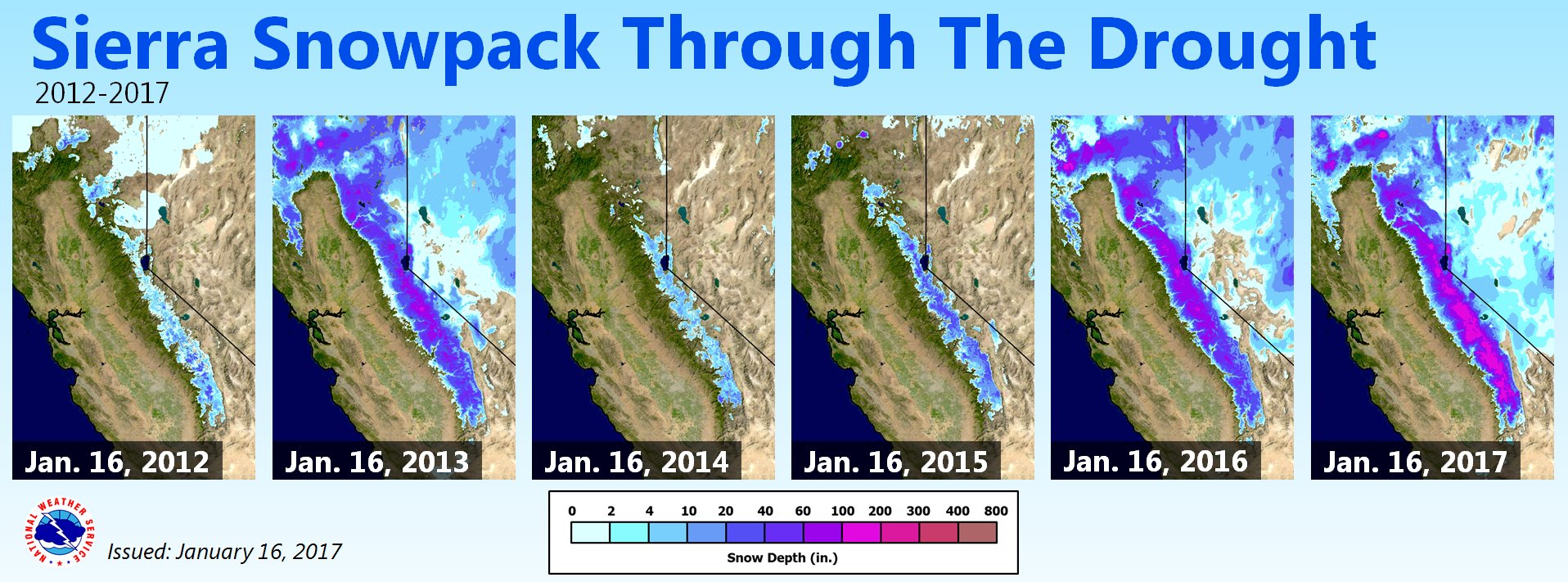

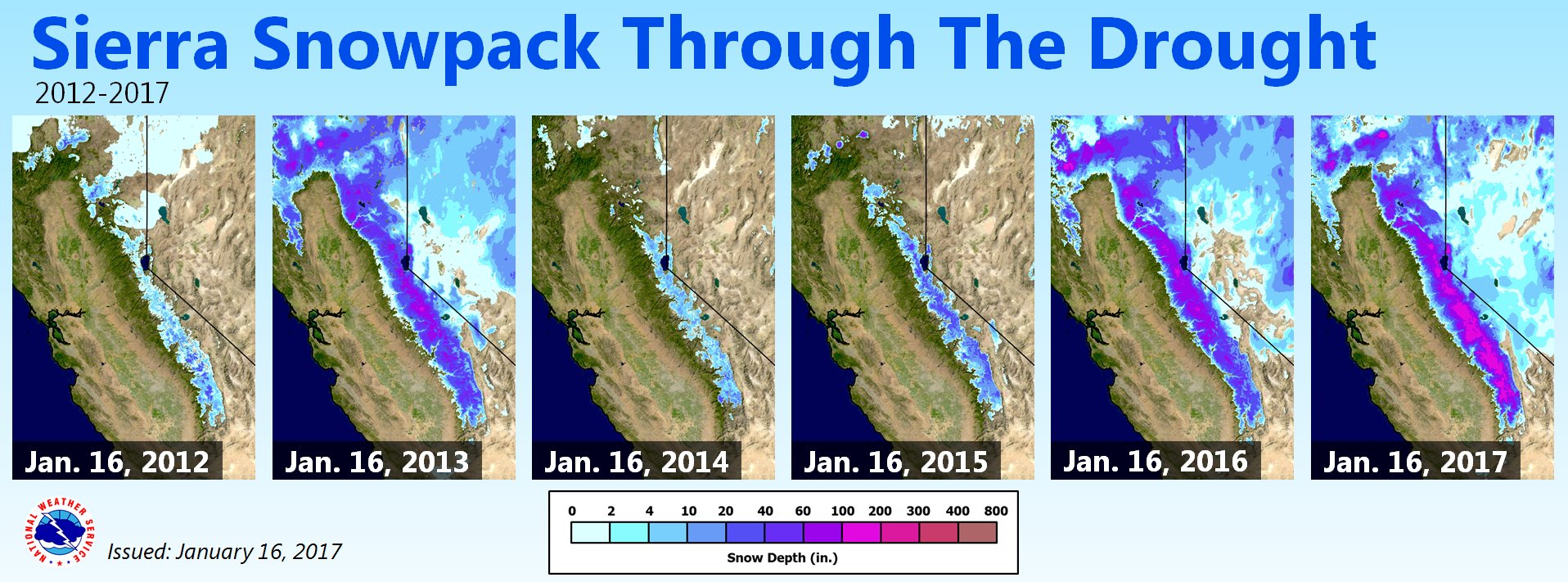

California’s wet winter continues, with rain and snowstorms still pelting the state. These constant storms are building up the California snowpack to levels that haven’t been seen in the drought-plagued state in several years.

“This is way better than some of the recent years we’ve had,” says David Pierce, a climatologist at Scripps Instituiton of Oceanography. “In the northern Sierra Nevada it’s about the same that It was last year, and that was a little above normal—so no complaints—but in the central and especially southern Sierras it’s way above where it was last year.”

The current snowpack is 163 percent above normal levels for the year, and precipitation levels in the state reached the equivalent of 80 percent of the total amount of water expected in a given California water year (water years stretch from October 1 to September 30). That’s impressive, says Pierce, but not quite record-breaking.

But even so, the snow and rain still signal a promising start to 2017. In California, a healthy snowpack isn’t just a good sign for skiiers and snowboarders. The increased snowpack could indicate a summer less water-starved than recent years. The snow stores water in the winter, and as it melts in the spring and summer it recharges rivers, increasing the water supply for farmers, cities, and the general ecosystem.

A better-than-normal snowpack means that people who rely on water (aka: everyone) can relax a little bit. But California isn’t out of the woods quite yet.

“We’re still early in the season, so we would have to get more precipitation in the state to come up to normal levels. But realistically, over the next few months that’s very likely to happen.” Pierce says.

