This article was originally published on The Markup.

Picture a high school student who wants to go to college, likes to cheer on her school’s football team, and plays in a sport or two herself.

One day after school, she signs up for an official ACT account so she can schedule her college entrance exam and see what score she gets after taking it. Then, she researches a few colleges through the Common App’s website, and like more than a million students every year, she uses the site to start an application for her dream college.

She spends a few minutes starting a presentation for class using the website Prezi. On a homework break, she registers for her high school’s after-school sports program through a service called ArbiterSports, then she hops on her phone, remembering to order a yearbook through the company Jostens. Long day over, she takes out her laptop and flips on her school’s big football game through the NFHS Network, a subscription service for high school sports.

Here’s what the student doesn’t know: Although she surfed the internet in the privacy of her home, Facebook saw much of what she did.

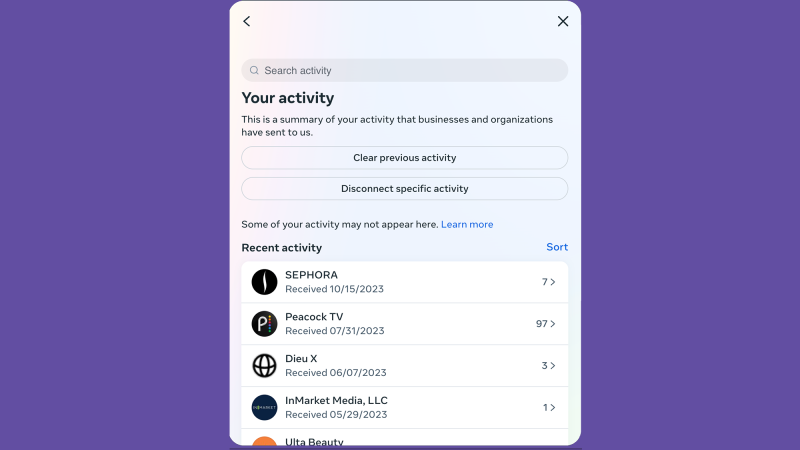

Every single site she visited used the Meta Pixel, a tracking tool that silently collects and transmits information to Facebook as users browse the web, according to testing by The Markup. Millions of invisible pixels are embedded on websites across the internet, allowing businesses and organizations to target their customers on Facebook with ads.

Businesses embed the pixel on their own websites voluntarily, to gather enough information on their customers so they can advertise to them later on Meta’s social platforms, Facebook and Instagram. If there’s a pixel on a website’s checkout page and a visitor buys a baseball hat with their school’s logo, for example, the pixel may note that interaction, and the owner of that page can send that person more apparel ads on Facebook later. This is one of the reasons people see the same ad following them on Facebook and Instagram after they shopped on a different site. The Markup has also found hospitals, telehealth companies, tax filing websites, and mental health crisis websites using the pixel, and transmitting sensitive information to social media companies.

Along with encouraging businesses to spend ad dollars, Facebook also receives the transmitted data, and can use it to hone its algorithms. Facebook can also use data from the pixel to link website visitors to their Facebook accounts, meaning businesses can reach the exact people who visited their sites. The pixel collects data regardless of whether the visitor has an account.

Our investigation found the pixel on dozens of popular websites targeting kids from kindergarten to college, including sites that students are all but required to use if they want to participate in school activities or apply to college.

See our data here: GitHub

On some level, that’s not a surprise: tracking tools like the pixel are so widespread that intensive tracking is almost the status quo. You could make the argument that these educational sites are “just the same as any other site,” said Marshini Chetty, associate professor of computer science at the University of Chicago.

But dealing with kids raises bigger questions about tracking on the web. “Why is there the Meta Pixel? Why are there session recorders?” she said. “What is the place of that on these sites?”

In 2022, around 1.4 million high school seniors took the ACT, up from 1.3 million in 2021, according to the nonprofit that runs the test. The Markup found that the official ACT sign-in page tracked users who visited the site, and when a student logged in, the pixel sent Facebook a scrambled version of the student’s email address. Meta says these “hashed” email addresses “help protect user privacy.” But it’s simple to determine the pre-obfuscated version of the data—and Meta explicitly uses the hashed information to link other pixel data to Facebook and Instagram profiles.

After signing into their ACT account, if a student accepted cookies on the following page, Facebook received details on almost everything they clicked on—including scrambled but identifiable data like their first and last name, and whether they’re registering for the ACT. The site even registered clicks about a student’s ethnicity and gender, and whether they planned to request college financial aid or needed accommodations for a disability.

An ACT spokesperson declined to comment, but a few days after The Markup reached out for comment, we tested the ACT account page for the pixel again, and found that it was no longer sending personal data to Facebook.

When students visit the Common App website, a pixel tells Facebook what they click, including whether they start an application. The associated application URL they’re directed to after doesn’t track them. More than 1 million students use the Common App to apply to colleges, according to the organization, and more than 1,000 colleges accept applications through the platform. The organization did not respond to a request for comment.

