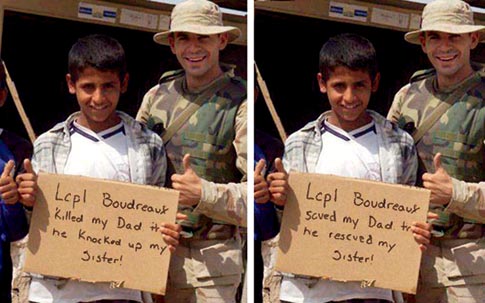

Lance Corporal Ted “JOEY” Boudreaux Jr. was bored. It was the summer of 2003 in Iraq, the pause between the heavy lifting of the U.S. invasion and the turmoil of the insurgency, and you can joyride around the desert in a dusty Humvee only so often. Loitering at the back gate of his base, mingling with locals, Boudreaux says he scribbled “Welcome Marines” on a piece of cardboard and gave it to some kids, who then posed with him, smiling, for a snapshot. He e-mailed the picture to his mom, a cousin and a few friends, and he didn´t think about it again. Boredom moved on. That wasn´t the last of the photo, though. The image made its way to the Internet and fell into the hands of bloggers-Boudreaux says he doesn´t know how-except that the sign had been altered to say, “Lcpl Boudreaux killed my dad, then he knocked up my sister.” Online commentators assumed Boudreaux was playing a nasty trick on kids who couldn´t read English, and the Marine was flamed as insensitive, ignorant or just plain stupid. The Council on American-Islamic Relations stumbled across the image and demanded an inquiry.

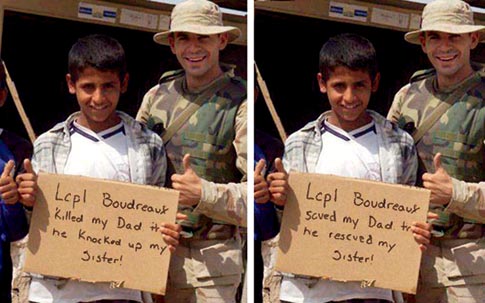

Around the same time, another image popped up on the forums of the conservative Web site freerepublic.com. Now the sign read “Lcpl Boudreaux saved my dad, then he rescued my sister,” and a debate raged. Other versions of the sign appeared-one was completely blank, apparently to show how easily a photo can be doctored, and another said “My dad blew himself up on a suicide bombing and all I got was this lousy sign.” By this point, Boudreaux, 25, was back in his hometown of Houma, Louisiana, after his Iraq tour, and he found out about the tempest only when a fledgling Marine brought a printout of the “killed my dad” picture to the local recruiters´ office where Boudreaux was serving. Soon after, he learned he was being investigated by the Pentagon. He feared court-martial. It would be months before he would learn his fate.

Falling victim to a digital prank and having it propagate over the Internet may seem about as likely as getting struck by lightning, but in the digital age, anyone can use inexpensive software to touch up photos, and their handiwork is becoming increasingly difficult to detect. Most of these fakes tend to be harmless-90-pound housecats, sharks attacking helicopters, that sort of thing. But hoaxes, when convincing, can do harm. During the 2004 presidential election campaign, a potentially damning image proliferated on the Internet of a young John Kerry sharing a speaker´s platform with Jane Fonda during her “Hanoi Jane” period. The photo was eventually revealed to be a deft composite of two images, but who knows how many minds had turned against Kerry by then. Meanwhile, politicians have begun to engage in photo tampering for their own ends: This July it emerged that a New York City mayoral candidate, C. Virginia Fields, had added two Asian faces to a promotional photograph to make a group of her supporters seem more diverse.

“Everyone is buying low-cost, high-quality digital cameras, everyone has a Web site, everyone has e-mail, Photoshop is easier to use; 2004 was the first year sales of digital cameras outpaced traditional film cameras,” says Hany Farid, a Dartmouth College computer scientist and a leading researcher in the nascent realm of digital forensics. “Consequently, there are more and more cases of high-profile digital tampering. Seeing is no longer believing. Actually, what you see is largely irrelevant.”

That´s a problem when you consider that driver´s licenses, security cameras, employee IDs and other digital images are a linchpin of communication and a foundation of proof. The fact that they can be easily altered is a big deal-but even more troubling, perhaps, is the fact that few people are aware of the problem and fewer still are addressing it.

It won´t be long-if it hasn´t happened already-before every image becomes potentially suspect. False images have the potential to linger in the public´s consciousness, even if they are ultimately discredited. And just as disturbingly, as fakes proliferate, real evidence, such as the photos of abuse at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, could be discounted as unreliable.