But precipitation levels aren’t the only climate factor that Californian’s need to concern themselves with. Temperature also plays a huge role in making sure that the snowpack actually makes it through to the warmer months—when people need it the most.

“Last year in the northern and central Sierra Nevada, we reached normal amounts of snowpack, but because it was unusually warm, it melted back earlier than usual and we ended up with less snowpack than usual going into the summer.” Pierce says.

Those warmer temperatures have caused snowpack levels to dwindle a few times in recent years, Pierce says. And that’s something that will only accelerate as climate change continues to warm the world.

“A lot of the precipitation that we’ve historically gotten in the mountains has been just a little bit below the freezing temperature, and you don’t need much warming to transition that from snow to rain,” Pierce says. “Once that happens, then you lose your snowpack pretty rapidly. So by the end of this century, depending on what people do—and that’s the biggest uncertainty—we could easily lose 30 to 60 percent of our snowpack.”

That’s not the only troubling change that climate scientists expect to see. “When we get precipitation events, on average we’re likely to get more per event, but fewer events per year.” Pierce says.

Scientists also expect to see precipitation events increasingly concentrated in the winter instead of the spring. A shrinking snowpack and a change in the timing of the storms that supply California with the majority of its surface water could make the state’s current water-storage solutions even less effective.

But while researchers look ahead at a shifting water future, conditions are looking up in the short term. “At the rate we’re going now, things are looking good.” Pierce says. “Of course, if it stopped precipitating or it got crazy dry then you’d have to modify that projection, but at the moment, things are proceeding extremely well.”