If someone starts or modifies a presentation on Prezi, Facebook gets notified. When a student or parent visits ArbiterSports to sign up for activities at their high school or college, the pixel tells Facebook what schools they searched for on the platform. When a person clicks an email address to reach out to a school for more information, the pixel tells Facebook. According to ArbiterSports’ website, the company claims to be “the backbone of K-12 and collegiate sports and event management in America” and that it’s used by “over 65 million Americans, one in every 5 of us.” Prezi and ArbiterSports didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Jostens tracks anyone looking for a yearbook in detail, telling Facebook what schools they browsed for, and sends along their hashed email address when they log in. And if a visitor navigates to a high school sports page through the NFHS network to watch a game, the site sends the text of that search to Facebook. Jostens says it partners with more than 40,000 schools and serves 2.5 million customers annually. Some schools require students to place an order with Jostens for apparel like graduation gowns. Jostens didn’t respond to a request for comment.

While many of these sites did not send along a student’s (or any website visitor’s) email or name, Facebook doesn’t need that information in order to track and retarget them for ads. Data from the pixel is connected to individual IP addresses—an identifier that’s like a computer’s mailing address and can generally be linked to a specific individual or household—creating a much more intimate connection between students and their page views. (Meta offers options on the pixel to let organizations adjust what data they collect and transmit—and here’s how you can turn it off or limit it.)

A Meta spokesperson, Emil Vazquez, noted in an emailed statement that the company has recently made changes to how advertisers can market to teens on its services, including limiting the ways advertisers can target them. The company’s terms of use for its business tools prohibit organizations from sending data on children under 13.

“We’ve been clear in our policies that advertisers should not send sensitive information about people through our Business Tools,” Vazquez said. “Doing so is against our policies and we educate advertisers on properly setting up Business tools to prevent this from occurring. Our system is designed to filter out potentially sensitive data it is able to detect.”

Tracking kids under 13

Facebook doesn’t allow children under 13 to use its services. But The Markup found that some sites directed at kids under 13 used the pixel to track visitors as well.

If a teacher assigned a class to visit the educational reading website Raz-Kids, a service for kids between kindergarten and fifth grade, for example, the site would alert Facebook when visitors clicked a button labeled “KIDS LOGIN.” (There was no pixel on a dedicated log-in page visitors are directed to after that.)

The homepages of ABC Mouse—an animated learning site—and XtraMath—an educational math service—used the tool to track visits to their homepages. The website kids.getepic.com, a digital reading platform for children, didn’t use the pixel. But if a student navigated to the main page, getepic.com, and clicked the “I’m a kid” pop-up, the click and the button text identifying them as a kid was sent to Facebook. The service explicitly markets itself on its site as being for kids 12 years old and younger.

Once a visitor gets past the homepages of these sites, however, they are no longer tracked, as the sites all have dedicated log-in pages for students that did not use the pixel tracker.

Spokespeople for these sites for kids under 13 stressed that they had separate URLs specifically for kids that did not use the pixel, and only used the pixel on their public-facing homepages to market to potential buyers of their products, like teachers.

Roy King III, Executive Director of XtraMath.org, said in an email that the site uses the pixel for business campaigns but “student data from our application is not mixed, associated, or identified with any marketing data” and that the site complies with privacy laws for children. Kiki Burger, a spokesperson for Epic, also noted their use of a separate tracking-free site and said Epic’s actual educational product does not track.

John Jorgenson, a spokesperson for Cambium Learning, parent company of Raz-Kids, similarly pointed out that kids are directed to a page without tracking, saying “our approach is to separate application log-on pages from other parts of our websites with general website traffic, which we do track.”

The Markup tested these sites for the pixel because they were some of the most commonly linked to websites from public schools in the U.S. We gathered data on popular education-related websites by building on a list created by computer science researchers from the University of Chicago and New York University (NYU) this year. The researchers used public databases of K-12 schools to develop a list of URLs for more than 60,000 public schools in the United States, generating more than 15,000 domains from those schools.

The researchers then scraped those school domains for links to other sites. They gathered a list of the links that appeared most frequently, giving them a list of which websites schools were most likely to direct visitors to. They then whittled the list down to only sites that were related to educational technology. Finally, they used The Markup’s Blacklight tool, which scans websites for trackers, finding widespread use of tools like the Meta Pixel.

The Markup re-ran the researchers’ Blacklight search, then went further. For 30 websites on the list that used the pixel, we analyzed the network traffic while browsing the site, which gave us detailed insight into how the sites communicated with Facebook.

In all, we searched through dozens of sites on the list that used the Meta Pixel in some way. The search had some limitations: Just because a school linked out to a site didn’t necessarily mean the school approved of it, or wanted students to use it. Many of those sites were also promotional sites for educational products directed toward school administrators, not students. Since they required a login, The Markup couldn’t review some of those products directly.

