Researchers at Australia’s Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) have combined brute force with high tech manufacturing to create a new silicon material for hospitals, laboratories and other potentially sensitive environments. And although it might look and feel like a flat, black mirror to humans, the thin layering actually functions as a thorny deathtrap for pathogens.

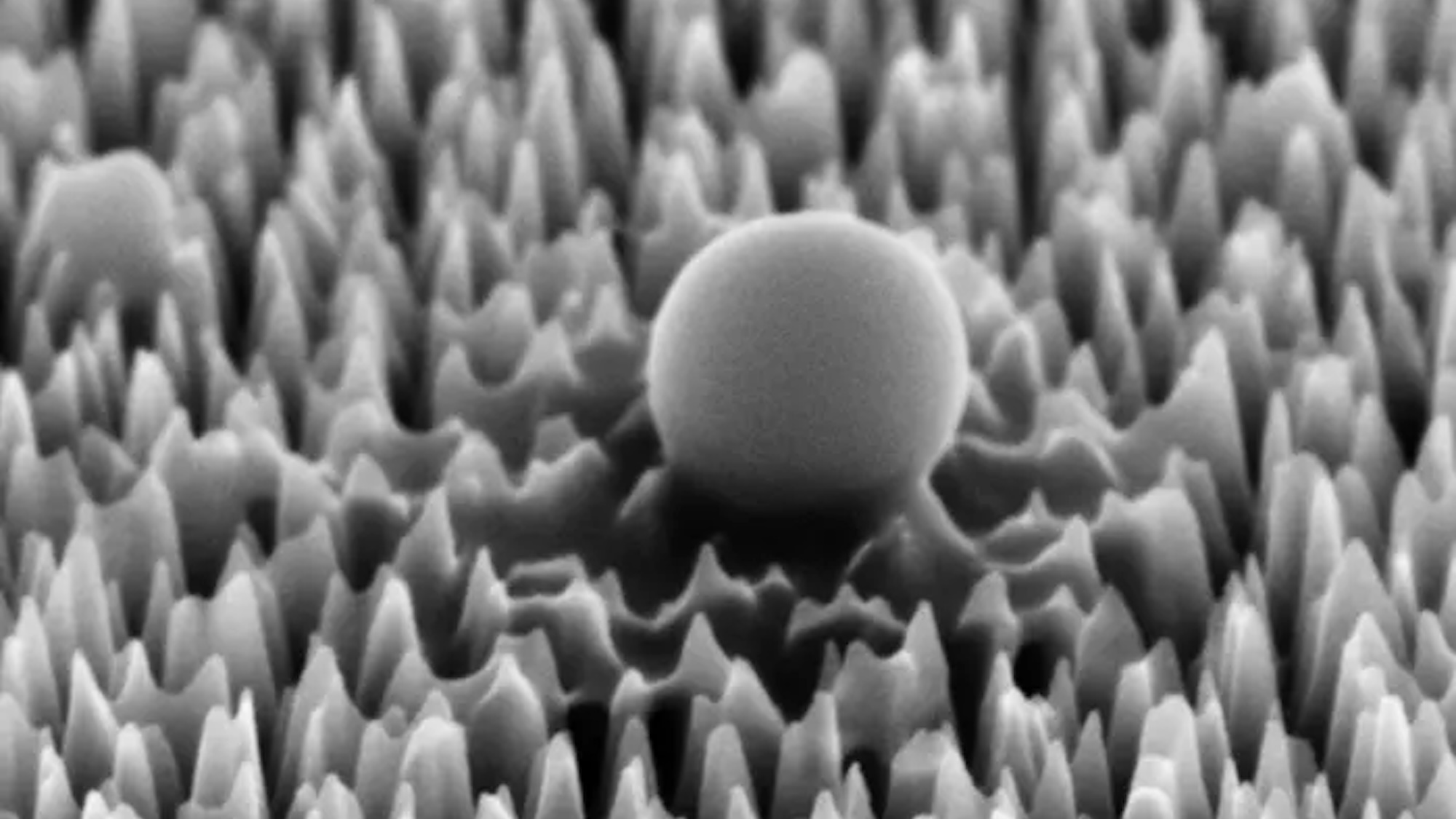

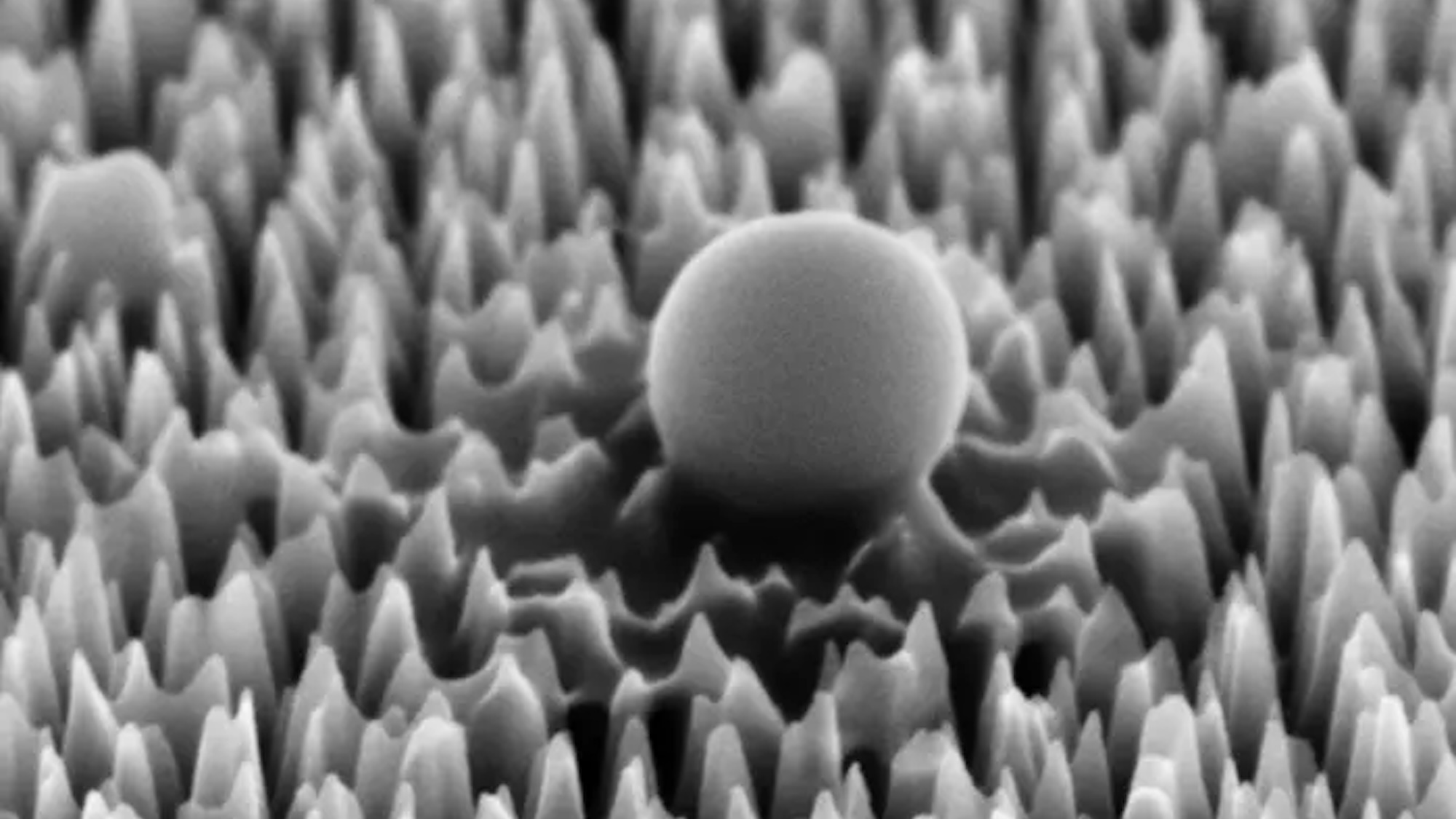

As recently detailed in the journal ACS Nano, the interdisciplinary team spent over two years developing the novel material, which is smooth to the human touch. At a microscopic level, however, the silicon surface is covered in “nanospikes” so small and sharp that they can impale individual cells. In lab tests, 96-percent of all hPIV-3 virus cells that came into contact with the material’s miniscule needles either tore apart, or came away so badly damaged that they couldn’t replicate and create their usual infections like pneumonia, croup, and bronchitis. With no external assistance, these eradication levels could be accomplished within six hours.

Interestingly, inspiration came not from vampire hunters, but from insects. Prior to designing the spiky silicon, researchers studied the structural composition of cicada and dragonfly wings, which have evolved to feature similarly sharp nanostructures capable of skewering fungal spores and bacterial cells. Viruses are far more microscopic than even bacteria, however, which meant effective spikes needed to be comparably smaller.

[Related: A once-forgotten antibiotic could be a new weapon against drug-resistant infections.]

To make such a virus-slaying surface, its designers subjected a silicon wafer to ionic bombardment using specialized equipment at the Melbourne Center for Nanofabrication. During this process, the team directed the ions to chip away at specific areas of the wafer, thus creating countless, 2-nanometer-thick, 290-nanometer tall spires. For perspective, a single spike is about 30,000 times thinner than a human hair.

Researchers believe their new silicon material could one day be applied atop commonly touched surfaces in often pathogenic-laden settings.

“Implementing this cutting-edge technology in high-risk environments like laboratories or healthcare facilities, where exposure to hazardous biological materials is a concern, could significantly bolster containment measures against infectious diseases,” Samson Mah, study first author and PhD researcher, said on Wednesday. “By doing so, we aim to create safer environments for researchers, healthcare professionals, and patients alike.”

By relying on the material’s simple, mechanical methods to effectively clean spaces (i.e., stabbing virus cells like they’re shish kabobs), the designers believe overall chemical disinfectant usage could also decrease—a major concern as society contends with the continued rise of increasingly resilient “superbugs.”