And then there´s the judicial system, in which altered photos could harm the innocent, free the guilty, or simply cause havoc. People arrested for possession of child pornography now sometimes claim that the images are not of real children but of computer-generated ones-and thus that no kids were harmed in the making of the pornography (reality check: authorities say CG child porn does not exist). In a recent civil case in Pennsylvania, plaintiff Mike Soncini tussled with his insurance company over a wrecked vehicle, claiming that the company had altered digital photos to imply that the car was damaged before the accident so as to avoid paying the full amount due. In Connecticut, a convicted murderer appealed to the state supreme court that computer-enhanced images of bite marks on the victim that were used to match his teeth were inadmissible (his appeal was rejected). And in a Massachusetts case, a police officer has been accused of stealing drugs and money from his department´s evidence room and stashing them at home. His wife, who has accused him of spousal abuse, photographed the evidence and then confronted the cop, who allegedly destroyed the stolen goods. Now the only evidence that exists are digital pictures shot by someone who might have a motive for revenge. “This is an issue that´s waiting to explode,” says Richard Sherwin, a professor at New York Law School, “and it hasn´t gotten the visibility in the legal community that it deserves.”

So far, only a handful of researchers have devoted themselves to the science of digital forensics. Nevertheless, effective, if not foolproof, techniques to spot hoaxes are emerging-and advances are on the horizon. Scientists are developing software, secure cameras and embedded watermarks to thwart image manipulation and sniff out tampering. Adobe and Microsoft are among the private funders, but much of the work is seeded by law-enforcement agencies and the military, which face situations in which more than just reputations are at risk. (Maintaining the integrity of the chain of evidence is of utmost importance to law enforcement, and the military is concerned about the veracity of images arriving from, say, Iraq or Afghanistan. Does that picture really portray Osama bin Laden? Are those hostages in the grainy video really American soldiers?)

But Farid and other experts are concerned that they´ll never win. The technologies that enable photo manipulation will grow as fast as the attempts to foil them-as will forgers´ skills. The only realistic goal, Farid believes, is to keep prevention and detection techniques sophisticated enough to stop all but the most determined and skillful. “We´re going to make it so the average schmo can´t do it,” he says.

Faked photography has a long and inglorious history. In the 1870s, “spirit photographs” were the rage-images of dead loved ones were combined with shots of living kin taken during sances and passed off by charlatans as proof of the spirit world. During the Cold War, the Russian and Chinese governments were notorious for their propaganda fakes; discredited officials were routinely removed from state photographs. But the human eye isn´t easily fooled: Hardwired for pattern recognition, people can readily spot subtle inconsistencies. Verification experts look for these anomalies-differences in light, shadow and shading; perspective that´s out of whack; and incorrect proportions, such as one person´s head being unnaturally larger than another´s. Thanks to the digital nature of today´s photos, though, never has it been so easy to fool the eye with high-quality forgeries, reshaping reality with a few clicks of a mouse. A digital camera contains a light-sensitive plate covered with tiny sensors called cells, which receive photons of light when the shutter opens. The cells collect photons like raindrops in buckets, then convert them into electrical charges, which are amplified and themselves converted from analog to digital form. In every digital image format-JPEG, TIFF, RAW-a photograph is really just a data file consisting of strings of zeros and ones. A program is required to translate that binary code into pictures, much the way your TV converts digital cable or satellite signals into moving images.

Such programs abound. Five million copies of Adobe Photoshop have been licensed, iPhoto is bundled with all new Apple computers, and Picasa 2 is available free from Google. This software not only interprets the original data; it´s capable of altering it-to remove unwanted background elements, zoom in on the desired part of an image, adjust color, and more. And the capabilities are increasing. The latest version of Photoshop, CS2, includes a “vanishing point” tool, for example, that drastically simplifies the specialized art of correcting perspective when combining images, to make composites look more realistic. Nor are these programs difficult to master. Just as word-processing programs like Microsoft Word have made the production of professional-looking documents a cakewalk, photo-editing tools make us all accomplished photo manipulators fairly quickly. Who hasn´t removed red-eye from family pictures?

Before the digital age, photo-verification experts sought to examine the negative-the single source of all existing prints. Today´s equivalent of a negative is the RAW file. RAWs are output from a camera before any automatic adjustments have corrected hue and tone. They fix the image in its purest, unaltered state. But RAW files are unwieldy-they don´t look very good and are memory hogs-hence only professional photographers tend to use them. Nor are they utterly trustworthy: Hackers have shown themselves capable of making a fake RAW file based on an existing photo, creating an apparent original.