Jim Siegl, a senior technologist at the Future of Privacy Forum, said school districts might do a great job policing apps they contract with for services and that kids use while in school. But even trying to search for those apps through corporate marketing pages on the open web is a different story.

Siegl uses the analogy of a school in a neighborhood surrounded by a corporation, with surveillance cameras scattered all around. “In order to get to school, Billy has to walk through this corporate neighborhood and through the lobby of the corporation to get to the classroom,” he said.

Facebook’s fraught relationship with kids

Early last year, The Markup launched the Pixel Hunt, a project exploring how the Meta Pixel is quietly used to track web users. The project has highlighted several ways the Meta Pixel collects potentially sensitive data, including educational, financial, and health information. Since launch, the series has sparked concern and direct inquiry from legislators and regulators, and led to dozens of lawsuits against Meta and other companies.

However, there’s been little focus on how pixels on the web may be collecting data on kids and teens. Earlier this year, Gizmodo reported that the College Board, which is responsible for administering the SATs and Advanced Placement exams, was transmitting information on SAT scores and grades to Facebook, as well as TikTok and others. Recent testing by The Markup showed the pixel still active on some SAT-related pages. According to the College Board, 1.9 million students in the class of 2023 took the SAT. Jerome White, director of communications for the College Board, said in a statement the organization doesn’t send personally identifiable information to Meta and that “pixels are simply a means to measure the effectiveness of College Board advertising.”

Facebook’s relationship with young people is especially fraught, and comes with a years-long history of controversy that extends to today. Last month, a coalition of more than 40 states filed suit against Meta. Attorneys general for the states accused Meta of using intentionally addictive design to hook kids and teens on apps like Instagram, and violating children’s privacy in the process. Meta disputes the claims and argues that it has introduced protections for young people.

This month, Arturo Béjar, a former Facebook engineer, testified to Congress that Facebook knew about, and had failed to stop, developing systems that were hurting kids. Béjar wasn’t the first former Meta worker to weigh in on the issue. Another former employee, Frances Haugen, released internal documents in 2021 indicating Facebook knew the company’s products were damaging the mental health of teenage girls, findings that were in line with what independent researchers have said.

Those revelations followed mounting concerns that Facebook has been drawing young children into an unhealthy digital space. Those fears were magnified even further following news that Facebook planned to release a version of Instagram for children under 13 years old, who have special privacy protections in the United States.

That plan quickly led to scrutiny from lawmakers and children’s health advocates, and in 2021, about six months after news of the project leaked, the company announced that it was halting Instagram Kids. “While we stand by the need to develop this experience, we’ve decided to pause this project,” Instagram Head Adam Mosseri said in a statement at the time. “This will give us time to work with parents, experts, policymakers and regulators, to listen to their concerns, and to demonstrate the value and importance of this project for younger teens online today.”

There’s no federal privacy law in the United States that broadly covers all data. There is one law, passed in 1998, that does cover data for children under 13 years old: the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, or COPPA.

COPPA applies to sites that are directed or marketed to children under 13, or who know they’re collecting data on kids under 13. Those sites have to get parental permission before collecting data and give those families a chance to opt out, including through web tracking technologies. If not, they could face penalties from the Federal Trade Commission. Rather than face a potentially daunting task of getting parental permission from millions, some services simply don’t allow children under 13 on their platforms—although in practice, of course, many still make accounts anyway by lying about their age.

What legally counts as a service directed toward kids is open to some interpretation, with the FTC taking enforcement action against diverse companies like educational technology vendor Edmodo and Amazon, for its Alexa devices. The FTC says it might find a service is directed toward kids based on the subject matter, as well as if they feature “the use of animated characters or child-oriented activities and incentives.”

But again, “kids” means under 13. “If you’re over 13, there’s no real specific law that addresses privacy protections,” Siegl said.

In May, the FTC took direct action against Facebook, alleging the company had violated a previous privacy order and banning the company from monetizing any data collected on users under 18. The agency said Facebook’s “recklessness has put young users at risk.” Meta called the action “a political stunt” and said the FTC was stretching its authority.

There are signs that momentum is building for tighter, more expansive regulations for kids. Multiple states have proposed or passed laws that expand the types of data covered or expanded COPPA’s protections to include kids who are 13 to 18.

But attempts to pass new federal laws have stalled in the past. One now on the table, the Kids Online Safety Act, would place new requirements on social media sites to prevent minors from seeing harmful content. That bill and others have, however, triggered civil rights concerns over censorship, especially over what content might be “harmful.”

Meanwhile, the people responsible for protecting students and kids have to make do with what they have.

As part of their research, the University of Chicago and NYU team interviewed school administrators about their security practices. They broadly found that many districts lack the technical skills or resources to properly assess privacy concerns for students.

“Some sort of comprehensive federal privacy regulation would be helpful,” said Jake Chanenson, a PhD student and law student at the University of Chicago who worked on the research paper identifying educational sites. “The last privacy act we had was in the ‘90s.”

This article was originally published on The Markup and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.