Florida says in an email. “I have tracked turtles through some storms in the past and never saw any sort of movement that suggested they were trying to get away from the storm (or that the storms shifted their paths). The turtles I tracked were larger juveniles—at that size they can dive 100s of m deep.”

Mansfield points out that there is some data from a 2006 paper on how Hawksbill turtles behave during a hurricane. While they stayed in roughly the same place, not making any movements to avoid the storm, they became more active, staying beneath the waves for longer periods of time.

Other animals have different coping mechanisms. Nick Whitney is a Senior Scientist at the New England Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life. He studies and tracks sharks, who, especially at a young age tend to react very differently to hurricanes than turtles do.

Young sharks, Whitney says, tend to stay in shallow water, close to shore, where there are fewer predators like large fish or other sharks that might see them as a meal. But when a hurricane approaches, these young sharks head to deeper waters.

“We know they can tell how deep they are.” Whitney says, noting that the drop in atmospheric pressure with an approaching storm might be enough to trigger the behavior. “it may be as simple that it feels like they’re in water that’s way too shallow”

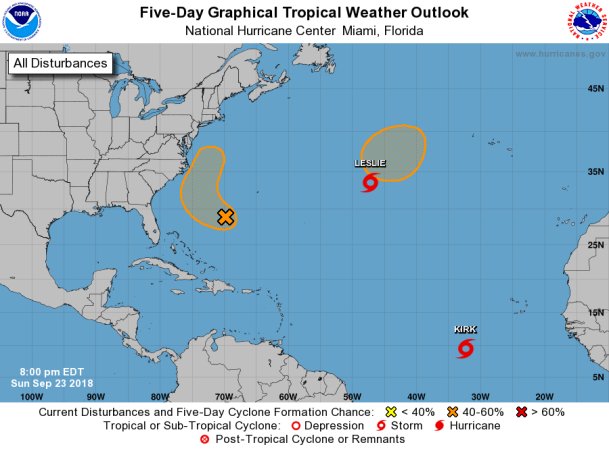

Both turtles and sharks are tracked using satellite tags, but getting a satellite reading in a hurricane isn’t easy. “There are a lot of conditions that have to be just right” Whitney says. In addition to needing relatively low cloud cover for the signal to reach the satellite, the satellite also has to be in the right place, Whitney explains. And that’s not all. “The animal has to break the surface, and the tag has to be dry for at least a few seconds,” Whitney says.

There’s still a lot we don’t know about animals in hurricanes, and it will take more than occasional bits of data to really understand how different species act in the system. Often the data we get on animals in hurricane is gathered by luck, when animals like Isla that have already been tagged cross paths with a storm.

Part of the issue is that in the scale of scientific research, storms happen quickly and are hard to predict, so getting funding for a study can be tricky. And tracking costs money—a lot of money. The transmitter attached to Isla cost thousands of dollars, an expense that the small non-profit was able to afford thanks to partnership with the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

In part because of the expense, Florida Leatherbacks, Inc. is only tracking one animal this season—Isla. They’re thrilled to have the chance to see how Isla (and by extension other leatherbacks) might behave in a hurricane. In the end, to the people participating, the reseach is more than worth the cost. When asked why he studies leatherbacks, Johnson is effusive.

“They’re big rubbery dinosaurs and they nest on the beaches that we live on,” Johnson says. “They’re just the coolest animals”

You can follow along with Isla’s progress on Twitter .