Vital to reproduction, poorly understood, and on the menu since the 1970s—these are all ways to describe the mighty human placenta. The pancake-shaped organ forms during pregnancy to connect a fetus to the uterus around it. It then works with the umbilical cord to bring nutrients, hormones, and oxygen to the growing baby while also removing its waste. Research has shown that placental problems can indicate health issues in both the fetus and the pregnant person, from gestational diabetes and preeclampsia to stillbirth and premature delivery.

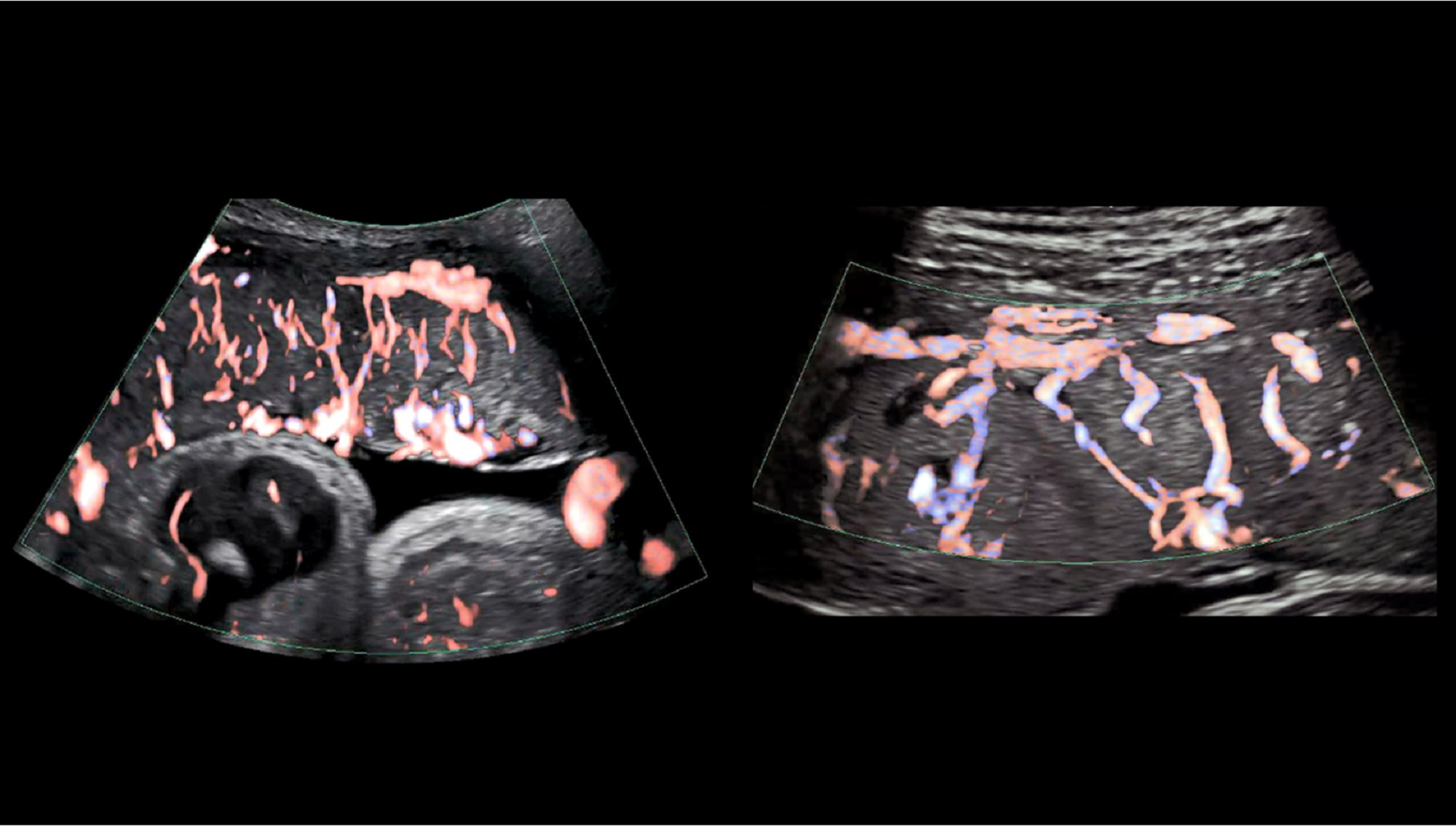

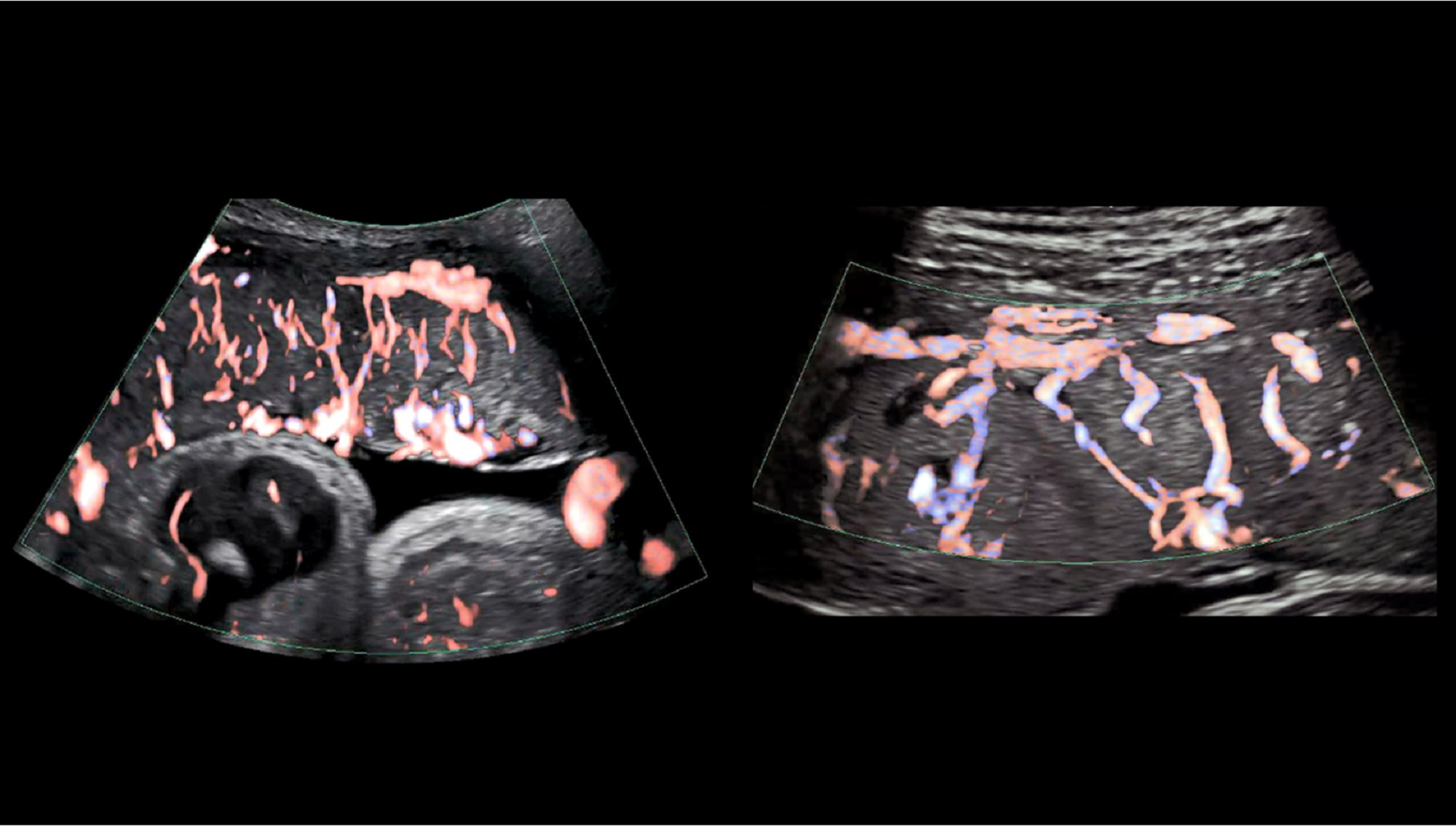

But beyond the essentials, experts know very little about how the placenta develops and operates. In a recent blog post, Diana W. Bianchi, a senior investigator at the National Institute of Health (NIH), wrote that the placenta is “the least understood, and least studied organ.” She then explains how developing better ultrasound and MRI imaging techniques can help doctors study the placenta during pregnancy, work that the Eastern Virginia Medical School and University of Texas Medical Branch have used to study placental vasculature, as shown above.

[Related: Miscarriages could become more dangerous in a post-Roe world]

So, what’s with all the mystery around an organ that has such a major role in the birthing process? “The placenta is almost not accessible until the end of the pregnancy when the baby is delivered. Then it is basically discarded,” Hemant Suryawanshi, assistant professor of reproductive sciences at Columbia University, says. “Most of our knowledge about the placenta is from the last trimester when the pregnancy is done, but that is the stage where the pregnancy is already completed.”

“What is crucial about the placenta is its early stage of development, where it is dynamically modifying its number of cells, the cell states, and how it interacts with the mother’s tissue versus the fetus tissue,” he adds.