But digital technology does provide clues that experts can exploit to identify the fakery. In most cameras, each cell registers just one color-red, green or blue-so the camera´s microprocessor has to estimate the proper color based on the colors of neighboring cells, filling in the blanks through a process called interpolation. Interpolation creates a predictable pattern, a correlation among data points that is potentially recognizable, not by the naked eye but by pattern-recognition software programs.

Farid has developed algorithms that are remarkably adept at recognizing the telltale signs of forgeries. His software scans patterns in a data file´s binary code, looking for the disruptions that indicate that an image has been altered. Farid, who has become the go-to guy in digital forensics, spends a great deal of time using Photoshop to create forgeries and composites and then studying their underlying data. What he´s found is that most manipulations leave a statistical trail.

Consider what happens when you double the size of an image in Photoshop. You start with a 100-by-100-pixel image and enlarge it to 200 by 200. Photoshop must create new pixels to make the image bigger; it does this through interpolation (this is the second interpolation, after the one done by the camera´s processor when the photo was originally shot). Photoshop will “look” at a white pixel and an adjoining black pixel and decide that the best option for the new pixel that´s being inserted between them is gray.

Each type of alteration done in Photoshop or iPhoto creates a specific statistical relic in the file that will show up again and again. Resizing an image, as described above, creates one kind of data pattern. Cutting parts of one picture and placing them into another picture creates another. Rotating a photo leaves a unique footprint, as does “cloning” one part of a picture and reproducing it elsewhere in the image. And computer-generated images, which can look strikingly realistic, have their own statistical patterns that are entirely different from those of images created by a camera. None of these patterns is visible to the naked eye or even easily described, but after studying thousands of manipulated images, Farid and his students have made a Rosetta stone for their recognition, a single software package consisting of algorithms that search for seven types of photo alteration, each with its own data pattern.

If you employed just one of these algorithms, a fake would be relatively easy to miss, says digital-forensic scientist Jessica Fridrich of the State University of New York at Binghamton. But the combination is powerful. “It would be very difficult to have a forgery that gets through all those tests,” she says.

The weakness of Farid´s software, though-and it´s a big one-is that it works best with high-quality, uncompressed images. Most nonprofessional cameras output data files known as JPEGs. JPEGs are digitally compressed so that they will

be easy to e-mail and won´t take up too much space on people´s hard drives. But compression, which throws away less-

important image data to reduce size at the expense of visual quality, removes or damages the statistical patterns that Farid´s algorithms seek. So at least for now, until Farid´s next-generation software is finished, his tool is relatively powerless to

provide information about the compressed and lower-quality photos typically found on the Internet.

Given those rather large blind spots, some scientists are taking a completely different tack. Rather than try to discern after the fact whether a picture has been altered, they want to invisibly mark photos in the moment of their creation so that any subsequent tampering will be obvious.

Jessica Fridrich of SUNY Binghamton works on making digital watermarks. Watermarked data are patterns of zeros and ones that are created when an image is shot and embedded in its pixels, invisible unless you look for them with special software. Watermarks are the modern equivalent of dripping sealing wax on a letter-if an image is altered, the watermark will be “broken” digitally, and your software will tell you.

Watermarking is currently available in one consumer product, Canon´s DVK-E2 data-verification kit. This $700 system uses proprietary software and a small USB plug-in application to authenticate images shot with Canon´s pro-level cameras. It would seem ideal for news organizations: Photo editors (or anyone needing to authenticate) plug in the device, click on an image, and the software alerts them when a photo has been altered. Most digital news photos will be tweaked, of course, to adjust hue, saturation, contrast and brightness-editing procedures that were traditionally conducted in the darkroom-and then saved as a new file, but if the editor suspects funny business, he can compare the unaltered original with the altered copy and find out exactly how much it deviates.

The Canon kit won´t prevent self-made controversies, such as National Geographic´s digitally relocating an Egyptian pyramid to fit better on its February 1982 cover, or Newsweek´s grafting Martha Stewart´s head onto a model´s body on its March 7, 2005, cover, but it would have caught, and thus averted, another journalism scandal: In 2003 photographer Brian Walski was fired from the Los Angeles Times for melding two photographs to create what he felt was a more powerful composition of a British soldier directing Iraqis to take cover. Still, many media outlets remain dismissive of verification technology, putting their faith in the integrity of trusted contributors and their own ability to sniff out fraud. “If we tried to verify every picture, we´d never get anything done,” says Stokes Young, managing editor at Corbis, which licenses stock photos. As damaging mistakes pile up, though, wire services and newspapers may change their attitude.

