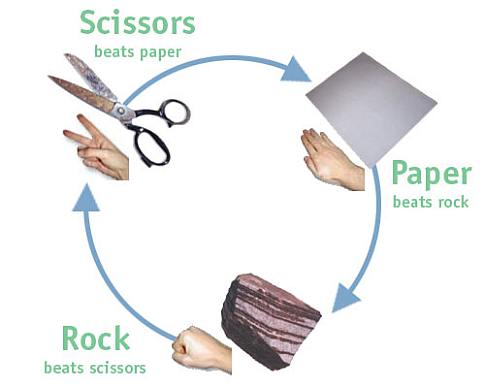

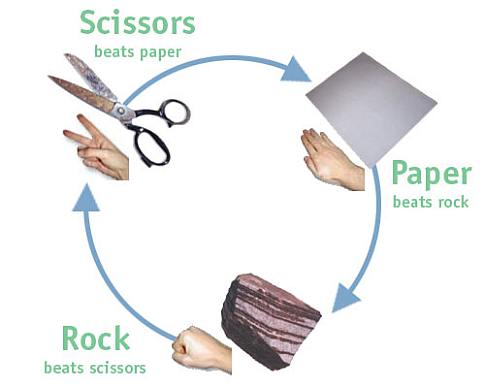

Chances are you’ve played Rock, Paper, Scissors, but how do you calculate your strategy, if you have one at all?

In Rock, Paper, Scissors: Game Theory in Everyday Life, physicist Len Fisher points out that putting yourself in your opponent’s mindset is a key to success in the game.

It’s all part of game theory, which has to do with everyday strategies and commonplace interactions — and not just those designed for winning at Monopoly or trapping wild elk, as it may sound. Fisher, a visiting research fellow in physics at the University of Bristol and author of several science books for lay audiences, argues that a teaspoon of this sort of thinking can illuminate a range of human behaviors. Not to mention that game theory offers a handy explanation of why all those teaspoons keep disappearing from the communal lunchroom at work. (Individuals think it won’t hurt the collective if they take “just one” spoon, but, voilà, in no time, there are very few, if any, left for the collective to use.)

Laura Silver recently joined Fisher by phone at his home in Blackheath, Australia to discuss his new book and, as it turned out, to play a long-distance game of Rock, Paper, Scissors. (Fisher and his wife divide their time between his home country and hers, England. And yes, they do use aspects of game theory to determine how much time to spend in each place.)

You mention that game theory touches on some of the big issues of our time, from the credit crunch and the energy crisis to how to help kids — and entire nations — share their resources. Is there one area where you think game theory can have the most profound effect?

Global warming is one of those things I think are incredibly important. If somebody’s personal interest is in politics and keeping power you have to maneuver the situation so they’re going to lose power if they don’t do something about global warming.

One of the strategies you can maneuver is that countries will lose out economically if they don’t do something. You have to maneuver around everyone’s economic interests to do something in the shorter term as well as in the longer term.

I wonder if that can work on a smaller scale, at least as it relates to stewardship. For example, I noticed a guy in Brooklyn, New York, with his dog off leash. After the dog did its business, the man picked it up with a stray piece of paper and deposited in a trash can. As soon as he walked away, the piece of paper he used blew out of the trash can. When I called it to his attention, he scowled and walked away.

Do you know where the guy lives? I’ve known some people who’ve put the result in an envelope and returned it in a letterbox.

That’s quite a coup.

It doesn’t have to be rude. If you can build on community awareness, you don’t have to have more than a moderate core of people express disapproval.

It all comes back to his future reputation being at stake. You can only build it up through a few examples: Put it in an envelope and give it back or write a letter to the local newspaper, perhaps with an identifier, “a person in a blue shirt, a person walking in this neighborhood.” That kind of thing multiplied a few times turns out to have a rather remarkable effect.

In places like Switzerland or the Scandanavian countries, if someone drops something in the street, someone is likely to pick it up and return it to them.

That idea of a community chipping in to receive a result greater than they could possibly achieve individually makes me think of open-source… as in software development and idea sharing.

It works, doesn’t it? It operates brilliantly. I think what you can take that as — what I take it as anyway — is a demonstration that people really do like to feel as if they’re part of a cooperative community, that people aren’t totally all take and no give. People like to give so long as others give as well. When others stop giving, then the whole system falls apart.

Is there a tie-in between open source systems and game theory?