To better understand the placenta in utero, the NIH created the Human Placenta Project (HPP) in 2014. Since then, nearly $88 million has been dedicated to develop better research techniques to study the organ in real time. On his end, Suryawanshi has completed two projects with the HPP, starting with a 2018 survey of first-trimester placenta cells. His team also sequenced RNA from newly developed placentas to begin building a genomic map; his recently published paper continued the research by mapping placenta RNA across all three trimesters of pregnancy.

[Related: What we might learn about embryos and evolution from the most complete human genome map yet]

“Our aim was to just see what exists in ‘a normal condition’ at single cell level and also across the different trimesters,” Suryawanshi says. “For example, preeclampsia or placenta accreta are diseases where the placenta is specifically involved. If you take those tissues from the disease conditions and profile their RNA, we have nothing to compare it to—there is no blueprint, and there is no profile already available.”

Suryawanshi’s research has coincided with other HPP projects that focus on everything from sourcing the placental microbiome to investigating the organ’s genetic response to environmental pollution. But overall, one of the NIH initiative’s central goals is to better address health issues related to the placenta—something Suryawanshi thinks will require a lot more research. In the future, he hopes to investigate disease conditions on a single-cell level similar to the placenta genome map his team has already worked on, and even analyze fetal cells within a pregnant person’s blood.

Correction (June 9, 2022): Hemant Suryawanshi’s last name was originally misspelled. The story has been updated with the correct spelling.