We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

A new grain-of-sand-sized lens could one day compete with those enormous DSLR lenses to create sharp pictures.

A group of scientists at Harvard University debuted their new “metalens” in Science last week, and hope it will have applications in all sorts of imaging, from photography to other optics like microscopes and telescopes. These lenses aren’t just smaller, measuring in at just 2 millimeters in diameter, but potentially much cheaper than the lenses the industry uses today.

“We wanted to replace bulky optics,” Mohammadreza Khorasaninejad, first author on the study, told Popular Science. “We can reduce the cost to 2 or 3 orders of magnitude.”

This could drop the price of top-tier lenses from $5000 to potentially $5 dollars per lens.

Those chunky DSLR camera lenses (and other arrays of lenses, like microscopes and telescopes) are so big because they’re made from pieces of curved glass shaped like flying saucers. The glass changes the shape of the light rays passing through it, bending them all to meet at the focus point. However, the light that passes through the edges of the glass overshoots the focus point, which makes the image blurry. The lens makers then add even more lenses to correct those so-called spherical aberrations.

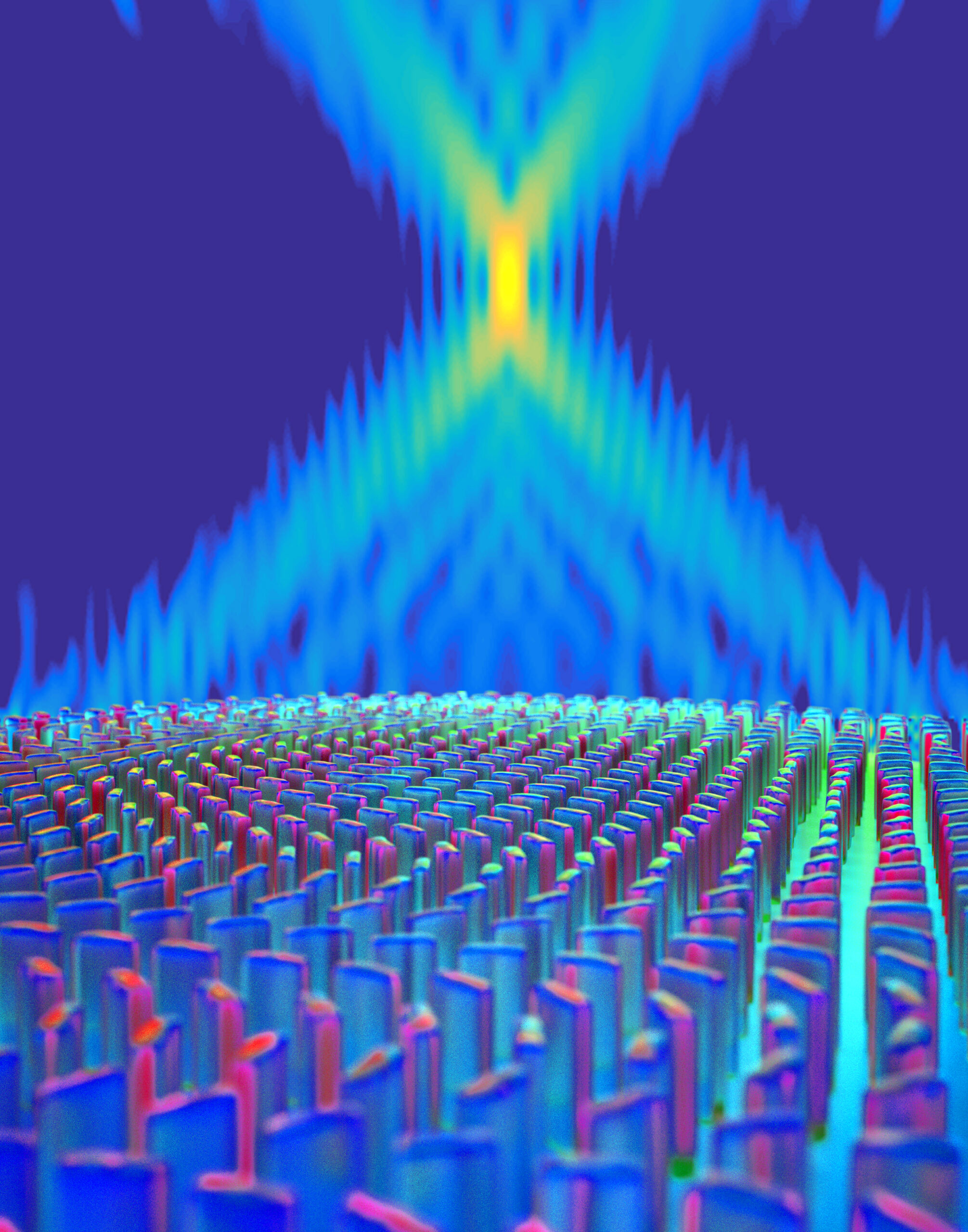

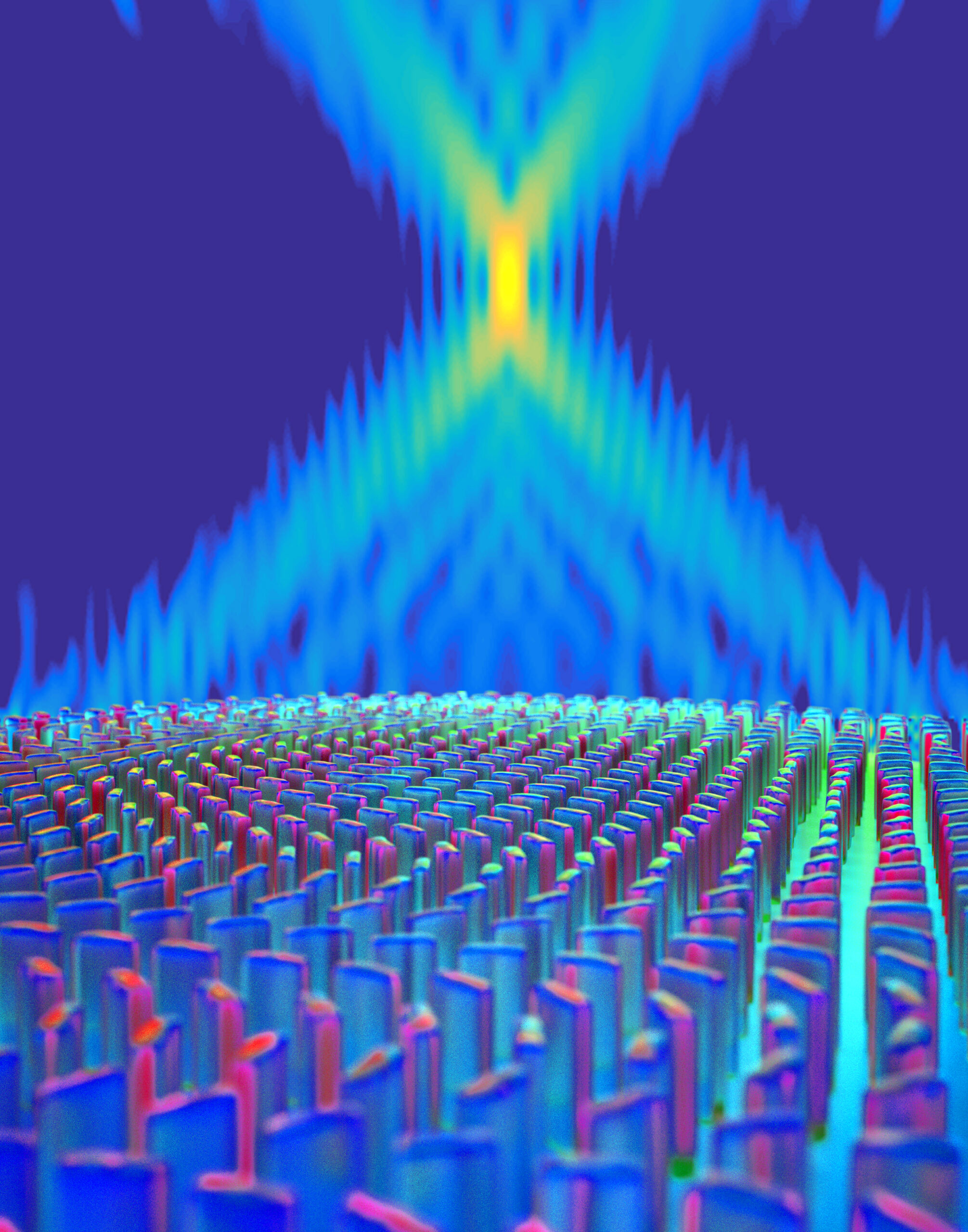

Spherical aberrations are no problem for the metalenses, which replace curved glass with flat pieces of quartz lined with an array of tiny domino-like structures made from titanium dioxide. This material is commonly found in household products like sunscreen and paint.

The domino structures are organized in a specific pattern, and each bends incoming rays of light that pass through the lens. The combined effect of all the dominoes guides and then focuses all of the incoming light rays.

There are some drawbacks. The group tested three metalenses meant for specific colors. The lenses were built to refract light at wavelengths of 405, 532, and 660 nanometers—those wavelengths correspond to purple-blue, a yellowy-green, and red. Light in other colors would make a blurry image; Khorasaninejad and his group is working on those “chromatic” or color aberrations next.

The metalenses beat a traditional lens in resolving the tiniest details, and most importantly, are almost as efficient. Not all the light that travels through a lens makes it into your camera—on the first round of testing back in 2011, only one percent of the light made it through the metalens, said Khorasaninejad. Upon their Science publication, the one metalens beat the traditional lens in efficiency, and the other two lenses tested came close.

We don’t know when we’ll end up seeing these metalenses on our iPhones, though. The size of the sensor that actually receives the light from the lens on your camera is also a crucial component in making a crisp image, and bigger sensors generally mean better pictures. Plus, as long as the lenses only work for one color of light, they’re best for use with lasers right now. But Khorasaninejad is excited to be making an impact.

“It’s science for the sake of application and making something new that can reduce the cost and increase the quality of existing systems,” he said.