Meanwhile, work is progressing at Fridrich´s lab to endow photos with an additional level of security. Fridrich, whose accomplishments include winning the 1982 Czechoslovakian Rubik´s Cube speed-solving championship, is developing a camera that not only watermarks a photograph but adds key identifying information about the photographer as well. Her team has modified a commercially available Canon camera, converting the infrared focusing sensor built into its viewfinder to a biometric sensor that captures an image of the photographer´s iris at the instant a photo is shot. This image is converted to digital data that is stored invisibly in the image file, along with the time and date and other watermark data.

The application for a police photographer is obvious: If challenged in court, the image, camera and shoot are verifiable, the entire system secure. Unfortunately, the world of justice is the Dark Ages to academia´s Renaissance. The FBI has a special Digital Evidence Section and is funding authentication research, but federal rules of evidence don´t require verification of digital images other than by the photographer or someone else at the scene, let alone a secure photography system, and there´s been little effort to change them. “Most criminal courts are technically illiterate,” says Grant Fredericks, a forensic-video analyst with forensic-systems maker Avid Technology. “They don´t have the tools and experience to deal with advanced technology.”

Lawyers are just beginning to grasp the technology and its ramifications, but the bench is especially ignorant. “Trial judges have not been adequately apprised of the risks and technology,” says New York Law School´s Sherwin. “I can recount one example where in order to test an animation that was being offered in evidence, the judge asked the attorney to print it out. What we really have is a generation gap in the knowledge base. Courts are going to have to learn about these risks themselves and find ways to address them.”

One bright spot is that for now, at least, we only have to worry about still images. Fredericks says that to modify video convincingly remains an incredibly painstaking business. “When you´re dealing with videotape, you´re dealing with 30 frames per second, and a frame is two individual pictures. The forger would have to make 60 image corrections for each second. It´s an almost impossible task.” There´s no Photoshop for movies, and even video altered with high-end equipment, such as commercials employing reanimated dead actors, isn´t especially believable.

Digital-forensics experts say they´re in an evolutionary race not unlike the battle between spammers and anti-spammers -you can create all the filters you want, but determined spammers will figure out how to get through. Then it´s time to create new filters. Farid expects the same of forgers. With enough resources and determination, a forger will break a watermark, reverse-engineer a RAW file, and create a seamless fake that eludes the software. The trick, Farid says, is continuing to raise the bar high enough that most forgers are daunted.

The near future of detection technology is more of the same, only (knock wood) better: more-secure photographer-verification systems, more tightly calibrated algorithms, more-robust watermarks. The future, though, promises something more innovative: digital ballistics. Just as bullets can be traced to the gun that fired them, digital photos might reveal the camera that made them. No light sensor is flawless; all have tiny imperfections that can be read in the image data. Study those glitches enough, and you recognize patterns-patterns that can be detected with software.

Still, no matter what technologies are in place, it´s likely that top-quality fakes will always elude the system. Poor-quality ones, too. The big fish learn how to avoid the net; the smallest ones slip through it. Low-resolution fakes are more detectable by Farid´s latest algorithm, which analyzes the direction of light falling on the scene, but if a photo is compressed enough, forget about it. It becomes a mighty small fish.

Which brings us back to Joey Boudreaux, the Marine who found himself denounced by his local paper, the New Orleans Times-Picayune, as having embarrassed “himself, the Marine Corps and, unfortunately, his home state.” The Marines conducted two investigations last year, both of which were inconclusive. Even experts with the Naval Criminal Investigative Services couldn´t find evidence to support or refute claims of manipulation.

Boudreaux has taken the incident in stride. “My first reaction, I thought it was funny,” he said in a telephone interview. “I didn´t have a second reaction until they called and said, â€You´re getting investigated.´ ” He insists that he never gave the Iraqi boy a sign with any words but “Welcome Marines,” but he has no way to prove it. Neither he nor anyone he knows still possesses a version of the image the way he says he created it, and no amount of Internet searching has turned it up. All that exists are the low-quality clones on the Web. Farid´s software can´t assess Boudreaux´s claim because the existing images are too compressed for his algorithms. And even Farid´s trained eye can´t tell if either of the two existing images-the “good” sign or the “bad” one-are real or if, as Boudreaux claims, both are fakes.

An unsatisfactory conclusion, but a fitting one. Today´s authentication technology is such that even after scrutiny by software and expert eyes, all you may have on your side is your word. You´d better hope it´s good enough.

Steve Casimiro is a writer and photographer in Monarch Beach, California.