This just shows the strength of the giving feeling in individuals. Giving is one of the strongest drives. We like to be part of a family. We like to be part of a community. You can still argue that it’s self-interest. Somehow you’ve got to serve people’s self interests. But one of the big ones is an interest in feeling that you’re part of a community.

And if you can lock into that, then you’re giving them the reward for being part of a community. And that’s their reward for cooperating. It’s one of the biggest rewards we have.

It’s a pity that the politicians just don’t seem to have that feeling quite that strong, isn’t it?

I’m always struck by examples of everyday people, especially those outside of the Western world. When I was in Senegal, I was shocked when a ten-year-old girl refused to open a package of snacks until she could share them with her extended family. It didn’t even occur to her to keep the whole thing for herself or to sample one before being with the group.

That is brilliant. We seem to have lost that a lot in Western countries. Maybe one of the things we should be doing is to rework our culture, to change the thought of ‘reward’ would really get people cooperating. It’s as much of a reward to share.

On the other end of the spectrum, I’m also interested in your take on the Madoff scandal, in light of your recent article. The investors are to a large extent being portrayed as victims.

I’ve got to be very careful with my wording of that…. I’d reckon that a substantial proportion had a very, very good idea of what was going on. But they thought they were gaining an advantage, so no one cared to look closely.

Do you ever find that in your own life? You think you’ve gotten away with something, but you don’t really want to know… in case it turns out that it was really illegal, what happened or rather bad in some other point of view.

Yes, of course. Do you have any examples of that from your own life, by chance?

I’m just trying to think of a publishable one…

I’ll tell you what happened a few weeks ago with me. No one will ever know the names in America, so it won’t matter too much. We’re very fond of garage sales. We’ve basically furnished the whole house from garage sales. Of course, occasionally at a garage sale, people are going to be selling stuff that’s not theirs. We went to one where this guy had a whole heap of stuff for the workshop, including some wonderful high-tensile bolts.

Then he pointed out as I was taking them, that these bolts weren’t an awful lot of money, because they were airplane bolts. And he also gave me his card, which I didn’t look at until later. At the bottom of the card it said ‘firearms dealer.’ And his title was Colonel someone or other. And you can just bet that he came by this stuff, sort of ‘fell off the back of the truck’ when he was working for the army or the air force. But I already got my bargain. There’s no way I can give it back to whoever it belongs to. So I’m OK, I don’t have too bad a conscience.

I came not choosing to know who this guy was, when I just saw he had high-tensile bolts. I didn’t inquire too closely. I just bought the bolts. So I’m a naughty boy as well.

Maybe not on the same scale.

I hope not.

How many did you buy?

Probably quite a few hundred. Enough for an airplane to fall out of the sky, I think.

And how many games of Rock, Paper, Scissors have you played?

Very few. I find that I can always win now, when people challenge me to it. So if they haven’t read the book, I just play paper, because they play rock.

If they have read the book, I just play scissors, because they play paper. I hardly ever lose. That is the classic game theory, actually. Game theory started on this idea that you try to put yourself in the other person’s head and think for them, ‘What’s they’re best strategy going to be?’ And you assume they’re going to use their best strategy.

Then and only then do you start thinking about your own strategy. If the other person knows as much about game theory as you do, that’s when you can do better by being unpredictable, by being random.

The best thing you can do in Rock, Paper, Scissors is to randomize the throws.

Well, I’m sorry we can’t play a game in person.

Do you want to play one now?

[Listen to the game]

Anything else you’d like to add?

I just think it’s so important for people to be aware of the ideas of game theory, especially being aware of the Tragedy of the Commons, and how it arises…

That notion of individuals all taking spoons from the common cafeteria, each thinking their appropriation of a single spoon won’t effect others…

If you’re cooperating with someone and one of you cheats, you can get away with it. But when you both cheat, you do worse than if you kept on cooperating.

It’s this huge trap that underlies most of the problems we run into and it never gets mentioned. Never gets mentioned at all. If you read books on the credit crunch, some of the major ones, you look in the index, and you won’t even find game theory mentioned. It’s crucial to what’s going on. Game theory belongs to everyone, not just the specialists.

And if anyone can come up with a better name than game theory, God, wouldn’t that be good. Something that really grabs you.

Do you have any ideas?

If I had, that would have been the title. If anyone has an idea, put it on my blog; they’ll get an acknowledgment.

For a chance to win one of five copies of Rock, Paper, Scissors_, post a comment (any comment) below, by January 31st, 2009_